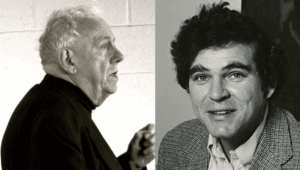

This spring, two emeritus philosophers at the University of Notre Dame—Alasdair MacIntyre and David Solomon—died. No doubt the advocates of progressive “diversity” would say that these two were symptomatic of the lack of that magical quality. But what made for their diversity was a different set of gifts that enriched the University of Notre Dame, academia, the Catholic Church (and Christians generally), and indeed the world of ideas.

I am certainly glad that the Trump Administration is doing its best to crush the ideology of DEI—Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. While the terms themselves can be used in ways that are positive and laudable, the way in which they are used in the theology of this false trinity is such that they tend to mean the opposite of what they sound like to ordinary ears. Inclusion is all about excluding the right people. Equity is about favoring the right people. Diversity is sometimes about getting people who differ together, but this is, quite literally, only a skin-deep concern. DEI advocates like people of different hues, but only if they all hum the same leftist tunes.

I am certainly glad that the Trump Administration is doing its best to crush the ideology of DEI—Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. While the terms themselves can be used in ways that are positive and laudable, the way in which they are used in the theology of this false trinity is such that they tend to mean the opposite of what they sound like to ordinary ears. Inclusion is all about excluding the right people. Equity is about favoring the right people. Diversity is sometimes about getting people who differ together, but this is, quite literally, only a skin-deep concern. DEI advocates like people of different hues, but only if they all hum the same leftist tunes.

We can put the “E” and the “I” aside for now. But two sad events this spring have gotten me thinking again about the proper notion of diversity within the context of higher education. Properly understood, diversity is a good thing and necessary for universities.

This spring, two emeritus philosophers at the University of Notre Dame died. No doubt the advocates of progressive “diversity” would say that these two were symptomatic of the lack of that magical quality, two white men who both spent most of their lives looking at the world through the lens of the western and, eventually, Catholic intellectual tradition. Even Thomistically inclined. Where is the diversity in that?

The more famous of the two was the Scottish-born Alasdair MacIntyre, whose contributions to moral and political philosophy, philosophical theology, philosophy of education, and many other fields were legendary. The Amazon page for his name gives an immediate twenty-one titles either written by him or about him. A longer search would dredge up many more. He passed into eternity at the ripe old age of 97. Old-fashioned leftists would be more likely to give him something of a pass on the diversity question because of his earlier Marxist mindset and his continued hatred for capitalism and skepticism about the nation-state—even if he eventually entered the infamous Catholic Church.

Professor MacIntyre’s (he never earned a Ph.D.) was a longer life than that of his younger colleague, the moral philosopher David Solomon, who died at the still respectably long-lived age of 81. He got his biblical three score and ten allotted for the strong—plus one. Dr. Solomon was not as prolific or as high profile as Professor MacIntyre. Though he wrote many articles on virtue ethics, bioethics, and medical ethics, a quick Amazon search for books doesn’t yield any readily available for Dr. Solomon.

And therein lies the tale of true diversity in higher education. The kind of diversity needed in a university—indeed, in most institutions—has little to do with the percentages of men, women, whites, blacks, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders, or whatever other identity one has chosen to make central to a curriculum vitae or a job search. It largely has to do with what kind of gifts one brings to the job.

Modern higher education has valued the high-profile scholar whose genius and creative thought makes a big splash in the academic world—and, if possible, in the broader world as a “public intellectual.” Professor MacIntyre was certainly “that guy.” His After Virtue (1981) was regarded by many as the most important book on moral philosophy in English in the twentieth century. He won a great many awards, was elected to all those prestigious groups with “Academy” in their name. Although he taught at a great many institutions, it looks as though he was even more of a wanderer due to his being invited to serve as a researcher or visiting distinguished professor in even more places.

No wonder. Unlike many academic philosophers, particularly those in the Anglo-American “analytic” school, he was not obsessed with demonstrations in symbolic logic. He wrote clear and even memorable prose. The conclusion to After Virtue is endlessly cited:

And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

Not a theatrical speaker, his style at the podium delivering such lines was nevertheless memorable. And his reaction to questions could be just as witty and sometimes shocking. He liked to observe that his Greek teacher beat students who didn’t learn their verbs. After a pause, he would then reveal that he did learn those verbs. He could be dismissive of those whose thoughtlessness was uttered through the microphones. I didn’t really know him, but he once chaired a session my wife and I were presenting at a conference. In the question period, someone asked us a particularly stupid question aimed at debunking us. He batted it down, eliminating for us the need to choose between doing so ourselves or trying to talk around the insipidity of the comments and be positive. (We were elated: “MacIntyre defended us!”) Students of his at Duke and Notre Dame loved to talk about the fact that he gave the straight dope in class, too, demanding excellence from and raising up the level of undergraduates who may have wondered why they had to be in philosophy in the first place.

Such geniuses are part and parcel of any institution, especially universities. Yet they are not the only kind of people you want. Dr. Solomon was a brilliant thinker, but he was also one who sacrificed some of the time he could have used for researching and writing to do other things just as important for intellectual communities. Dr. Solomon was widely known for his work on Notre Dame’s campus, both teaching and founding programs that made a serious difference on that campus. One tribute says he directed 36 doctoral dissertations, a record for the Notre Dame philosophy department. (The late Ralph McInerny directed 50, but many of them were in Notre Dame’s Medieval Studies department.) That kind of labor-intensive work with students is not remunerated either monetarily or in prestige. He didn’t neglect undergraduates either, serving over his nearly five decades as director of: undergraduate studies in philosophy, the Notre Dame London program, and the Arts & Letters/Science Honors Program. Of the last, he was also the founder.

His most important foundation, however, was what came to be known as the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture at Notre Dame in 1999. The dCEC (as it is currently abbreviated) started doing extracurricular formation work on campus and also started bringing in scholars to Notre Dame to work on projects connected to the Catholic intellectual tradition both through fellowships and through many conferences it hosted. The most famous of these is the ongoing fall conference that now attracts upward of 1200 people to Notre Dame’s campus every October or November (never on a football weekend!).

Unlike most academic conferences, this one always aimed for something more than getting a line on the CVs of professors and graduate students who need to “present at an academic conference” and network for jobs. The fall conference was always something more like a carnival for those who wanted to think about the issues of the day through a Christian lens. Dr. Solomon, a Baylor alumnus, always had busloads of Baylor students and faculty showing up for the conference—as well as Protestant and Orthodox Christian scholars from all over the place who were comfortable hanging out with papists whom they understood to be friendly interlocutors on the most important ethical, cultural, and spiritual issues of the day.

There are always non-academics, too. Undergraduates, high school students, homeschool moms, doctors, lawyers, and all manner of people looking for truth in all the right places have always come. Dr. Solomon, who presided over the opening of the conference and the big banquet meal, always played the impresario for the whole event. He got to know many of the people—including the young children who ended up at the conference with their parents. And he knew how to set the tone for the events: he knew that fun is not the opposite of serious. He knew that big and tough issues needed to be expressed for large groups in language that could be understood. And he knew that welcome is an important aspect of creating a community, even temporarily, that takes joy in the truth. That made him an excellent leader of seminars for groups of academics from different disciplines as well.

From the vantage point of wokeness, these two scholars are now mere Dead White Males, Philosophers of Pallor, indistinguishable from all others. But anybody who looks beyond our rather dim identity politics knows that what they shared most was not a need for sunscreen but a way of thinking that took truth seriously. What made for their diversity was a different set of gifts that enriched the University of Notre Dame, academia, the Catholic Church (and Christians generally), and indeed the world of ideas.

A former colleague liked to make the analogy to baseball. When hiring, you don’t simply draft pitchers for your team; you need catchers, outfielders, third basemen, and all the rest. But academics tend to do something similar to teams drafting only one position. “Get me the best philosopher!” they like to say, referring only to the genius-publishing model represented by Professor MacIntyre. But intellectual communities also need people with other kinds of gifts. Administrators, mentors, and impresarios such as David Solomon are often just as important to the life of these institutions.

Of course, the types I have discussed above do not exhaust the categories of real diversity in academic or other institutions. But in looking at these two great but unmistakably different men, we can see that diversity can be our strength—as long as we’re looking for the right kind.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image combines an image of W. David Solomon, courtesy of the University of Notre Dame Archives, and an image of Alasdair MacIntyre, uploaded by Sean O’Connor, and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.