The Church has disavowed her ancient usurpations of the political. It remains for the Catholic to stop imposing these duties on her. Who is to say, once she has been thus unencumbered by the vain expectations of her own children for the war-leadership she should not provide, that she will not once more glow with the sanctity and miracles that distinguished her auspicious beginnings.

On October the twenty-ninth of the year 1268, Christendom bore witness to an outrage perpetrated on the Piazza del Mercato in Naples. A beautiful and charismatic teenager, dressed in black in anticipation of his own burial, was beheaded by the executioner of Charles of Anjou, himself a prince of the Capetian Dynasty and the younger brother of King Louis IX of France. Charles had invaded Italy at the behest of the Roman Church and, as its champion, had seized the Kingdom of Sicily from the deceased emperor’s bastard son (Manfred) on the field of Benevento (1266). And now, by executing this boy, Charles believed that he had finally settled the disputed Crown of the Two Sicilies upon his brow. The judges and executioner were Charles’ men, but behind them was the pope, who allegedly urged Charles on to this act—ruthless even by the standards of the day—with fierce imprecations: Vita Conradini, mors Caroli; vita Caroli, mors Conradini! (“Conradin’s life spells your death; your life requires his death!”). The boy’s crime? He had led an army of imperial loyalists from Germany across the Alps—to Rome, where he scattered the pope and his court in flight and received an emperor’s homage from the people there—and thence southward, where he aimed at reclaiming the Kingdom that had come to him by right of inheritance. The official indictment of Conradin read out on the piazza charged him as a bandit and rebel. But the boy’s true crime—for which Pope Clement IV urged Charles to bring him to the headsman’s block—was in his blood: for Conradin was the grandson of Emperor Frederick II, Stupor Mundi, and the last representative of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, that “brood of vipers” to whose destruction the papacy had dedicated itself for the past thirty years.

On October the twenty-ninth of the year 1268, Christendom bore witness to an outrage perpetrated on the Piazza del Mercato in Naples. A beautiful and charismatic teenager, dressed in black in anticipation of his own burial, was beheaded by the executioner of Charles of Anjou, himself a prince of the Capetian Dynasty and the younger brother of King Louis IX of France. Charles had invaded Italy at the behest of the Roman Church and, as its champion, had seized the Kingdom of Sicily from the deceased emperor’s bastard son (Manfred) on the field of Benevento (1266). And now, by executing this boy, Charles believed that he had finally settled the disputed Crown of the Two Sicilies upon his brow. The judges and executioner were Charles’ men, but behind them was the pope, who allegedly urged Charles on to this act—ruthless even by the standards of the day—with fierce imprecations: Vita Conradini, mors Caroli; vita Caroli, mors Conradini! (“Conradin’s life spells your death; your life requires his death!”). The boy’s crime? He had led an army of imperial loyalists from Germany across the Alps—to Rome, where he scattered the pope and his court in flight and received an emperor’s homage from the people there—and thence southward, where he aimed at reclaiming the Kingdom that had come to him by right of inheritance. The official indictment of Conradin read out on the piazza charged him as a bandit and rebel. But the boy’s true crime—for which Pope Clement IV urged Charles to bring him to the headsman’s block—was in his blood: for Conradin was the grandson of Emperor Frederick II, Stupor Mundi, and the last representative of the Hohenstaufen dynasty, that “brood of vipers” to whose destruction the papacy had dedicated itself for the past thirty years.

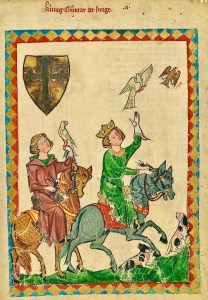

I confess that I often think of Conradin’s death—whether as it was conjured brilliantly by Steven Runciman in his Sicilian Vespers (1958) or as it is depicted so strikingly in a fourteenth-century manuscript of Giovanni Villani’s Nuova cronica contained in the Vatican Library (MS Chig. L.VIII.296, f. 112v). As Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) did, I ruminate on this last tragic act in the high medieval drama of the death-duel between papacy and empire from beyond the threshold of papal monarchy’s highwater mark—when the vicar of Christ held the field amidst the ruins of the House of Hohenstaufen, for the pulling down of which he had spared not one measure of his claimed plenitude of power, though without realizing, as of yet, the fierce price that he had paid: all of the spiritual capital—treasured up so slowly for centuries by his predecessors—expended in a matter of decades through an incessant spate of excommunications, anathemas, fulminations, crusades, and depositions. The papacy’s spiritual bankruptcy was to be revealed a few decades later, in the sorry transactions between King Philip IV of France and Pope Boniface VIII. We, like Dante, can reflect on the doomed mission of Conradin in the light of Unam sanctam (1302), the Outrage of Anagni (1303), and the beginning of the Babylonian Captivity of the papacy (1309). But whereas in Dante’s day the feud between papalist Guelfs and imperialist Ghibellines still broiled throughout northern Italy—the latter eventually winning an older and wiser Dante over to the emperor’s cause—today, among Catholics, there are no Ghibellines and the Guelfs hold the field unchallenged. But I am still haunted by Conradin’s ghost.

Many of us are. No, this is not some bizarre legitimist fetish for a dynasty or the confessions of a crank designed to render him innocuous when politics come up at cocktail parties (“Don’t worry, I’m a monarchist, I don’t have opinions about this”). This isn’t about the Hohenstaufen—they are dead. This is rather about a political order for Catholics, outside of which Catholics cannot be fully human. This is about a cosmic vision—the shattered remnants of which we survey at Canossa, Tagliacozzo, and Anagni—of necessary duality. Medieval political theorists and theologians spoke of “two lights” or better yet, of “two swords”—Christ Himself had said that two swords were sufficient (Luke 22:38). Justinian and his lawyers spoke of symphonia—a divinely inspired concert carried on by King and Priest; canon lawyers of the High Middle Ages were fond of the image of the “the [sacerdotal] sun and the [royal] moon.” By no means were all of these theories identical in terms of the way they articulated the relationship between “these two things” (Pope Gelasius I’s haec duo), and the devil was in the details, but what they all pointed to was duality: a balance between the political and the ecclesiastical, between flesh and spirit, between the Masculine and the Feminine.

Translated into Straussian terms, this is the dialectic between philosophy and politics, each with its own inexorable demands. So long as there was a counterpoint to papal monarchy in universal empire, this dialectic remained at least possible as a duality in tension. But the medieval history of the struggle between empire and papacy reveals a series of usurpations of the former’s functions—in the terms of the medieval theorists themselves “the sword of bloodshed”—by the latter. In the short term, this absorption of the political order within the ecclesiastical order enabled the papacy to triumph over its rival and to redefine political legitimacy in its own terms. But in the long run, the pope’s use of political instruments in the service of aims that, however justified by theological reasons, remained transparently political (i.e., territorial domination in Italy), ended up destroying his credibility in the eyes of Christendom. What followed thereafter was calamitous for the social organism of Christendom. Yes, the Protestant Reformation was made nearly inevitable by the papacy’s failure to respect the integrity of the political order (early Lutheran and Anglican woodcuts with their many depictions of the humbling of imperial Germany by sacerdotal Italy bear witness to this), but the more disastrous result followed even more quickly. When disputes arose between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France regarding taxing the clergy for state purposes, and the pope attempted to have his way by drawing the usual weapons from the same arsenal, the king and his councilors remained distinctly unimpressed. The root of the French Capetian dynasty’s ideological power did not run through Rome as had the emperor’s title and when Boniface had made his own violation of the ancient diarchy between king and priest sufficiently clear—a violation rendered more flagrant by the undoubted textual manipulations of Philip’s lawyers—what ensued was the scene that played out at Anagni, when Philip’s thugs manhandled the pope and left him in a state of hysterical apoplexy he did not long survive. What followed thereafter was a dramatic reversal: the attempt by royal power to embody within itself the fullness of the cosmic order. Royal and imperial courtiers, such as Pierre Dubois and Marsilius of Padua, now imagined the Church as a department within a totalizing state.

What saved the autonomous Church, ironically, were the upheavals and revolutions of modernity that brought down kings and their altars and saw the triumph of liberal ideology, which imposed an eternal peace on the struggle between kings and priests by outlawing the former and exiling the latter to the realm of conscience, private profession, and voluntary association. No matter how stupendous the edifice of papal monarchy in Ultramontane fantasy, equipped with all the trappings of infallibility and canonical supremacy, it is to the liberals innocuous insofar as it remains, for all its gaseous expansiveness, immaterial: it is all private belief that can be professed or discarded by the individual conscience without any material consequences. It is a castle in the clouds.

Clouds invite useless daydreaming. Sometimes gaseous formations look like Kingdoms. Now behold vital young Catholics, particularly (but by no means only) Catholic men who find themselves in a frustrating situation. In the world that liberalism has made, we are entitled to construct our own identities—so long as these don’t hurt anyone else. Perceiving themselves surrounded by evil, they long to equip themselves for the struggle by discovering what they are. Naturally, they reach for their Catholicism; then they weave around themselves a cocoon of devotions and liturgical forms; they nurture obedience and deference to spiritual superiors; they commit to the “good behavior” required of them. They yearn for father-figures with whom to identify themselves, and look with expectation to their priests, bishops, and even the pope. But soon they begin to look around and see—at their parish and its recreations—and a sneaking suspicion begins to grow in their minds. Spend any amount of time talking to most of the clergy (with honorable exceptions, of course) and the women who dominate the parish council, and then the realization dawns: this is not a place for you. This is a feminine space. Catholics who look to the episcopate and papacy for virile leadership are frustrated; they must determine whether to spend their days engaging in mental gymnastics in behalf of the hierarchy or simply become numb to it all. You will see these young men in gymnasia across America working off their frustrations and finding solace at last in the Church of Hoist.

Do not misunderstand me. The cloth is still worn by many good servants of God who, left to themselves, would provide excellent role-models for young men. Nor is the episcopate or the papacy itself the problem now. We must not blame priests for simply being what they are. (And the Church herself has suffered immensely in undermining imperium—not because it lost muscle to enforce her orthodoxy, but rather because she lost credibility by usurping political functions—an approach that the churchmen have since disavowed). Much as I sympathize with the frustrated, in truth it is they themselves who are responsible for their own suffering. For it is they who demand from the priest things that the priest cannot give. They look to the clergy to affirm their own deep-seated desires to become terrible in the sight of the wicked and “to bear not the sword in vain” as the minister of God’s vengeance (Rom. 13:1-7). And all of this—temporal justice, corporeal punishment, warfare, bloodshed—belong to the political order, not to the Church. But as Aristotle taught, the only human creatures that can abide outside of the polis are, in truth, either sub-humans or gods.

Some men and women are called to become gods and to live the life of philosophers and angels. They can be communists because they have renounced their flesh; they can be pacifists because they have renounced their wills; they can even be martyred since they have hated their very lives (cf. Lk. 14:26). But civilization cannot abide by these terms. So long as men marry and are given in marriage; so long as they bear and rear children; so long as they store up for those children earthly treasures liable to theft and corruption, the demands of politics remain inexorable. In his decretal Venerabilem (1202), Pope Innocent III (r. 1198-1216) explicitly disavowed any desire to usurp the right of princes—and well he should, vicar as he was of the God Who Himself had recognized the rights of Caesar (Matt. 22:21).

This is where the integralists go wrong. The subjugation of the political order to a caste of celibate men who profess poverty and have renounced their claims on the earth is totalitarianism worth resisting to death. Catholics are mistaken when they look to their churchmen for leadership and solutions to this-world problems. That isn’t their job: their eyes are fixed (or should be fixed) Elsewhere. The sword of bloodshed does not belong to the priest. What we could use is a resurrection of a new Ghibelline mindset that restores to Caesar his rights to guard earthly borders, material property, and the children of our flesh; a neo-Ghibellinism that asserts the legitimacy of the political, on its own terms, as inherent to our very nature; a new vindication of the Gelasian dualism that urges a mutually-beneficial dialogue between politics and philosophy while maintaining the purity of the priest and the king. Perhaps then Conradin will sleep at last.

The Church has disavowed her ancient usurpations of the political. It remains for the Catholic to stop imposing these duties on her. Who is to say, once she has been thus unencumbered by the vain expectations of her own children for the war-leadership she should not provide, that she will not once more glow with the sanctity and miracles that distinguished her auspicious beginnings—those celestial signs that can even impress themselves on the minds of earthly kings and persuade them to better paths. This was the suggestion, at any rate, of Frederick II, when, harried on all sides by the insurrectionists stirred up against him by the pope, he ruminated on those priests of times bygone, “who used to see angels, to shine resplendent with miracles, to cure the sick, to raise the dead, and to subject kings and princes to themselves by holiness, not by arms.”

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is Codex Manesse, fol. 7r, Konradin von Hohenstaufen (“König Konradin der Jüngere”) bei der Jagd mit Falken, dated between 1305 and 1340. This file is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.