We marked last month’s fifth anniversary of the imposition of lockdown on the British people by republishing some of our articles from that week. While the mainstream media were baying for stronger and longer restrictions, we were almost alone in criticising lockdown and showing that it would have catastrophic results for zero benefit. We continue to remind readers of the weeks – and the insane policies imposed on us – that followed. Today’s article, ‘An awful lot of people cannot afford a lockdown, ministers’, appeared exactly five years ago on April 11, 2020.

SO THE lockdown continues. Why exactly is unclear. Dominic Raab said on Thursday that ‘the measures will have to stay in place until we clearly have the evidence that we have moved beyond the peak’.

This is a change from previous policy. Until now we have been told we were flattening the curve to ensure that the health service can cope with peak demand and save lives. This did not require moving ‘beyond the peak’ before easing restrictions, just flattening the peak to a manageable level.

What Raab surely should have been talking to us about is health service capacity and projections of whether it will now be sufficient. Have we now slowed the virus enough and boosted the health service enough to mean it won’t be overloaded? If so, we need to get the lockdown lifted, because it is insanely costly. The government and their advisers act as if they can afford to add extra weeks of lockdown just to be on the safe side. Maybe they can afford it personally but an awful lot of people cannot. The lack of urgency within government to get this thing over is palpable and deplorable.

Bizarrely, the government still seem to be citing the reported cases statistics as an indication of the number of infections and the spread of the virus, despite this having been thoroughly discredited by many experts.

At least, though, chief scientific officer Patrick Vallance did admit for the first time that the virus has probably already spread to far more of the population than is reflected in the reported cases. He also claimed, however, that most of the figures that have come out for this in different countries so far are ‘low single digit percentages’. It’s unclear what his source is for this, as in Germany it looks to be around 10 per cent, if the widespread testing they have done is anything close to representative of the general population.

Vallance also claimed that asymptomatic cases ‘could be around 30 per cent’, despite that the three main studies on this so far, in Vo, Italy, Iceland and the Diamond Princess cruise ship, all show between 48 and 75 per cent asymptomatic cases. It’s a shame these briefings don’t come with references as the government at times seem to be reading different studies from the rest of us.

As far as I can gather, the basic issue now is a fear that if lockdown is relaxed the infection rate will shoot up again and overwhelm the health service. At the heart of this are two very questionable beliefs that are held almost as articles of faith by those currently managing the crisis. The first is that the Wuhan coronavirus if left to itself would very quickly spread to almost the entire population, leaving a large number of people dead, many of them avoidably so had they had access to life-saving medical attention. The second is that the severe lockdown we have imposed is effective in preventing this from happening.

Both of these beliefs bear little relation to the facts. Since, as looks likely, the Wuhan virus had been in many countries for weeks before it was detected, and lockdowns were imposed very late in its spread, there is little reason to think such measures bear much responsibility for limiting its growth. The lack of any clear relationship between the severity of lockdown measures in a country and the impact of the virus further supports this point.

What seems more likely is that for reasons inherent in the behaviour of the virus it does not spread to everybody, or everybody in one go, just as only 17 per cent of those living in close quarters on the Diamond Princess tested positive for the virus and only 15 per cent of the populations of Gangelt in Germany and Shenzhen in China were infected.

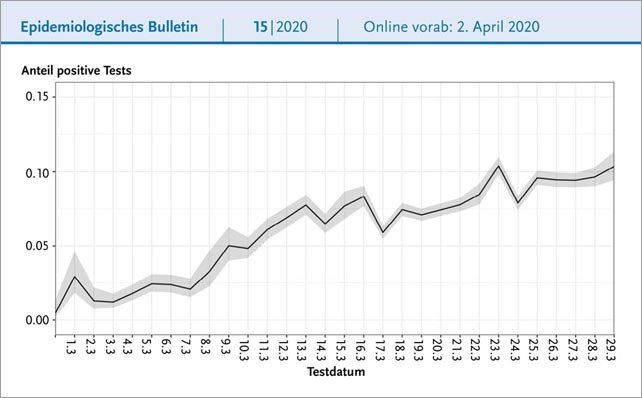

This would explain why the proportion of positive tests typically increases only slowly and tends to have a limit (different for each country) rather than continuing an exponential explosion until everyone has it. In Germany’s case that limit is around 10 per cent, and the slowing of the rate of increase (beginning on 13 March) occurred well before any lockdown measures were put in place (on 22 March) or had chance to make a difference.

Content/Infekt/EpidBull/

Archiv/2020/Ausgaben/15_20.pdf?__blob=publicationFile

The problem with believing that only the strictest lockdown measures are what are standing between you and a catastrophic spread of the virus is it leaves you fearing that you cannot lift them at all until you have an effective treatment or vaccine. After all, if only 10 per cent of the population has had it so far, and you believe that the only thing stopping the other 90 per cent catching it in short order (and at least one per cent of those dying, even more if the health service collapses) is your lockdown, then you will think that ending the lockdown is the height of irresponsibility. This seems to be where many people’s thinking is right now, including the government and their scientific advisers, and perhaps explains their wariness despite the monumental economic and social costs of continuing the restrictions.

This is why it is so important that people recognise that that is extremely unlikely to happen. This coronavirus did not spread exponentially to the whole population before the lockdown, it grew slowly towards a limit, and it will not do so afterwards. I’m no virologist so I can’t say why that is the case, and the virologists themselves don’t yet have a full understanding either, though they do say that coronaviruses have a typical prevalence of 5 to 20 per cent. But like most people I can read a graph, and I can see how the proportion of positive tests slows towards a low limit even before lockdown measures are imposed, and that tells me all I need to know right now. It tells me this virus does not keep on going but reaches a natural limit, and does so independent of political interventions.

I don’t know whether the lockdowns have slowed it down further, presumably they have had some effect. In a way that doesn’t really matter, at least for this outbreak. What matters is that government and the public come to see, sooner rather than later, that you don’t need a lockdown to avert a catastrophic contagion. Until we get to that point – which might only come by looking at how other places with less severe measures fare – expect restrictions in some form to stay in place.