THE UK National Debt is the total amount various governments have had to borrow to make ends meet, or to invest, they all say, for the future. Fifty years ago in 1974 it was £52billion, otherwise £52,000,000,000. Quite a lot and of course a hefty chunk of interest is due on that kind of sum. You might think subsequent governments would strive mightily to bring it down.

What has actually happened since 1974 is a very interesting story. Consider first what each Prime Minister said on taking office or soon after, then see how her or she dealt with this monstrous debt.

Harold Wilson, Labour, PM for the second time 1974-1976

Following an earlier and very similar quotation from Aneurin Bevan, he described the essential problem of a democracy: ‘How to persuade the people to forgo immediate satisfactions in order to build up the economic resources of the country.’ ‘Immediate satisfactions’ come with borrowed money. Strict financial control is a vote loser. How have succeeding governments dealt with this problem?

James Callaghan, Labour, 1976-79

‘This time we are not borrowing . . . to pay for yet another short-lived consumer boom . . . We are borrowing . . . to pay for our huge investment in the North Sea.’

That and the sterling crisis meant he had to go to the IMF for a loan.

Margaret Thatcher, Conservative, 1979-1990

‘The industrial countries that out-produce and outsell us are precisely those countries with better social services and better pensions than we have . . . It is because they have strong wealth-creating industries that they have better benefits . . . Our people seem to have lost belief in the balance between production and welfare.’

How sensible, and over the years 1988-90 she reduced the debt by about £16billion.

John Major, Conservative, 1990-1997

‘I certainly hope . . . to build a society of opportunity . . . I believe very firmly in the 1990s that we will have a decade of the most remarkable opportunities.’

Later comments said he deserved more credit than he was given at the time. He borrowed relatively small and decreasing amounts over the years 1995-97.

Tony Blair, Labour, 1997-2007

‘I know well what this country has voted for today . . . a mandate for New Labour . . . to get those things done in our country that desperately need doing for the future . . . a Government that remembers that it was a previous Labour Government that formed and fashioned the welfare state and the National Health Service. It was our proudest creation. It shall be our job and our duty now to modernise it for a modern world, and that we will also do.’

Ultimately borrowed like the others but reduced the debt by £41billion over the two years 2000-01.

Gordon Brown, Labour, 2007-2010

‘This is our vision: Britain leading the global economy . . . a world leader in energy and the environment from nuclear to renewables . . . modern manufacturing too.’

He was hit by the 2008 financial crisis so had to borrow a lot.

David Cameron, Conservative, 2010-2016

‘One of the tasks that we clearly have is to rebuild trust in our political system . . . making sure people are in control . . . the politicians are always their servant and never their masters . . . I want to make sure that my government always looks after the elderly, the frail, the poorest in our country.’

Whatever he did it cost a lot of money the country didn’t have.

Theresa May, Conservative, 2016-2019

‘When we pass new laws, we’ll listen not to the mighty but to you. When it comes to taxes, we’ll prioritise not the wealthy, but you. When it comes to opportunity, we won’t entrench the advantages of the fortunate few.’

Like the rest, more borrowing needed to avoid anything unpopular.

Boris Johnson, Conservative, 2019-2022

‘My job is to make your streets safer . . .to make sure you don’t have to wait three weeks to see your GP . . . we will fix the crisis in social care once and for all.’

He was hit by covid and the subsequent policy decisions meant much borrowing.

Liz Truss, Conservative, 2022

‘We need more investment and great jobs in every town and city across our country . . . I will get Britain working again . . . I will make sure that people can get doctors’ appointments and the NHS services they need.’

Seven weeks is just not enough time to do anything.

Rishi Sunak, Conservative, 2022-2024

‘A stronger NHS . . . better schools . . . safer streets . . . control of our borders . . . levelling up and building an economy that embraces the opportunities of Brexit, where businesses invest, innovate, and create jobs.’

None of that is cheap and he was still dealing with the aftermath of covid.

Keir Starmer, Labour, 2024-

‘We will rebuild Britain . . . our NHS back on its feet . . . secure borders . . . cutting your energy bills for good . . . world-class schools and colleges . . . affordable homes.’

In his first year he has already borrowed an extra £151billion.

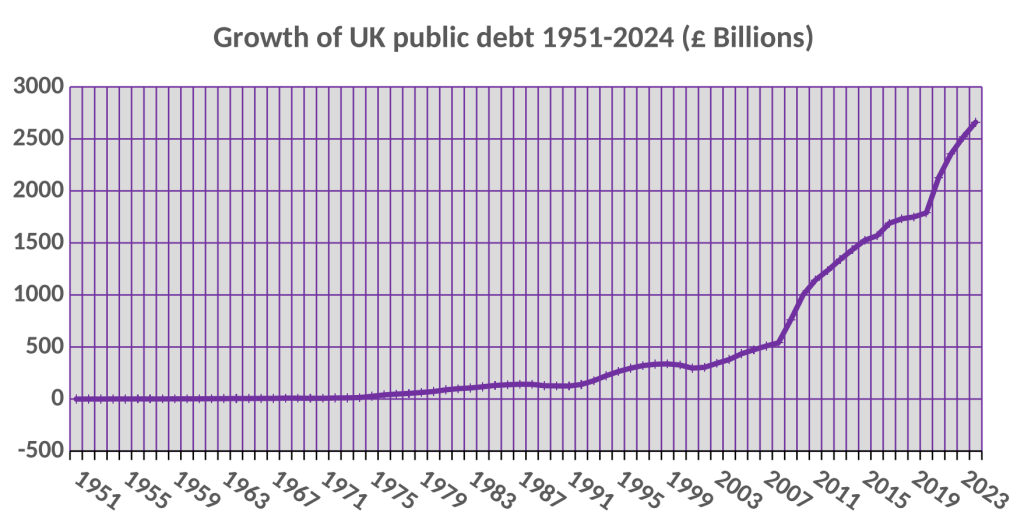

The National Debt now stands at around £2.8trillion according to government data. This is £2,800,000,000,000. Fifty-four times larger than in 1974. What happened?

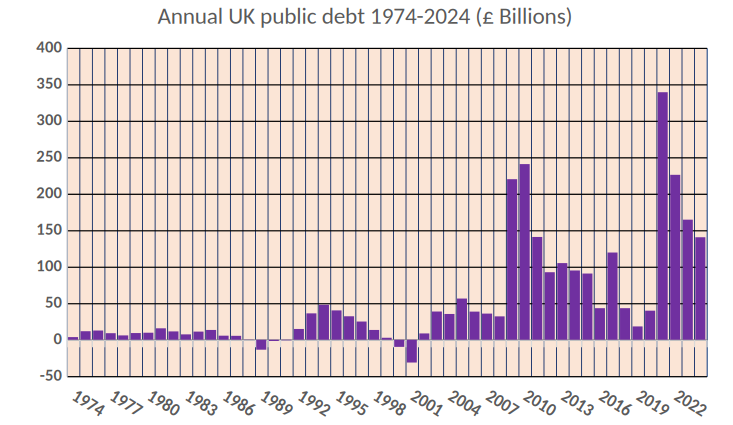

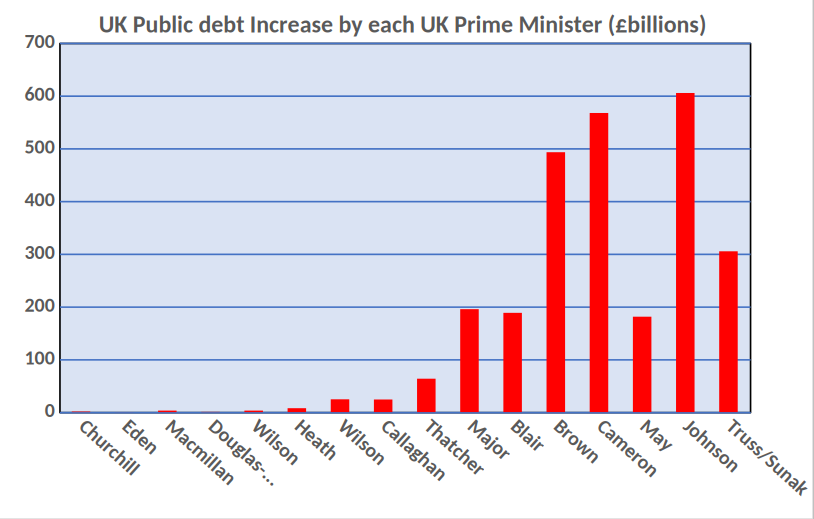

Three pictures tell the story. But one important comment first: many other countries have the same problem. The US debt, for instance, is $36.2trillion (£27trillion).

Picture 1: Annual debt increase

Picture 2: How the debt amount varied each year.

This shows clearly the effect of the Financial Crisis 2008 and Covid in 2021. Note the red columns marking Margaret Thatcher’s attempt to reduce the debt 1988-90, then Tony Blair’s attack in 2000-01.

Picture 3: How any reductions didn’t last as each government tried to keep their electorate (more or less) happy.

There we have it, the reasons for that £2,800,000,000,000 debt which in 2023/24 cost the country an interest payment of £107,000,000,000.

Think what we could have done with that £107billion. New hospitals, 20 small modular nuclear reactors at £2billion each, more nurses, GPs, buses, roads, railways, clinics, houses. Potholes filled promptly and properly.

Aneurin ‘Nye’ Bevan was a minister in the Attlee government 1945-51 and is known as the architect of the National Health Service. ‘There is,’ he said, ‘one important problem facing representative parliamentary government . . . It is being asked to solve a problem [in] which so far it has failed . . . how to reconcile parliamentary popularity with sound economic planning.’

Parliamentary popularity versus sound economics? You’ve seen how that question was answered.