In reflecting on the lives of Fr. Gereon Goldmann and Dr. Takashi Nagai, and the era of war in which they lived, I was struck by how the Catholic faith—when truly lived with dedication—surpasses any national or ethnic enmity. It unites any and all in a universal goodness, mercy, wisdom, and love.

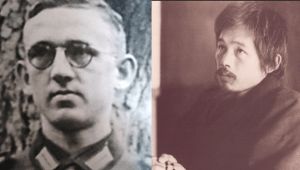

While Germany and Japan under the control of militarist leaders were making war against the Allies in World War II, a heroic witness to the distinctive strength of the Catholic faith was lived in the midst of destruction and conflict by two men in particular, one in Japan and the other in Germany. These were not the only ones, but the stories of these two men have become well known and are worth reviewing. These two highly intelligent men—one a medical doctor, scientific researcher and professor, the other a Franciscan seminarian—both showed unique strength of character in living the teachings of Christ in the midst of exceptional darkness and danger, refusing to bow down to policies with which they didn’t agree or to avoid the enormous challenges they faced.

While Germany and Japan under the control of militarist leaders were making war against the Allies in World War II, a heroic witness to the distinctive strength of the Catholic faith was lived in the midst of destruction and conflict by two men in particular, one in Japan and the other in Germany. These were not the only ones, but the stories of these two men have become well known and are worth reviewing. These two highly intelligent men—one a medical doctor, scientific researcher and professor, the other a Franciscan seminarian—both showed unique strength of character in living the teachings of Christ in the midst of exceptional darkness and danger, refusing to bow down to policies with which they didn’t agree or to avoid the enormous challenges they faced.

The first in my account, Dr. Takashi Nagai, was a practicing physician in Nagasaki, Japan and a professor of medical science. In 1934, he was assistant to the chief of the Radiology Department of the Nagasaki Medical University, as a recent graduate of the medical school. In June of that year also he was baptized as a Catholic, after growing up in Shinto family. How did this conversion come about?

Takashi’s journey into the Church began when as a medical student he lodged with the Moriyama family who had descended from the “Hidden Christians,” Catholics who were outlawed by the Japanese authorities for 250 years but quietly passed on their Catholic faith and devotions within their families for seven generations. They lived as farmers and fishermen, settling to the north of Nagasaki in what became the Urakami suburb and Christian community. The Moriyamas had a daughter, Midori, who was a teacher, and she became attracted by Takashi. She prayed for him, particularly when he was called to serve in the Japanese army in China, and sent him a catechism to read. Takashi noted that the catechism asked a lot of the same questions that highly-respected Japanese religious men had asked in an earlier epoch, and that the catechism had clear answers. He also read Blaise Pascal whom he respected as a scientist and noted that Pascal said that you could only discover the living God if “you went down on your knees.” He remembered that the Moriyamas and their daughter Midori went down on their knees in prayer frequently. He had been invited to attend a Christmas midnight Mass at the Urakami Cathedral and had felt a sense of “Someone” present in that holy place. In contemplating the simplicity and humility of the Holy Family, he was struck by his own materialism, selfishness and superficiality.

Takashi continued to think deeply about these questions. He was struck by the horror and meaninglessness of war in his first experience as a soldier in China. He began to question science and progress. On his return, he went to visit the rector of the Cathedral, Fr. Moriyama whose father and uncle had been tortured for their faith in 1864. This wise and gentle priest was a great help in his counseling and Takashi started going to Sunday Mass regularly, studying the Bible. Soon he was ready for baptism. Although he had to face his Shinto father’s opposition, he went ahead, eager to leave his former darkness and live in the light.

Another wonderful story is the love that had developed between Midori and Takashi and their eventual marriage. The detail of all these stories and much more are contained in the biography, A Song for Nagasaki, by Fr. Paul Glynn, a Marist priest who was a missionary in Japan for 25 years. I want to share some of the important parts of Dr. Nagai’s life, but one should read this inspiring book for oneself.

From the time of his baptism, grace was apparent in Takashi’s life. He joined the Society of St. Vincent de Paul and went on field trips to give free medical service to the poor, getting other doctors and nurses to join him. During his second term of service in the war in China on the front as chief surgeon, he showed concern for all the wounded, including the Chinese. He set up a medical group to help the Chinese civilians, especially the children, and contacted the Society of St.Vincent de Paul in Nagasaki to send help, and also got the Chinese Vincentians to give aid. This helped to dissipate distrust. When war weary, he would turn to Pascal, to the psalms and the gospel, which brought him peace and helped him entrust all to God’s Providence. In a serious crisis, he prayed the rosary and was delivered.

Back at Nagasaki Medical University Hospital, he was appointed chief of the medical staff. When he was assistant to the professor researching radiation, he became fascinated with radiation, including the study of atoms and the development of x ray technology. He was so dedicated to the use of x ray to diagnose his patients that he took extra risk in spending long hours in this work, over-exposing himself to radiation. As a result, he developed leukemia: prognosis “2-3 years life expectancy, death lingering and painful.” His medical friends were appalled, but Nagai responded, “Doctors, we have to be realists, and one day every one of us must become a patient, a terminal patient.” When he apologized to the university president for his carelessness, the president replied, “No Nagai-kun, you were not careless. You are sick because you cared for those long lines of patients needing help, with no one to x ray them but you.” In private, however, Nagai trembled and turned to pray to Christ of Gethsemene for strength to carry this heavy cross. His wife Midori, whom he feared to tell, was courageous and holy in her response to the news; she took out the 250 year old family crucifix and knelt before it to pray.

In the meantime, the news of Hitler and Mussolini and the announcement of war in Britain and America was foreboding. The government of Japan was under the control of militarists with whom many in the country, including Nagai, didn’t agree. Then Japan’s prime minister signed the alliance with Germany and Italy. There were talks in Washington between Japan and the U.S. On December 8, Nagai and Midori went to 6am Mass to celebrate the feast of Mary’s Immaculate Conception. Nagai prayed fervently that there would be no war between Japan and America. He had no illusions about the strength of America. But on his way to the university, a loudspeaker announced the news of Pearl Harbor. Nagai was chilled with a terrible presentiment. In addressing his students, he warned them of what was to come, knowing from his experience of war in China, that they all would be involved, many of them injured, some of them killed. The students were shocked.

But they loved their country and cooperated with defensive measures. Nagai was asked to organize air-raid responses in his suburb. He appealed for help from the Women’s Neighborhood Association that Midori had worked with. He warned them, “We may be bombed any time now. You must learn how to care for the injured… You will need courage, but above all you will need love… love great enough to lay down your lives for your fellow citizens.” He built an underground operating theater with medical supplies. Soon American air raids would begin on the Japanese mainland. While Nagai did not believe Japan was in a just war, his main concern was for the safety of civilians and help for the wounded. So he poured his energy into conducting air raid drills as air raids became progressively more frequent.

Then came the fateful day, August 9, 1945. Nagai was in his office preparing a lecture for his class at 11am when the window pane rushed in and “a giant hand seemed to grab me and hurl me ten feet.” Glass whirled around him and a piece of it cut into the artery in his right temple, blood flowing over him. He had seen a flash of blinding light and thought a bomb must have fallen on the university entrance. Objects in his room and outside were doing a weird dance, some falling on him until he was buried under debris. He heard the sound of crackling flames and smelled the smoke. Panic struck his heart and he began to pray to the Lord for forgiveness of his sins.

The concrete descriptions of what happened when the atomic bomb fell on Nagasaki are riveting. One needs to read this book to experience the unforgettable horror of this tragedy. But it is also inspiring to find how even in the midst of the most terrible sufferings, human nobility can arise as witness to the depth of the human spirit.

Nagai, being conscious but completely trapped, could only call out “Help, Help.” A nurse heard him but could not get into his room. Thankfully she found five other staff that formed a human chain that was able to get him out. Although badly hurt, he immediately took charge of the situation, calmed the others and led them to look for other staff. Most were dead, only a few survived. Only one student had survived. (80% of the patients and staff perished.) Panic was rising in them. Fire was threatening. Yet Nagai led them to check the patient wards to save whom they could. Medicine, stretchers, instruments were all smashed. They felt helpless. Nagai, with his head bound but still bleeding, said to the rest: “All we have is our knowledge, our love, and our bare hands.” They took the surviving patients up the hill, away from the fire. But after carrying two patients, Nagai collapsed. When he recovered, he saw that the organization was disintegrating and panic was returning. People from the city were pouring up the hill to the hospital to get help, but the staff could barely help their patients and were losing their nerve. But Nagai called out to look for a Japanese flag, which the others thought of little importance. Nagai found some white cloth, took off his blood-soaked bandage and made a red circle on the white background—the Japanese flag! He mounted it on a bamboo pole and set it on the hill above them. A rallying point! Nagai had remembered from the war in China how a powerful symbol or bold action would reverse the shock and panic in a war. Now they had a headquarters. The surviving staff set up small units in the hills to treat the injured. They could only give minimal care and bring some water from a well to quench thirst. But the staff were developing a sense of being bound together in this incomprehensible fate. Even after dark they went out looking for any survivors, although they faced various dangers. Black rain was falling, fires belched carbon dioxide leaving little oxygen to breath. They continued to absorb radiation, beginning to feel radiation sickness. They see Urakami Cathedral go up in flames. Everywhere they looked it was a nuclear ash-scape, nothing alive, nothing green.

Refugees fled to the mountains. Nagai looks for his wife among them but she doesn’t come. The horrible realization swept him: She is dead. She had stayed in their house, to be available to him, although their two children and grandmother had gone to the mountains. When some doctors and nurses from the military hospital arrive to help, Nagai is free to think about his own family. His children and grandmother were safe, but Midori? He returns to what was their house, now a collapsed rubble, and finds Midori “a black lump of charred bones.” But in the bones a glint revealed a melted rosary that she had been praying when she died. He gently gathers her bones. He finds that all his textbooks, case histories, classic literature he loved, his x-ray studies all had gone up in flames. The only thing left was a metallic print in which one of his poems was legible. Overcome with this loss of all that he loved, he collapsed weeping and fell unconscious for several hours. When he awoke, he went to his children and grandmother in the mountains, a healing time. But the next day, he again gathered the remnant of the x-ray staff to join him in the mountains to treat the sick refugees who had fled there, setting up medical units in tents to treat as many as they could.

Before the bomb, the Allied Potsdam Proclamation had asked for the unconditional surrender of Japan, July 28, 1945. But Japan’s Prime Minister rejected this. The Japanese do not surrender. When the Emperor, who normally was never involved in government business, heard of the Nagasaki bomb, he called the Council of War and told them that Japan would accept the Potsdam surrender and that he would broadcast the decision to the public at 12 noon August 15. This date, the feast of the Virgin Mary’s Assumption into heaven, was particularly significant for Nagasaki Catholics because it was the date St. Francis Zavier had arrived to preach the gospel in Japan and the Cathedral of Urakami was dedicated to the Assumption. However when the Japanese people heard the decision, they burst into tears. Japan was dead! They were overcome with grief. They feared the Americans would invade, kill the men, rape the women and destroy their culture.

Nagai and his staff also fell into depression and the will to act. But the next day they recovered and continued their mercy missions. Nagai, however, was developing severe symptoms. Not only did he have leukemia but nuclear radiation had increased its effect and he had lost much blood from his injury. He fell into a coma. He was near death. The doctors and nurses monitored him carefully, feeling the end was near. But Nagai heard a voice in his head telling him to pray to Maximilan Kolbe. So he did. Suddenly the bleeding stopped and he began to recover. He felt clearly this was a miracle of intercession by Kolbe whom he knew only slightly from his time in Japan. He did not know that Kolbe had died in a Nazi concentration camp four years earlier.

By October, most of the radiation had cleared, and many survivors were beginning to return. Nagai encouraged them to help rebuild the suburb of Urakami, suggesting they build simple huts for themselves while helping to rebuild first the Cathedral, then the hospital and the schools. He built a simple one-room hut for himself with enough room for two sleeping mats. Others built huts around his. The children and grandmother moved in with him, although he eventually built a second hut for them.

The bishop planned an open-air Requiem Mass for people to pray for their dead. He asked Nagai to speak on behalf of the laity. Nagai thought deeply of what to say. Here is part of his speech:

“I have heard that the atom bomb… was destined for another city. Heavy clouds rendered that target impossible, and the American crew headed for the secondary target, Nagasaki. Then a mechanical problem arose, and the bomb was dropped further north than planned and burst right above the Cathedral…. It was not the American crew, I believe, who chose our suburb. God’s Providence chose Urakami and carried the bomb right above our homes. Is there not a profound relationship between the annihilation of Nagasaki and the end of the war? Was not Nagasaki the chosen victim, the lamb without blemish, slain as a holocaust on an altar of sacrifice, atoning for the sins of all the nations during World War II?”

The congregation was shocked at this and some were angry. But Nagai, although he sympathized with their reaction, continued his talk with quiet authority. By the end of it, the congregation fell into a deep silence. Interestingly, at the fortieth anniversary of the bombing, the comment was made about the difference between Hiroshima and Nagasaki in their response to the bombing: “Hiroshima is bitter, noisy, highly political, leftist and anti-American. Its symbol would be a fist clenched in anger. Nagasaki is sad, quiet, reflective, nonpolitical and prayerful. It does not blame the United States but rather laments the sinfulness of war, especially of nuclear war. Its symbol is hands joined in prayer.”

Soon after this event, Nagai was forced by his sickness to take to his bed. His spleen had swollen so much he had to lay on his back. He wanted to continue writing books, having already written several books of his experiences and reflections. His first book, The Bells of Nagasaki, recounted early experiences in the bombing and recalled the two bells that had been buried after the Cathedrals destruction, one of which had been dug up by Nagai and a friend. When this bell was rung on Christmas, it seemed a sign of renewal and hope for the city. This book had been widely read and was made into a popular movie. Another book was a scientific study of the effects of radiation. Despite its dangers, he saw the positive possibility of atomic energy. Although it was a challenge, he continued writing while bedridden, completing 20 books within the next six years of his life. One of them was about the details of the 26 sixteenth century martyrs of Nagasaki, which included St. Paul Miki whom he greatly admired. Another was about Jinzaburo Moriyama, the priest’s father who suffered the trial by ice and fire in the 19th century persecution. Nagai wrote haiku poems and did ink drawings as well.

Concerned for his children, Nagai turned his hut into a classroom for their education. Two of his books were for his children to help them after his death. With money from his writing, he built a library for the children. In the meantime, people of all kinds from all over the city and elsewhere came to him for counseling, for by now he was considered a wise and holy man who was able to provide encouragement and hope to people. He wrote an average of 5 letters a day responding to people. His advice was always positive and uplifting, giving people courage to deal with many sorrows and difficulties in a city and country torn with suffering.

Dr. Nagai was one of two Japanese whom the Japanese legislature proposed honoring as men who had rallied a demoralized nation. Communists opposed him and spread lies and vilification about him. However, the prime minister ordered an investigation and this completely vindicated him. So Nagai was honored as a national hero in December of 1949, and the minister of state, the governor of Nagasaki and the mayor came to his hut to give him his award.

By April of 1951, Nagai’s body was beginning to shut down. He asked to be put in the hospital so that the medical students could observe the last stages of leukemia. He was thinking of others up to the last. On May 1, he died, grasping a crucifix and praying “Jesus, Mary, Joseph.” The priest felt Mary had come to take him home. When the doctors did an exhaustive autopsy, they were dumbfounded that he had survived so long and been able to write his last two books. His funeral was May 3 at Urakami Cathedral where he had begun his Christian journey in 1932. 20,000 mourners attended. The mayor at the end of Mass spent 90 minutes solemnly reading aloud 300 messages of condolence, including one from Prime Minister Yoshida. Bells rang out the Angelus, echoed by a symphony of bells, all over the city from churches and Buddhist temples, and by factory whistles, horns, and boat sirens. The whole city stopped to honor their beloved Dr. Nagai.

This summary leaves out a lot of the inspiring details described in A Song for Nagasaki, so one should read the whole account. It is worth reflecting carefully about this man who in the midst of the horrors of this nuclear disaster and with his own body sick and injured, nevertheless thought only about whom he could help even though he had little to work with other than a heart of love learned from Jesus on the cross and years of prayer.

***

My second account is that of Fr. Gereon Karl Goldmann, OFM, who was in a Franciscan seminary in Germany in 1939 when World War II began. Coming from a family of strong Christian devotion, he had as an adolescent been in a Christian youth group under the direction of Jesuit fathers. When Hitler came to power, this group would compete with the Hitler youth group. These groups became antagonistic to the point of real battles. The Christian youth considered themselves soldiers for Christ so when police arrested them and put them in prison, they experienced it as an adventure and part of their role. Later when the Catholic boys had to attend a school where the director was a fervent Nazi, they became more aware of the threat to their country. When arrested, they declared in court that they, not the Nazis, were the new Germans and that Germany would be saved through Jesus Christ. Soon their group was proscribed, so they went on hikes to meet secretly and continue religious discussions, keeping their devotion to Catholic feasts. They were threatened with expulsion from school, but since they were good students, they were granted amnesty.

After graduation the students were sent to work camp. For the first time young Goldmann experienced the real world outside the protected environment he had grown up in, for now he was surrounded by men caught up in lives of vice and depravity. This proved, however, to be good schooling for his later experiences.

In the fall of 1936, Goldmann followed through on his longtime desire to be a Franciscan. A Franciscan missionary had come to his parish speaking of his work in Japan. So as a boy he was inspired not only to become a Franciscan but also to go some day to Japan. Now in the Franciscan seminary, he had finished his studies in philosophy by the summer of 1939 and was hoping to begin his courses on theology. But a day after he had completed his term, he and his fellow seminarians were inducted into the army, not by choice but by command. At first the military authorities looked down on them as weak and incapable of the rigors of military life. But they soon found out that the seminarians were in better physical condition than the other young German recruits, better educated and of strong character. Though given the hardest treatment and tasks, none dropped out, to the surprise of the officers. One of their challenges was the anti-Catholic opinions being expressed by the other soldiers, saying that a goal of the war was to abolish the Pope and the Church. Goldmann could not keep silent at this, and spoke out: “Are you aware that the leaders of Reich have signed a Concordat with the Catholic Church…that Christianity is one of the religions German is pledged to protect?” When they questioned him further, he said, ”Surely you are aware of the risk you are taking by thus expressing in the presence of so many witnesses sentiments so exactly opposite those of the government and Fuhrer?” They could say nothing to this, but his bold replies got him in trouble. But he felt his faith was in deep conflict with the Nazis and he could not be silent while so much hatred of the Catholic faith was being expressed. As a result, he was put through extra trials by the officers, but his strong upbringing and outdoor exercise enabled him to succeed in these. Then the officers began challenging the seminarians’ religion in the evenings. However, their in-depth classical education and two years of intensive philosophy training was used to prove the soundness of the faith.

A day came when the regiments were required to make an oath in honor of the Fatherland, however since the oath did not include the name of God, the seminarians considering that an oath without the name of God was no oath, they did not join the others in repeating the oath. The general noticed this and asked them why they did not join the others in swearing the oath and they explained their reason. The next morning they were called before the commanding officer, feeling certain they would be in trouble, but the officer told them that now they had the choice of joining the SS or remaining in the regular army. This amazed them. Goldmann raised the question about the oath, and he was told that their fuss over the oath gave the officers the assurance they would not break a meaningful oath. They were administered the earlier traditional oath with God’s name. The seminarians were then placed in the SS Bureau of Information, since it was clear they were intelligent men who could think for themselves. They were to be allowed to fulfill their religious obligations.

Although the SS has a deservedly negative reputation, Goldmann was able to use his position in charitable ways. When in the war in Belgium and France, he would warn the French citizens to bury all their gasoline because he was going to have to requisition it. Then later, he took only a small portion since most of it was hidden. In Paris, he would share food with the hungry French children from the abundant supplies of the German army. Since he knew French, he was able warn churches in advance of raids and tell them to hide their wine and holy vessels, and that priests should disappear to avoid being killed.

The fascinating account of Goldmann’s experience in the army is told in his book, The Shadow of His Wings. One important incident, however, bears relating here. On a leave of absence, he visited Sister Solano May who had been a foster mother to him since his mother had died when he was 8. She told him she had been praying for him for 19 years, and that he would now be ordained within a year. Goldmann objected that, according to Church law, he needed four more years of theology before he could qualify for ordination. She assured him that she and 280 sisters in her order had been praying for him, and since Scripture assured them that their prayers would be heard, he could be confident that he would be a priest in a year. She further pointed out that since it was the Pope who was responsible for the law, the Pope could dispense him from it, so when he was in Rome he must go to the Pope and ask him for his permission for ordination. “But I am not going to Rome,” Goldmann pointed out. “I have orders I must leave for Russia early tomorrow morning. With total confidence, Sr. Solano replied, “You will see. You will not have to go to Russia. You will see the Pope.” Goldmann thought privately this was all pious nonsense. But Sr. Solano told him further: “When you are in Lourdes, you must ask the Mother of God for help.”

The next morning Goldmann was on the train about to leave for Russia, when five minutes before departure, and auto drove up, took him off the train and detained him in some barracks. He had no idea what this was about. After three days, a commander presented him with an order from Berlin that he was to be transferred to another division in southern France. As it turned out, his post was close to Lourdes! This was the first sign that there might be something to Sr. Solano’s prediction. He was able to get to Lourdes and said some fervent prayers to Our Lady. When he reflected on the sudden change in his orders, he realized it must have come through one of the officers who was part of the conspiracy against Hitler and had asked him to deliver a message to contacts in Paris and in Rome. From the radio broadcast he was monitoring, he concluded the Allies were going likely to land in Italy. So he started studying Italian. In the meantime, his division received orders to go from France to Russia. However, once again orders came through to divert them south to Italy. Goldmann began to think Sr. Solano’s “foolish faith” was not so foolish after all.

The account of Goldmann’s experience in the battles in Italy are riveting and need to be read in his own words. It became clear that God had a protecting shield over him in several dangerous episodes. One in particular bears mentioning. After a busy day as a medic treating the wounded, he fell into a deep sleep but was awoken by a loud voice ordering him to get up and get to work. He asked the sentries if they had heard something, but they had heard nothing. Uneasy, he went back to sleep but was awoken twice again by the same voice, “Get up and work, it is past time.” So, not knowing what else to do, he set to work digging a fox hole. The soldiers around him made fun of him. But he got his driver, Faulborn, to begin digging as well. When the hole was big enough for him to lie down in, he suddenly heard above him 10 bombers circling the site, dropping 20 bombs. When the bombing was over, out of some 300 soldiers, Goldmann and his driver were the only survivors. Later he received a letter from Sr. Solano, asking him if he was all right because she had experienced great fear for him on this same night and had gone to the chapel to pray for him. Once again, Goldmann’s faith in her prayers was strengthened.

After months as a medic tending the wounded and dying, he felt keenly the desire to be able to provide confession, communion, and last rites to the Catholic soldiers who were without the sacraments. A friend challenged him to go to the bishop of the village where they were to request he send a priest to them. Goldmann was stirred to do this, but the bishop refused to provide him a priest. After several pleadings and a final demand. Goldmann, in desperation, took out his Luger pistol and held it up to the bishop’s face, telling him he had three minutes to grant him a priest or else he would force the bishop himself to go with them to bring the Blessed Sacrament to the wounded soldiers. The bishop turned pale with trepidation, but finally asked Goldmann to accompany him into his house, where he retrieved a document that permitted him to entrust the Blessed Sacrament into the care of a cleric for distribution. Since Goldmann was a Catholic cleric, the bishop wrote out a permission for him with his signature. Goldmann was elated and asked the bishop to forgive him for his rough treatment. Goldmann’s book relates many moving stories of wounded and dying soldiers to whom he was able to give the Eucharist, and the joy and solace this brought them.

In January of 1944, Goldmann found himself in Rome. With his faith in Sr. Solano’s promises strengthened, along with his growing concern to be able to minister to the dying soldiers, he decided to request an audience with the Pope, difficult as this would be. First he asked the general of the Franciscan Order if he could arrange an audience with the Pope for him. When asked why and was told he wanted to ask for Holy Orders. Then he was simply laughed at and refused since he didn’t have the requisite theology study. But Goldmann did not give up. He next went to the German Embassy where he delivered to a particular individual the secret message he had been entrusted with. The person then asked what he could do for him in thanks for his good service, so Goldmann asked for an audience with the Pope, explaining the need of the soldiers. Once again he was laughed at, but in the end a call was made to the Vatican and against all odds, his name submitted for an audience. Trembling at his own temerity, he proceeded to the Vatican and was led by an official to the waiting room. The prelate asked him what he wanted of the Holy Father, Goldmann mentioned two requests given him by others, then when pressed he mentioned his request for ordination. The prelate looked perturbed and instructed him to say nothing of this to the Holy Father since he hadn’t finished his studies. Silently praying to St. Therese of Lisieux to intercede for him, he finally came before the Holy Father. His conversation with Pope Pius XII should be read in its entirety in his account. Fatherly in his kindness with Goldmann, the Holy Father listened to his agony at soldiers dying without a priest to hear their confession and that nine German divisions had no priest. Goldmann also told him of his distributing Holy Communion, showing him the letter from the Bishop of Patte. Finally he told him of Sr. Solano’s 20 year prayer vigil, and her promise that when he got to Rome he would receive from the Holy Father a note authorizing ordination to the priesthood, and that despite being on a train to Russia, he had instead been reassigned, ending up in Rome. This last account finally convinced the Holy Father who gave him the precious note authorizing his ordination. Goldmann was overcome with joy.

Ordination was scheduled for January 30 but unfortunately his regimen was ordered on Jan. 24 to go to Cassino where British and American troops were on the offensive. The Germans were greatly outnumbered by the Allies in both men and equipment. The Germans ended up encamped at the top of a mountain in an old stone building. But when an inexperienced radio operator let their position be picked up by th British, the place was shelled mercilessly until there were only six soldiers left: Goldmann, his driver Faulborn and 4 wounded men. To avoid capture they were going to have to try to escape. Two of the wounded chose to stay and wait for the British. The other two with serious leg wounds chose to escape, so Goldmann half carried them as they stumbled down the mountain. Then they heard the marching enemy behind them, and they ran for their lives, shots falling all around them. Amazingly they were able to finally reach their own lines. They reported to the officers in charge what had happened. But when the officers heard they had left two wounded men behind, after checking with the general, they were told to go back and bring the other two. Goldmann explained that would be hopeless, the enemy was everywhere and they would either be killed or captured. Nevertheless, they were told to go, being provided with stretchers born by eight older men. After 30 minutes of travel, the old men said they would go no further as it was madness to walk straight into the enemy. So Goldmann said he would go alone. He crept forward, shaking with the fear of being shot at any moment. But suddenly the words of Psalm 91 came to him (“I will put my angels charge over you…”) After repeating the words of the psalm over, fear left him. He got down into the valley. The British soldiers above him didn’t see him, but they heard the sound of the stretcher bearers coming. Goldmann knew they would be shot by the British so he pulled out his Red Cross flag and waved it frantically. The English shouted “German Red Cross: don’t shoot. An English officer came to search him so he told him he had no gun and the other men had no guns. So they were taken captive but not shot.

When the British found out that not only was Goldmann a Franciscan in the SS but also that he had a letter from the Pope, they were astounded. So he was sent to Naples and interviewed by some high officers. The outcome of this was that he was flown to North Africa. After months in a cell in Algeria while investigations were going on, finally he was given the choice of being interned in a place where many seminarians were under the care of a Franciscan abbot. This was ideal, and while there was never enough food for the emaciated soldiers, it was relatively free and peaceful. It was here that, with the arrangement of the Abbot, Goldmann was finally ordained by the Archbishop of Algiers on June 24, the feast of St. John the Baptist. Sr. Soldano’s prayers and predictions were vindicated despite war and captivity: a German SS prisoner ordained by a French Archbishop. Truly God’s ways are marvelous. For two more months, the newly ordained Fr. Goldmann was able to celebrate Mass and to study while staying in the haven of this quiet monastery. But it wasn’t to last. Fr. Goldmann next was sent to Morocco, spending three weeks on an unpleasant and at times dangerous trip, facing hatred, criminality, filthy conditions and near death. The account makes for dramatic reading. His final destination was an infamous prison camp on the edge of the Sahara named Kaar-Es-Souk.

Prison camp experiences for Fr. Goldmann were a mix of blessings and great suffering. There were inspiring stories amidst appalling conditions, dreadful hate and cruelty. The camp was dominated by Nazis and their leader had a spy system that controlled what prisoners said and did. Those who voiced opposition to Nazism were severely beaten. So mistrust and paralysis pervaded. Fr. Goldmann was called in for an interview in which he firmly countered the Nazi arguments against religion and defended his right to say Mass and hear confessions, as this was allowed in Germany and the Nazis claimed the camp was German soil. When he told them of his years with the SS and that he was still technically attached to it, they were taken aback. But afterwards, a soldier who worked for the leaders quietly warned him not to go out at night alone as the Nazis were waiting to make him one of their “suicide’ cases, which was their practice with any dissenters. For awhile Fr. Goldmann was avoided by the men whom the Nazi leader had ordered to boycott him. But finally one, then three, then seven men came to speak with him. On Sunday, Fr. Goldmann set up a table for an altar in the courtyard and said Mass with these loyal followers. However, hundreds of men gathered around to observe what might happen. When Fr. Goldmann began the sermon he had shown to the interpreter for approval, he couldn’t resist the opportunity to speak to this crowd and extended his sermon for 30 minutes on the topic of Christianity and the German people. His Jesuit education, course in philosophy and experience with the SS poured out of him. Slowly this and further sermons he preached each morning began to have an effect. While the Nazis continued to oppose him with nastiness, other men were moved to return to their Catholic faith and some to be converted, so that the number of worshippers at Mass gradually grew. Some asked for more teaching, so a small school of theology, scripture and Church history developed. Christmas was a special breakthrough. The men built a small crib, prepared candles, brought music and decorated. Almost everyone came to the celebration except the most fanatical Nazis. After the Christmas Mass, Fr. Goldmann spent hours hearing confessions. Later men testified it was the best Christmas they had had, barren like the first birth of Christ but full of peace and joy. The number of believers steadily grew. The Nazis, of course, were furious and determined to stop this. They finally forbade everyone to speak to Fr. Goldmann. For two weeks he was alone. But finally one of the men leaving the camp told the French of what the Nazis were doing, so the French removed the Nazi leader and peace was restored for Fr. Goldmann. Impressively, the half-starved prisoners managed to build a simple chapel. Some French sisters sent altar linens, vestments, lamps and candles. God was building not only a physical chapel but a church of faith in the souls of the prisoners. Fr. Goldmann had to preach two sermons a day. Faithful men were praying for the conversion of their comrades.

When the war in Europe ended, the prisoners were allowed to serve in work camps. So Fr. Goldmann had a new assignment to serve the men at the work camps. During this time he experienced kindness from an order of French Franciscan sisters who demonstrated true Christian love that overcame the wartime enmity between French and German. The dramatic incidents of this period need to be read in detail. But one drama was particularly striking: the startling conversion of a notorious Nazi. Fr. Goldmann had had an earlier encounter with a very holy sister who had asked him to write down the name of the worst enemy of the church for her to pray for. So he gave her the name of this fanatical Nazi who was a terrible persecutor of the Church and of the French people. Three months later, this particular Nazi came up to Fr. Goldmann and asked to go to confession, saying he once had been a Catholic and wanted to come back to the Church. Fr. Goldmann knew his history and said it would not be a simple matter. He would need to do public penance for his many public wrongs. For months this notorious Nazi stood before the altar on Sundays as a penitent, and finally on one Sunday acknowledged before hundreds of men his guilt for his shameful history and asked for pardon. After this, he received absolution and Holy Communion. Fr. Goldmann found out later the good sister had been praying before the tabernacle for six hours every night for his conversion.

After the blessing of so much fruit from his ministry, a fellow priest warned him, there was certain to be a cross to follow. And so there was. One day, he was suddenly arrested and subsequently charged by a French court with being a criminal Nazi, with a list of specific accusations, including being a killer of the innocent and a former commander of Dachau. All of this was quite unbelievable and completely false. He suffered in a cold and filthy cell with no food. He became sick with high fever and lung infection. He was temporarily rescued by a doctor who was also a Franciscan. This was a fascinating story in itself. But when returned to the prison, he was informed the court’s verdict was that he was to be shot the following day. One of the officers kept asking him if he thought he would go to heaven, and finally just before he was taken out to be shot, this officer asked for confession. Moments later he heard the firing of shots in the courtyard. Then officers appeared and informed him an order had come from Paris to re-examine his case. The confession had delayed his execution long enough to be spared for this new decision. Later he found out about the Pope’s intercession.

Fr. Goldmann then had several weeks of reprieve in the work camps followed by more months in prison awaiting the final decision of his case. This period was interspersed with inspiring stories of holy nuns’ prayerful intercession for him, especially by a renowned Mere Monique ( a special story in itself) and support from local priests. Finally, a general came to tell him his case was closed. He was not who they thought he was, the commandant of Dacau. It was a case of mistaken identity. Eventually he was to find out how many sacrifices, prayers and miraculous incidents contributed to this final rescue.

Shortly thereafter, he was returned to Europe where he was detained several weeks in a camp for seminarians before being released to freedom. He returned to the Franciscan motherhouse in Fulda, which was both joyful and humbling, as he was simply considered a young Franciscan who had to complete his studies in theology. The prefect of studies gave him a plan of the necessary studies that he said would take three years to complete. However, with typical intensity, Fr. Goldmann, arising in the pre-dawn, spent long hours in study, took the examinations early, and completed the required study in nine months. Following this, he took some pastoral training and then spent a year as an assistant to a pastor in a parish in which he learned how different parish ministry is from prison ministry. Subsequently, he was assigned to teach young seminarians in Germany and Holland. During this period, he had the opportunity to visit a certain Sister Veronika who had been praying for his priestly vocation for 20 years and had been sacrificing for this during a long illness. He also visited in their monastery the Sisters of Perpetual Adoration who had responded to an urgent appeal for prayer when Fr. Goldmann was arrested and condemned to be shot. These faithful sisters once again impressed him with how the power of prayer had been behind both his early ordination and his rescue from execution. His whole ministry was the fruit of prayer, he concluded.

But he had not forgotten his dream of going to Japan, so he applied for the necessary visa. It was several years before it came through. Finally in January of 1954, he was able to go to Japan, and began a whole new epoch of his life as an energetic pastor of a parish in a poor suburb of Tokyo where he initiated many good works. (I have wondered if Fr. Goldmann heard about Dr. Nagai who was so widely known and admired in Japan at that time) This epoch is described in an Appendix titled, “The Ragpicker of Tokyo,” written by Joseph Seitz.

I have left out many fascinating details related in Fr. Goldmann’s account which you should read for yourself. In reflecting on the lives of Fr. Gereon Goldmann and Dr. Takashi Nagai, and the era of war in which they lived, I was struck by how the Catholic faith—when truly lived with dedication—surpasses any national or ethnic enmity. It unites any and all in a universal goodness, mercy, wisdom, and love. The stories of these two men also make clear the centrality of prayer as a source of the fruitfulness of their ministry. The presence of the sacraments in their experience is also a reminder of the unique and precious gift of this grace. My summary is only a hint of the inspiration you will find in reading their accounts.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics as we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image combines a photograph of Gereon Goldmann, uploaded by Moititestar49, and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, and a photograph of Nakashi Nagai , which is in the public domain. Both images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.