Sentimentalism is collectivized, but not like other ideologies. It has no party or movement or protests or marches or manifestoes as such. Rather it is a Spirit of our Age, the oxygen we breathe, our environment.

This title, only slightly ironic in both its parts, refers neither to any of the moon-June-swoon ditties that were crooned nine decades ago, nor to the doo-wop iterations twenty-five years later. In those the feeling was legitimately proportioned and properly placed. Rather it refers to the engorged and displaced feeling doing hard (if discrete) labor in the following examples, trivial, perhaps, but indicative.

This title, only slightly ironic in both its parts, refers neither to any of the moon-June-swoon ditties that were crooned nine decades ago, nor to the doo-wop iterations twenty-five years later. In those the feeling was legitimately proportioned and properly placed. Rather it refers to the engorged and displaced feeling doing hard (if discrete) labor in the following examples, trivial, perhaps, but indicative.

But before those, an assurance: yes, I already do hear it. What generation could not, indeed has not, wailed the same? After all, the most famous Jeremiad was shouted two-and-a-half millennia ago, and surely it was only the first one recorded. So: just another crank? To which my answer is a question: were they all wrong? And, if this time this Jeremiah is right, is there anything different about the affliction, or is it the same old same old, maybe like an old joke that you’ve never heard, or have forgotten? Or is it… different?

Here, then, those examples, which, I claim, do signal a difference, and a big one. Over the course of my fifty years of college professing (1967-2017), I’ve aborted the responses of thousands of students who, when answering a question, began with “I feel.” They were shocked to hear that I did not care about their feelings, as though I were therefore not caring about them. Instead wanted their thinking. “Why?” some would ask. “Because,” I would answer, “I know feelings are part of your identity, but this class is not about you.” To them that was news. Or this (less trivial). Some time ago we were told that our students ranked high internationally in academic self-image; they “felt good about themselves” in math. Unfortunately, they ranked near the bottom in math achievement. But wait, there’s more, and it matters. The response of some educators to that finding was approval. Self-esteem mattered more than an ability to do long division.

Since then Sentimentalism (as good a name as any, I think: better than ‘feelingism’ and still designating Feelings uber alles), fueled by Selfism (each of us imperial and, though not an island, may rule as though we were) has brought us deep into a personal and public self-indulgence that has become, not discrete but wanton. Moreover, this regime is so embedded in us psychically and culturally as to pass unnoticed, as a fish does not know its own wetness, thus mangling our personal behavior, social interactions, and public policies. To switch metaphors, it is our suffocating psycho-social kudzu.

On a modest—that is, a restrained—scale, the impulse, though unhealthy, is not necessarily noteworthy, but its roots are: it did not come upon us ex nihilo. Longinus, a Roman writing in Greek in the first century A.D., is the presumed author of On the Sublime, an incalculably influential work for nearly two thousand years. Mostly about style, especially figures of speech, his subject is the end to which those figures are deployed, and the title tells us all. “The effect… upon the audience is not persuasion but transport.” That is, the purpose of sublimity is “to scatter everything before it like a thunderbolt.” He continues, “our soul is uplifted… it takes proud flight, and is filled with joy.” But he concludes with a caveat: the sublime “is exposed to danger… when it is suffered to be unstable and unballasted.” Telling here is “the audience,” which is taken to be a reader, or people in a theater, not a circle of performative-hungry onlookers, let alone the public-at-large,

Seventeen centuries after Longinus, Edmund Burke gave us his own Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful:

The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature is astonishment…. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot… by consequence reason on that object which employs it…. [That passion] hurries us on by an irresistible force.

“Cannot reason on the subject.” Both writers see the intensity of the passion; what Burke describes Longinus warns against. But note: Burke has taken it out of a formal, or a private, venue. The sensation may be private, but its experience is likely public. From Burke’s day into the late nineteenth century the sublime had a nearly religious resonance. Still, so far, not too bad. After all, who has not enjoyed the bath of sublimity?

But, ironically, at just about the same time as Burke is writing, Jean Jacques Rousseau calls and raises on the advantages of strong passion:

Acts of consciousness are not judgments but feelings. Although all our ideas come from outside, the feelings that appraise them are within us, and it is through these feelings alone that we have knowledge of fitness or unfitness of the relationship between ourselves and the things that we must seek out or avoid.

Now we are defined—our “acts of consciousness”—by our feelings, and not merely our response to the sublime. Over-estimating the influence of Rousseau (and his followers) is almost impossible.[1]

In the English tradition, with aspects both healthy (in fact innocent) and malignant, the names to be reckoned with are eminently familiar to us. Wordsworth, Keats and Shelly, along with Byron and some other prose writers, inaugurate and sustain the Romantic Movement, our monumental shift in taste and the promotion of feelings to the apogee of artistic production and appreciation. (Coleridge, also a movement founder, was more restrained than his compatriots: as a Christian he already had a religion, one of the loci of strong sentiment, in this case devotion, adoration, and love.)

They told us we must both feel and examine those feelings as well, a self-consciousness that, though not brand new, was newly broadcast as healthy. For example, Wordsworth famously tells us that poetry is “emotion recollected in tranquility,” and Keats believes that “what shocks the virtuous philosopher delights the chameleon poet” who should “surprise by fine excess.” Byron, though, is at the extreme.

His belief was not only in giving license to passion but in licentiousness, not least of our appetites, and just there is the Empire of Sensational Feeling. But the most cringe-worthy of the group is Shelley, who thought poets the “unacknowledged legislators of mankind”—not of poetry, nor of a private response to nature, nor even of a personal quest for satisfaction, but of mankind—and who, in his “Ode to the West Wind,” wrote “I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!” thus celebrating the fully Exhibited Self, specifically its suffering, victimized vulnerability. And we should feel along.

These writers are certifiably poets who pivotal in their influence, and often in the varied beauties of heir verse, sometimes—sometimes—including their depths of passion. Yet not long after their floruit Herbert Spencer, the apostle of social Darwinism who originated the phrase “the survival of the fittest”, called and raised. He tells us that “opinion is ultimately determined by the feelings, and not by intellect.” Sure, he does not say ‘truth’ is so determined, but neither does he make the distinction between it and opinion. A lesson here is evident: all movements have their excesses, but once they overwhelm the culture-at-large they no longer seem excessive; they become norms. The tail wags the dog.

In the twentieth century, psychoanalysis (“and how do you feel about that?”: low-hanging fruit to be sure) has led to letting it “all hang out,” as the going phrase once was. And so we did, when millions of baby-boomers became the scourge of all parents in the 1960s, that is, when the country became adolescent.[2] Pathetically, many of those parents joined in, with their sandals, pony tails, and bra-burning exhibitions. Whitman had sung of himself, and the Beats taught the generation to Howl.

Soon popular music would become apocalyptic (think Metal, Heavy or not), theater “broke boundaries” (remember Hair?) They gave us not only the Black Panthers (and Leonard Bernstein’s party for them: I feel you, man), but the riots that accompanied the Democratic national convention in 1968, with a riot or two that burned some cities mixed in. And it gave rise, too, to Woodstock: the trifecta of the Summer of love, unbridled sex, drugs, and rock and roll. But not to worry. Prostitutes and porn stars are now ‘sex workers’, right there with, say, construction workers, and, lest we forget, “It’s Hard Out There for a Pimp” (Academy Award for Best Original Song, 2006).

A far spell from Longinus’ ‘sublime’, but certainly a fine approximation of Shelly’s, Byron’s and Spencer’s Weltanschauung, which is now ours. But also, I insist, a far cry from plain, old hedonistic excess. A man might womanize, or cross-dress, or have a boyfriend, or overeat, -drink, or -smoke, but none of it became our business, or a cause, or was profferred as a norm, perhaps to be celebrated, or taught in schools.

‘Sentiment’, ‘sentimental’, ‘sentimentality’. Though overlapping these concepts are distinct; respectively, an emotion, the indulgence of one or more emotions, and the habitual indulgence of them, preferably of the most intense. Each offers rewards: a sense of vitality (perhaps as excitement: I am alive), or relief (as catharsis), or sometimes as a tempting sense of danger (an invitation to deeper, unknown, involvement), or often as self-satisfaction (as in virtue signaling, our particular pleasure du jour). Feelings may come and go, and mostly go, as C.S. Lewis said, but he underestimated the cultural breadth and depth of our appetite for their cultivation.

Thus our plunge into a quasi-religious, or better yet, a virtual ideology, the belief in the over-arching reliability of feelings. Think of an automobile. To go anywhere it needs gasoline, but gasoline does not steer. That requires judgment, intellect. Sentimentalism is the belief that the mere existence of a feeling is not only fuel but the compass, too. In that way Sentimentalism is precisely the engorgement and displacement of feelings.

This inordinacy, irrupting from the red meat of any adolescent, the Feeling Self, is at the center of a constellation of concepts: appetite (of course), identity (now fungible), aggrievement (the Self is ever-sensitive), and pride (often counterfeited, as in the winning of a ‘participation trophy’). Any number of words, hovering over and around this garden of earthly delights like wasps, are symptomatic of the affliction, from ‘selfish’ and ‘egotistical’, to ‘narcissism’ and ‘sociopathy’, as well as ‘self-fulfillment’, ‘right to happiness’, and a host of socio-cultural embellishments (not least in advertisements: “because you deserve it,” women are told; “be all that you can be,” men are told) that inflate the Self.

Furthermore, because feelings (the stronger the better) promise undiluted possessiveness they are hard to resist. I may own nothing else, but my feelings are mine. So the more of them I have, and the more intensely I have them, the more of a Self am I, rather like very rich people who need even more, as validation, or Tolkien’s Gollum grasping after his ‘precious’.

Now, though, I think a caveat is in order. Some readers may have fallen prey to Early Onset Objection Syndrome, either in the brain or, more likely, in the ‘gut’ (a seat of impulses which for a very long time we have been urged to “go with”). To those readers I ask that they remember my shorthand definition of Sentimentalism: engorgement and displacement. I do not suggest that we all become some version of Mr. Spock, the affectless Vulcan from Star Trek. We need to distinguish legitimate feelings, even necessary feelings, from the cultish (often artificially catalyzed) ideology of Sentimentalism—though making distinctions is itself nearly impossible in a febrile atmosphere of feelings run amuck.

For example, there is a place for righteous anger. What George Floyd suffered, which became (I am convinced) first-degree murder, aroused an anger nothing less than righteous, as do so many social enormities. But the riotous (literally) response was engorged, displaced and, especially, self-indulgent. As someone who has struck someone else, and to great effect, I do know how good that feels. I also know how wrong it was (at least in one instance). Alas, as with those educators who thought self-esteem matters more than actual achievement, too many pundits not only failed to chastise the hooligans who burned cities but also approved of their mayhem.

Exactly there arises a perfect example of a spectral affliction. For a long time now we’ve come to see almost everything that happens, or is spoken, or is even thought, through the Left-Right prism, as though placement on that spectrum were the purpose of all socio-cultural argument. It must not be.

Here is an instance of what used to be a commonly-shared revulsion (shared, in fact, by Jesse Jackson, Daniel Moynihan, Jimmy Carter, Dorothy Day and—gulp!—Margaret Sanger). There is abroad a great Sentiment to protect the invisible, the voiceless, the helpless—perfectly legitimate—unless they are unborn children. Yet at any mention of their protection argument ceases and a genuflection to the abstraction of Choice is required. That genuflection brings the good feeling devolving upon a sympathetic, and thus enhanced, Self. Sentimentalism aborts thought.

Never mind: my argument is not about this or that example, or any cluster of examples, but about the toxicity that is Sentimentalism, the hub of a wheel at which many spokes—high culture and low, ordinary speech, politics and public policy, even the Natural Law, and of course the Self and the self’s Identity—meet. Think of those ads that promote deep pity (mostly for animals), or self-indulgence, or the pop music that too often celebrates license, or various public figures. Bill Clinton comes to mind, he whom Jesse Jackson once described as all appetite but who has suffered no serious public opprobrium. Byron would have loved them. Passions rule, especially when the sentimentalists are conditioned and sometimes even paid by cynics even more ideologically driven than they. Think Antifa and Black Lives Matter and Proud Boys and Christian nationalists, Timothy McVeigh and….

One element, I think, that compels our immersion into this wetness, the fertilizer, so to speak, of sentimentalism is sincerity. It makes the Self real, and real selves simply must be respected, no matter the object of that sincerity. Each of us—we do not need to be woke—could think of countless circumstances that not only invite but require a sincere emotional response; but I believe that many fewer of us could identify instances of engorgement and displacement of emotion, or would even care to do so, because we pretend to a sincerity equal to the sentimentalist practitioners, those who ‘act up’. After all, they are sincere in their allegiance to a cause.

So, the rage, despair, lust, or sympathy are real, in the moment, and must be respected, for to do otherwise is to disrespect a Self. “But that’s how I feel,” we say, so sincerely, as though it is therefore case closed; or “I feel so strongly about this”; or “I have very deep feelings.” Under those circumstances the possibility of undue (vastly disproportionate) engorgement, displacement, or sheer irrelevancy rarely occurs to the True Believer, and, if it does, such disproportion often becomes the point. Only the extreme feeling can be sincere and therefore real, as though there were a sincerity meter and sincerity was a competitive event.

Finally Sentimentalism is collectivized, but not like other ideologies. It has no party or movement or protests or marches or manifestoes as such. Rather it is a Spirit of our Age, the oxygen we breathe, our environment, the kudzu of sexual exhibitionism, or unbridled political rhetoric, or rampant pornography, the violence of some song lyrics, or the anti-musicality of some popular genres. Constantly over-excited and hyped up, we no longer recollect in tranquility. And for too many, that feels too good.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Notes:

[1] See Steven Kessler’s work in The Imaginative Conservative, especially “When Feelings Become Facts,” July 17, 2018.

[2] In The Culture of Narcissism (1979) Christopher Lasch told us all about the Me Decade, one of actual or virtual teenagers.

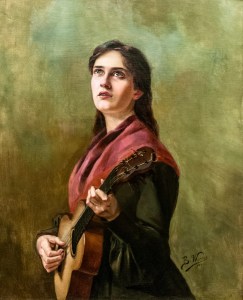

The featured image is “Sentimental Song“ (1904), by Bertha Worms, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.