We marked last month’s fifth anniversary of the imposition of lockdown on the British people by republishing some of our articles from that week. While the mainstream media were baying for stronger and longer restrictions, we were almost alone in criticising lockdown and showing that it would have catastrophic results for zero benefit. We continue to remind readers of the weeks – and the insane policies imposed on us – that followed. This article was published five years ago today, on April 15, 2020, under the heading ‘Was this catastrophic lockdown ever needed?’

LOCKDOWNS around Europe are beginning to be loosened. Small shops in Austria and the Czech Republic and schools in Denmark are reopening this week, while Norway’s schools reopen next week.

The UK had the opportunity here to get ahead of the curve for the first time and reopen Britain for business, as John Redwood MP urged when he wrote to Cabinet members on Monday. With unemployment through the roof and rising by the day, there is no time to lose.

But the decision has been taken to keep Britain in lockdown for another three weeks as the Cabinet continues to debate whether it should be eased. This is potentially disastrous – especially if it turns out that the lockdown has been of limited value in containing the virus.

In my last post I suggested that evidence from Gangelt in Germany, Shenzhen in China and the Diamond Princess cruise ship, plus the low proportion of tests (ten per cent) coming out positive in Germany (we could also add America to that) indicate that the Wuhan coronavirus might, for reasons not yet understood, infect only 15 to 20 per cent of a population (regardless of lockdown measures), at least in this wave.

If this is the case, then the projections of deaths from the virus are hugely overestimated. The idea of aiming for ‘herd immunity’ through 60 per cent of the population becoming infected is also misguided, as it will take a very long time to reach that figure, and besides it appears that we will achieve some kind of herd immunity much sooner.

But even if this is incorrect, and despite early indications the virus will eventually spread to almost the entire population, we still need to end the lockdown as a matter of urgency, while taking measures to help protect the most vulnerable that have so far been widely ignored – such as protective equipment, flu vaccination and testing for care home workers.

The lockdown itself is having a serious impact on health in other ways, such as pushing out ordinary patients from the health service and isolating people at risk, possibly resulting in up to 150,000 additional deaths according to one government model.

Matt Hancock, the Health Secretary, has now said the NHS has 2,295 spare critical care beds (compared to 800 in normal times), so should be well prepared for new outbreaks.

The Covid-19 death rate also increasingly appears to be much lower than the originally predicted 3.4 per cent from the World Health Organisation or 0.9 per cent from Imperial College. A new Danish antibody study with 1,500 blood donors found a death rate of 0.16 per cent, similar to flu. Another antibody study from Colorado, USA, came to a similar conclusion. The study in Gangelt, mentioned above, found 0.37 per cent. These represent death tolls that are much more comparable to flu epidemics.

With UK deaths with (not from) Covid-19 now standing at 11,329 (on April 13) and estimated to finish up around 20,000, this figure at the momentis somewhat less than the 28,330 who died in the flu epidemic of 2014-2015. The latest overall mortality figures for the UK show a spike (which may be revised) that is still well below the 2015 spike/

While it has not yet (as of April 5) turned downwards, given that Covid-19-related deaths appear to be peaking, it should do very soon, meaning 2020 may end up looking similar to 2015 in terms of excess deaths. But in any case, should the outbreak look to be getting out of control, targeted restrictions could be reintroduced.

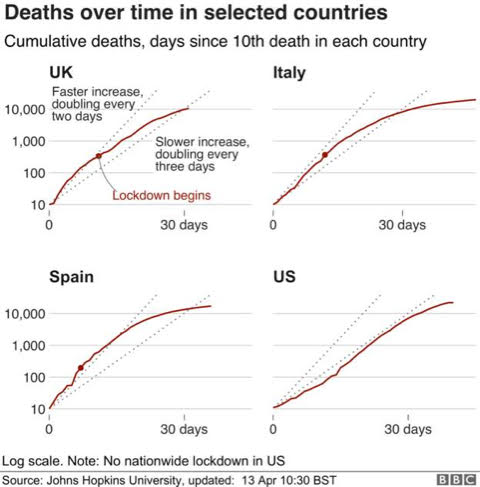

This is assuming, of course, that lockdowns achieve very much at all and the recent ‘flattening of the peak’ does reflect its efficacy. The graphs below show the reported deaths in four badly-affected countries as they add up over time, with the date of lockdown indicated on each.

The BBC reporter comments that ‘slowing infection rates are raising hopes that strict social distancing measures are curbing the spread of the coronavirus.’ But isn’t the most noticeable thing about the graphs how little effect the lockdown seems to have on the shape of the curve?

The UK death rate is already slowing on this graph before the lockdown, while in Spain the death rate seems to slow as soon as the lockdown is imposed, which is far too soon – it would take around two weeks for the effect to show up in the deaths.

In the US, the curve plateaus in a similar place to the others (actually, given the much larger population of the US, the plateau is, proportionally, far lower) despite there being no national lockdown and varied measures in different states.

Source: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-51235105

The effectiveness of lockdowns in suppressing the virus has been an assumption from the outset, but it is one that needs to be seriously examined. As Dr John Lee writes in the Spectator:

‘The Imperial College paper published on March 30 states that “Our methods assume that changes in the reproductive number – a measure of transmission – are an immediate response to these interventions being implemented rather than broader gradual changes in behaviour.” (my emphasis).

That is to say: In this study, if the virus transmission slows, it is ‘assumed’ that this is due to the lockdown and not (for example) that it would have slowed down anyway. But surely this is a key point, one that is absolutely vital to understanding our whole situation?

I may be missing something, but if you are presenting a paper trying to ascertain if the lockdown works, isn’t it a bit of a push to start with an assumption that lockdown works?

German-American epidemiology professor Knut Wittkowski is certainly one who casts doubt on the effectiveness of curfews, arguing the Covid-19 epidemic appears to be declining or even ‘already over’ in many countries. The lockdowns had come too late and have been counterproductive, he says.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ARTf4bpiXuI

He is not alone. One of the government’s most senior scientific advisors says some rules could be relaxed now that would bolster well-being without risking an even higher infection rate and death toll.

The true long-term threat of the coronavirus crisis seems to be dawning on governments elsewhere in Europe. Britain must also act before our economy and our society are fatally damaged.