Few remember Athelstan, Alfred’s grandson, who is neither lionized by the poets nor canonized by the Church. Yet he was a warrior king who is perhaps equal in greatness to Alfred and possibly rivals Edmund and Edward in piety.

See you the windy levels spread

About the gates of Rye?

O that was where the Northmen fled,

When Alfred’s ships came by.

-Rudyard Kipling, from “Puck’s Song”

“The high tide!” King Alfred cried.

“The high tide and the turn!“

-G.K. Chesterton, from The Ballad of the White Horse

The praises of Alfred the Great have been sung by hosts of poets and historians even apart from Rudyard Kipling and G.K. Chesterton, the latter of whom wrote an entire book-length epic poem in veneration of the great warrior king of the Anglo-Saxons. As to Anglo-Saxon kings, others might come to mind in addition to Alfred, especially the two who became saints, Edmund the Martyr and Edward the Confessor, both of whom were hallowed as patron saints of England until its patronage passed to St. George at the time of the crusades.

The praises of Alfred the Great have been sung by hosts of poets and historians even apart from Rudyard Kipling and G.K. Chesterton, the latter of whom wrote an entire book-length epic poem in veneration of the great warrior king of the Anglo-Saxons. As to Anglo-Saxon kings, others might come to mind in addition to Alfred, especially the two who became saints, Edmund the Martyr and Edward the Confessor, both of whom were hallowed as patron saints of England until its patronage passed to St. George at the time of the crusades.

Few, however, will remember Athelstan, Alfred’s grandson, who is neither lionized by the poets nor canonized by the Church. As we shall see, he is a warrior king who is perhaps equal in greatness to Alfred and possibly rivals Edmund and Edward in piety.

Athelstan was born in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex around A.D. 894. Five years later upon the death of his grandfather, his father, known to history as Edward the Elder, became king. Edward would rule for 25 years, laying solid political foundations for the kingdom his son would inherit in 924.

Edward is himself largely unsung in terms of historical recognition and has been described by contemporary British historian Nick Higham as “perhaps the most neglected of English kings.” The medieval chronicler William of Malmesbury judged that Edward the Elder was “much inferior to his father in the cultivation of letters” but “incomparably more glorious in the power of his rule.”

If we take William of Malmesbury’s judgment seriously, we might be tempted to proclaim Edward the Elder as an unsung hero of Christendom, but such a temptation would be a little premature. Unsung hero of England he might be, but he showed no great inclination to promote Christian civilization nor to support the presence of the Church. As William of Malmesbury confessed, he was “much inferior” to Alfred in terms of learning and culture, and contemporary British historian Alan Thacker wrote that Edward “gave little to the church indeed…Judging by the dearth of charters for much of his reign he seems to have given away little at all…More than any other, Edward’s kingship seems to epitomise the new hard-nosed monarchy of Wessex, determined to exploit all its resources, lay and ecclesiastical, for its own benefit.” Clearly this “hard-nosed” king was no hero of Christendom.

Unlike his father, Athelstan was particularly pious, defending the Faith as vigorously as he defended his kingdom. In terms of politics, he would become more powerful than either his father or grandfather, building on the solid foundations they’d laid. Whereas Alfred was the first King of the Anglo-Saxons, having united the various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the south of the country, Athelstan would become the first King of the English, following his 927 conquest of York, the last remaining Viking kingdom in England.

It is, therefore, to Athelstan’s reign that we can date the birth of the political entity which we now know as England, prior to which the country had been divided between various Anglo-Saxon regional kingdoms that were Christian and the parts of the country under Viking (pagan) domination.

However, even attributing the foundation of the English nation to Athelstan would not, in itself, make him a hero of Christendom. His heroic status in this respect rests on his piety and his practical efforts to promote Christianity during his reign. One of the most pious of all the Anglo-Saxon kings, he collected relics, founded churches, promoted learning, and laid the foundation for the Benedictine monastic reform that came later in the century.

One of his “Mass priests” appointed to celebrate Mass for the royal household was Beornstan, later to become Bishop of Winchester, who was probably the custodian of the considerable collection of relics that Athelstan had acquired. Known for his humility and holiness, Beornstan died on All Saints day in 934 and was widely believed to be a saint. Another member of Athelstan’s inner sanctum was St. Ethelwold who, according to his biographer, “spent a long period in the royal palace in the king’s inseparable companionship and learned much from the king’s wise men that was useful and profitable to him.”

Yet another future saint in Athelstan’s court was St. Dunstan, a Benedictine monk and future Archbishop of Canterbury, who would become one of the most popular saints in England for many centuries and with whom many pious legends were associated, especially those concerning his skill in defeating the wiles and deceits of the devil. (As an aside, Hilaire Belloc’s telling of one of these stories in his book The Four Men is simply delightful.)

King Athelstan died in 939. He had reigned for only fifteen years, but his short reign had changed the political, religious and historical landscape of England, justifying historian David Dumville’s claim that he was “the father of mediaeval and modern England.”

Whereas his grandfather Alfred and his father Edward had been buried at Winchester, Athelstan chose to be buried at Malmesbury Abbey in Wiltshire. This was where he’d buried his kinsfolk who fought and died at Brunanburh—the decisive battle in the north in which Athelstan led his army to victory over an invading pagan enemy—suggesting that he wanted to honour the memory of these men by being buried in their ranks.

However, William of Malmesbury believed otherwise. Describing Athelstan as fair-haired, “as I have seen for myself in his remains, beautifully intertwined with gold threads,” the chronicler wrote that Athelstan’s choice of burial place reflected his devotion to the abbey and to the memory of its seventh-century abbot St. Aldhelm. According to legend, Athelstan had donated many relics to Malmesbury Abbey, which supports William of Malmesbury’s reasoning that his choice of burial place was due to a desire to surround himself in the presence of the saints in death as he had surrounded himself with future saints in life.

Athelstan himself has not been canonized, and we do not know for certain if he is in the eternal company of the saints in the Kingdom to which his own kingdom held allegiance. We can know for certain, however, that he played a significant and crucial role in securing England’s place in the Christian family of nations and is, therefore, a hero of Christendom.

Republished with gracious permission from Crisis Magazine (April 2025).

This essay is part of a series, Unsung Heroes of Christendom.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

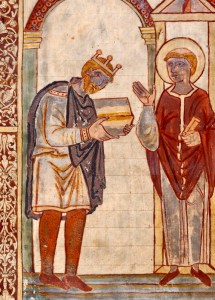

The featured image is “Frontispiece of Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert, showing King Æthelstan (924–39) presenting a copy of the book to the saint himself,” and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.