Suppose a man named Hutcheson lends ten pounds to a man named Smith. Then we might say, “Smith owes Hutcheson ten pounds.” Suppose that Hutcheson also teaches and aids Smith. Then we might say, “Smith owes Hutcheson gratitude/esteem/love.” Beyond Hutcheson, Smith might feel that he has been taught and aided by humankind generally, and Smith might say, “I owe humankind love.” These are all is sentences.

Suppose a man named Hutcheson lends ten pounds to a man named Smith. Then we might say, “Smith owes Hutcheson ten pounds.” Suppose that Hutcheson also teaches and aids Smith. Then we might say, “Smith owes Hutcheson gratitude/esteem/love.” Beyond Hutcheson, Smith might feel that he has been taught and aided by humankind generally, and Smith might say, “I owe humankind love.” These are all is sentences.

Adam Smith himself says:

If I owe a man ten pounds, justice requires that I should precisely pay him ten pounds, either at the time agreed upon, or when he demands it. What I ought to perform, how much I ought to perform, when and where I ought to perform it, the whole nature and circumstances of the action prescribed, are all of them precisely fixt and determined. (TMS, 175, italics added)

Here Smith goes naturally from “owe” to “ought.” That ought derives etymologically from owe is confirmed by both the Oxford English Dictionary and the Online Etymological Dictionary. The latter, in the ought entry, says that ought came from the Old English word agan, meaning “to own, possess, owe.” Specifically, ought comes from its past tense, which is ahte. In fact, in the owe entry, it indicates that until the 15th century the past tense of owe was oughte, which then was replaced by owed, while oughte developed into ought. Further, in the ought entry, it says that ought “has been detached from owe since 17c., though he aught me ten pounds is recorded as active in East Anglian dialect from c.1825.”

I imagine the following dialog between an Interviewer and Adam Smith:

Interviewer: You say you ought to pay Hutcheson ten pounds. What do you mean by that?

Smith: I owe him ten pounds, and so I have a duty to him.

Interviewer: Yes. But where is the ought?

Smith: Well, to say that I have a duty to him implies that, unless other and greater duties say otherwise, I ought to meet that duty.

Interviewer: But what does it mean to say that you ought to meet your duties?

Smith: Well, I owe it to myself to meet the duty to Hutcheson, and so I have a duty to myself.

Interviewer: Fine. But what does it mean to say that you ought to meet the duty to yourself.

Smith: Well, I owe it to myself to meet that duty, and so I have a duty to meet that duty.

Interviewer: Fine! But what does it mean to say you ought to meet the duty to meeting that duty?

Smith: Well, we have supplied a spiral without end.

Interviewer: I see that. And that means we haven’t gotten to the bottom of it—in fact, that we won’t get to the bottom.

Smith: I should only counsel that you make yourself accustomed to that. Should it trouble you so?

Interviewer: Well, in my schooling, I learned that ought statements are different than is statements. I recognize that your “owe” statements are is statements, so I am trying to find the differences in ought statements.

Smith: I see no necessary difference between some two sets of statements so characterized. What sort of schooling is practiced where you come from?

Interviewer: I have attended the best universities of my times and been taught by the best authorities. What’s more, I have studied the best authorities from the time of John Neville Keynes. And they all seem to agree on this matter.

Smith: I see. Well. One authority of your times, McCloskey, says: “Economists do not pay enough heed to moral questions, hiding behind the sophomore philosophy of normative/positive.” Is not she, or any of the many authorities she shows saying much the same, one of the best?

Interviewer: No, she’s not. The best authorities find her provocative, but disagree with her on many things.

Smith: Allow me another stroke to gratify your animus against “ought.” Where I write:

Nature, accordingly, has endowed [man], not only with a desire of being approved of, but with a desire of being what ought to be approved of; or of being what he himself approves of in other men. (117)

I am saying each of us, such as James, is endowed with one or both of the following: (a) a desire of being of such character that he perform what is owed to God or to a God-like allegorical being that some call Joy; (b) a desire of being of such character that would be socially approved of in a society in which people owed to themselves duties like those of which James approves. (Let me point out that, while (a) and (b) are distinct, they go naturally together, since the only way James has to approach God/Joy is by heeding what he himself approves of in other men.)

Now I have expelled “ought” and instead use “owe,” which you allow is an is. There is no important difference between the passage from page 117 of my book and the exposition that follows, though the first be more natural.

Interviewer (showing wonder and surprise): Hmmm. You say some provocative things—that I can say positively. But I ought to let you go. Thank you, Dr. Smith.

Smith: Maybe you ought or maybe you oughtn’t. In any case, thank you for your visit.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

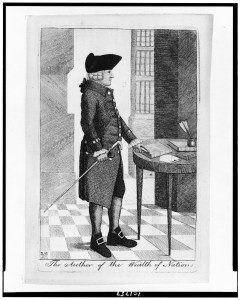

The featured image is an engraving of Adam Smith created in 1790, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.