ANOTHER day, another story about young people and their mental health, with the BBC running a news piece about students feeling ‘let down’ by universities which fail to support them properly.

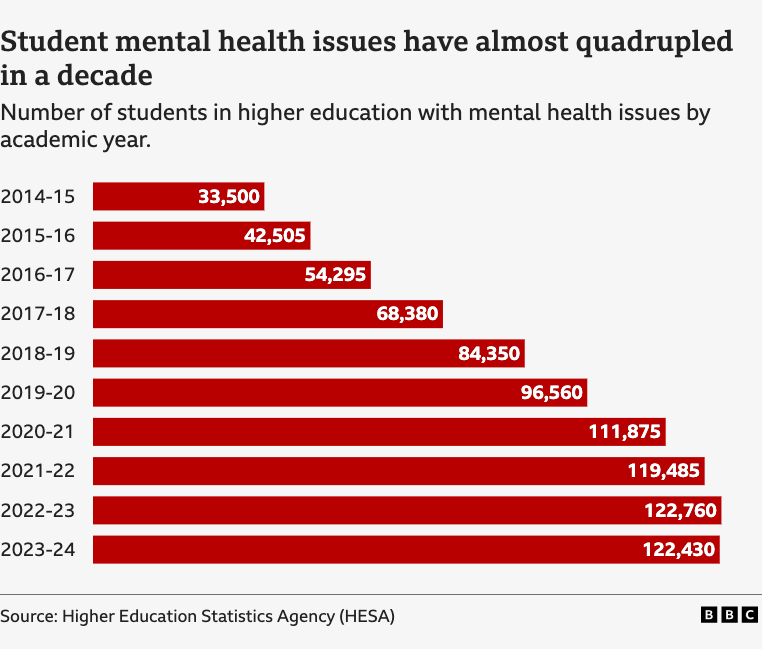

The article discusses two female students with diagnoses of (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)/autism and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) who complained that the institutions where they were studying didn’t help them enough with counselling or extending deadlines. It goes on to outline the hugely increasing number of students reporting a mental health condition, which has quadrupled in the decade to 2023/24, with the majority being women.

The latest figures from the NHS, released in June, reveal that one in four young people aged 16-24 in the UK is suffering from a mental health condition. Again, many more young women report having a mental illness than men, with more than 31 per cent in this age group suffering from ‘common mental health conditions’, which include generalised anxiety disorder, depressive episodes, phobias, OCD and panic disorder.

The proportion of people reporting ever having self-harmed has also quadrupled since the year 2000.

Young people also report more severe mental illnesses than older people, which is reflected by the huge increase in claims for Personal Independence Payments (PIP) from young adults who say they cannot work due to their disability – nearly half of these payments are now paid out for mental health conditions.

PIP can offer a maximum of £749.80 every four weeks. It’s not means-tested, so a person’s income, savings, or employment status don’t affect eligibility, nor is eligibility determined by diagnosis alone; some people qualify before they even have a defined diagnosis – and nearly 80,000 receive PIP for ADHD.

The latest figures released on July 23 by the Department for Work and Pensions (DwP), show that one in ten people of working age is claiming a sickness or disability benefit. The number claiming health-related benefits with no requirement to work has increased by 800,000 since 2019/2020 – a rise of 45 per cent, whilst the number claiming PIP is likely to double this decade from two million to 4.3 million.

The Government is projected to spend £70billion a year on health and disability benefits by the end of the decade, with PIP spending alone almost doubling to £34billion annually by 2030.

Keir Starmer had planned reforms including changes to eligibility criteria and increased employment support, which were expected to save taxpayers £5billion a year, but he has now U-turned on the PIP reforms following a rebellion from Labour backbenchers who believe it’s inhumane to scrutinise who is receiving state handouts.

Clearly this cannot go on; we cannot continue to have more than half a million 16-to-24-year-olds economically inactive due to ‘mental health’ conditions, especially considering the birth rate is currently the lowest ever recorded in the UK.

Who will pay the pension bill for an increasingly ageing population? No chancellor is ever going to be able to balance the books when a substantial proportion of physically able young adults not only don’t work, but have no intention of ever doing so. Recent analysis of the cost of the state pension suggests the Government may need to withhold payments until the age of 80. This should be a huge cause for concern.

How do Labour’s back-bench MPs believe that taxpayers can continue to fund the welfare bill when a large proportion of healthy young adults won’t work and not enough children are being born to replace them? There is no magic money tree.

While it’s right that those genuinely suffering with mental distress are no longer stigmatised, we seem to have swung so far the other way that it’s now unacceptable to question the mental wellbeing narrative – after all this industry is a big money ticket. The UK mental health market reached $14.78billion in 2024, and is projected to reach $19.12billion by 2033, driven by ‘the increasing cases of mental health issues, implementation of government policy initiatives and funding to address mental health issues, and rise of digital platforms for therapy and counselling’.

As outlined by counsellor and author Lucy Beney in the latest report by the Family Education Trust (FET), Suffer the Children, which examined mental health initiatives for children in schools: ‘We also need to have a clear understanding of what is meant by “mental health”, and indeed “mental illness”.’

Increasingly, distress is viewed through a diagnostic, ‘medicalised’ lens when frequently young people are in fact reacting normally to abnormal situations. It would be more unusual if they did not react when their lives fell apart, when they encountered life’s challenges or when they suffered the consequences of early adverse experiences.

Rather than examine why so many are in distress, the response to the most recent figures is to provide mental health support through an NHS App with AI-driven support and plans for 85 new mental health emergency departments.

Given that too much time online and lack of socialisation is a common driver of depression and anxiety, it is hardly a wise move for the Government to hand over such a responsibility to a computer-generated counsellor. This is especially worrying considering that X’s latest chatbot Grok has just launched two new ‘companions’, or AI characters for users to interact with — including a sexualised blonde anime bot called Ani that is accessible to users even when the app is in ‘kids mode’.

Labour also plans to install a mental health professional into every school, but as Suffer the Children points out, there is a lack of regulation and oversight in the therapeutic counselling industry and many counsellors today no longer see focusing on their client, and exploring their client’s world, as their primary role. Instead, the approach is to view the person through the ideological lens of the oppressed versus the oppressors, heteronormativity, victimhood and intersectionality.

While ministers insist that the focus on mental health campaigns in schools is the only way forward to stem the tide of children’s increasing emotional distress, the most pressing question must be – are these measures actually improving the wellbeing of children and young people? The short answer, in general terms, must be no.

At best, there are mixed results on the success of psychological interventions delivered in school settings and the number of children being diagnosed with a mental disorder gets worse every year. Yet no politician has raised the fact that a good deal of this increase could be down to both social contagion and family breakdown.

A 2009 Government Evidence Review concluded that ‘family breakdown in all its forms is strongly associated with poor mental health in adults and children’.

Children suffering the consequences of family breakdown are 50 per cent more likely to fail at school, have low esteem, struggle with peer relationships and have behavioural difficulties, anxiety or depression. The Centre for Social Justice advised the DwP to ‘consider how relationship support for parents can be provided to prevent potential mental health problems before they occur’.

This was more than 16 years ago – yet more families than ever are reaching breaking point.

The FET report concludes: ‘It would appear that, as a society, we have a very large, complex and growing problem on our hands, and very little idea of how to solve it. A less charitable view is that we lack the courage or conviction to look beneath the surface of the “mental health crisis” and address some difficult and controversial aspects of the way we live today, and the impact that this is having on our children.’

With broken families and fractured communities, children have looked for a sense of identity elsewhere, finding community and attention through being diagnosed as neurodiverse or having a label such as ADHD. Social media sites such as TikTok have online groups dedicated to self-diagnosis of such disorders and popular ‘sickfluencers’ teach their followers how to apply for benefits and PIP payments.

Rather than encouraging isolated children and teenagers to look inward through mindfulness techniques, we need to encourage them to look outwards, beyond themselves and their own narrow interests.

Employment or volunteering can provide a sense of purpose and social interaction which can improve mental health. Creating community by a shared pride in our country would help to give young people a renewed identity in what it means to be British.