Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of Macbeth” reminds us at a visceral level that the supernatural and the natural worlds are interwoven in a matrix of good and evil. When Macbeth dabbles in the occult, he lets loose the lords of darkness.

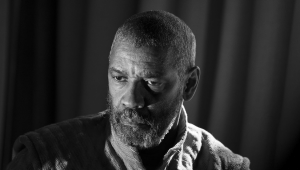

A stark, new cinematic take on Macbeth is Joel Coen’s 2021 adaptation The Tragedy of Macbeth. With Denzel Washington as the troubled thane and Coen’s wife Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth. Suitably filmed in black and white, Coen’s vision uses simple sets and staging to imply the austerity of Shakespeare’s Scottish setting while retaining a theatrical atmosphere. The Coen brother’s films are always rich experiences of visual storytelling that usually operate within the vocabulary of traditional filmic genres while renewing them within.

A stark, new cinematic take on Macbeth is Joel Coen’s 2021 adaptation The Tragedy of Macbeth. With Denzel Washington as the troubled thane and Coen’s wife Frances McDormand as Lady Macbeth. Suitably filmed in black and white, Coen’s vision uses simple sets and staging to imply the austerity of Shakespeare’s Scottish setting while retaining a theatrical atmosphere. The Coen brother’s films are always rich experiences of visual storytelling that usually operate within the vocabulary of traditional filmic genres while renewing them within.

Their re-make of True Grit, for example, looks and feels like a traditional western, while the brilliant cinematography and clever writing refresh rather than simply repeat the conventional expectations. Similarly, Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth echoes the look and style of classic film noir. The high windows, long shadows, gothic sets, skewed angles, and narrow points of view are all there—even the femme fatale takes a bow. (Indeed, Lady Macbeth may be the archetype of every subsequent femme fatale). But this film noir is not Raymond Chandler, but William Shakespeare.

Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is not only film noir in cinematic style, but also in the obvious themes of murder, mayhem, paranoia, and betrayal. Coen also picks up on a powerful image system already in Shakespeare’s play and uses it with insidious intent. An “image system,” for those not in the know, is a recurrent image in a film that subconsciously carries the theme and characterizations. An image system is like a symbol, but it operates on an even more subtle level than a symbol. Great filmmakers weave in the image system and sneak it past our conscious minds so that it has an even greater effect—imprinting the film’s themes in the emotional, chthonic level of our heart and mind.

The image system in Coen’s film are the birds. From the opening shot with kites (the birds, not the toys) wheeling above, to the final shot of flocks of ravens, the birds provide an ominous presence. Coen is thus referencing Shakespeare himself for birds make frequent, and often noisy, appearances in Macbeth. There are sparrows, eagles, ravens, ‘martlets’ (house martens), owls, falcons, crows, chickens, kites, ‘maggot-pies’ (magpies), choughs, rooks, and wrens.

In Coen’s film, as in Shakespeare’s play, the birds croak, breed, haunt, shriek, scream, clamour, tower, hawk, kill, wing, rouse, fight, swoop, and, in the case of a little ‘howlet’ missing its wing, provide an ingredient ‘for a charm of powerful trouble’ brewed by the weird sisters. This owl is not the chubby feathered friend of Christopher Robin. In the medieval and Renaissance world owls were widely detested. They were considered unclean, their hooting ‘betokening death’ if heard at night. They were, as a result, often captured, killed, and nailed to doorposts to ward off bad luck.

Kites were similarly loathed and systematically culled. They were considered vermin in Shakespeare’s day. A “ravishing fowl” that “lies in wait” for its victims, there are records of kites attacking babies left unsupervised, as Shakespeare alludes to in The Winter’s Tale: leaving the ‘poor babe’ Perdita to her fate, Antigonus asks that ‘Some powerful spirit instruct the kites and ravens / To be thy nurses!”

Ravens, rooks, and crows were birds of horror. It was noted that they scavenged flesh and fruit “indifferently”, and they were believed to “warneth what shall fall” if one could read the signs correctly. It is this superstition that Macbeth refers to when he muses: “Augures, and understood relations, have/ By maggot-pies, and choughs, and rooks brought forth… the secret’st man of blood”.

When we first hear of Macbeth, he is described as an ‘eagle,’ but soon he and his wife are almost exclusively accompanied by descriptions of ominous scavenging birds: Lady Macbeth claims “The raven himself is hoarse, That croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan” into the castle, and shortly hears “the owl that shrieked” the King’s long goodnight’. These aren’t just figments of the Macbeths’ imagination: Lennox describes how “the obscure bird”, or owl, hidden in darkness, “Clamoured the livelong night”, and an old man insists that, a week earlier, a lowly “mousing owl” killed a noble falcon in flight. [*]

Coen’s nod to film noir and use of the avian image system also reminds one of Alfred Hitchcock’s later film The Birds. While Shakespeare (and Coen) allow the birds to function below he surface as omens and threatening signs of terror, Hitchcock brings them into the foreground so they become actual instruments of terror. In Hitchcock’s nightmare birds gather with no apparent reason in a small town eventually attacking the residents on a killing spree.

Coen signs this debt to Hitchcock in several scenes where flocks of ravens besiege Macbeth, attacking an open window or whirling in a frightening and irrational flurry of feathers, claws and beaks. Indeed, the weird sisters themselves are clad in black, wing-like cloaks, and in their second scene are perched in the rafters like terrifying vultures.

The effect—in Shakespeare, in Coen, and in Hitchcock’s horror classic—is to remind us at a visceral level that the supernatural and the natural worlds are interwoven in a matrix of good and evil. When Macbeth dabbles in the occult, he lets loose the lords of darkness. The natural is twisted by the un-natural forces of evil so that the whole created order is undone: even the birds of the air—usually harbingers of spring and bright friends of angels—become dark denizens of Dunsinane, the castle of doom.

[*] I am indebted to an anonymous article on the website of Macbeth the film for the information on birds in the previous paragraphs.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is courtesy of IMDb.