Prologue

Each night I say the same prayer. Three prayers really. I thank my Lord for all the good things He has given me. Despite my tiredness I am the luckiest of men, with the sweetest of wives and a young son who is the true light of my life. Then I ask my Lord to keep safe my wife and my son, and to allow me life long enough for him to grow strong enough and old enough to care for himself and his mother. Finally, I ask that I be forgiven. My sin is greater than that of a killer or a thief; greater than that of an adulterer and a blasphemer. I am so ashamed of my sin and I am so covetous of it. I beg to be forgiven but I remain indignant and proud of my sinning.

Each night I say the same prayer. Three prayers really. I thank my Lord for all the good things He has given me. Despite my tiredness I am the luckiest of men, with the sweetest of wives and a young son who is the true light of my life. Then I ask my Lord to keep safe my wife and my son, and to allow me life long enough for him to grow strong enough and old enough to care for himself and his mother. Finally, I ask that I be forgiven. My sin is greater than that of a killer or a thief; greater than that of an adulterer and a blasphemer. I am so ashamed of my sin and I am so covetous of it. I beg to be forgiven but I remain indignant and proud of my sinning.

Fleeing Bethlehem

I’m old. My young wife laughs and assures with a soothing voice that I am not that old, but her eyes tell me that she knows my years are almost at an end.

I mutter now all the time. I realize no one is near enough to hear my complaints but I continue, determined to be heard, even if only by God. When I first noticed my muttering, I was embarrassed and would force myself to stop. Not anymore. I am at that cusp of awareness: aware enough to know people snicker behind my back but too indifferent to care that they do. Soon I will no longer realize I am aging or that I am muttering, but I will always know I am tired. So tired. And ashamed.

The last two years have been particularly difficult: leaving my older children behind in Nazareth, ignoring the entreaties of my brothers and cousins to stay, trying so hard to settle here in Bethlehem and eke out a living for my new wife and our newborn child–though he is not quite a newborn anymore. Almost two years old now and a bundle of energy and light. Such a delightful, cheerful, loving child. At least usually. Recently, the cries of the child have kept me up. The young boy’s nightmares worry me. He is terrified about something, but he is still too young to tell us what frightens him. So he cries. The child cries almost every night now. And there is something else keeping me awake: the muffled weeping of my wife. Those silent female tears splash loudly and lay siege to my graying brow. There is no escaping those two; mother and son are as one in their joy and their fear. Nor is there any escaping God. But we must escape this place. Now.

“Mary, it is time, wake up,” I whisper. But she barely moves and, as it is with old men I feel a sudden fear engulf me. “Mary, my sweet love, are you sick? Has something happened to you?” I am now almost frantic with fear, but then a wry smile creeps across her face and she opens her startling green eyes all at once: “I’m fine, my sweet husband,” she responds. She puts an ironic stress on the word “sweet” to provoke me, and I cannot resist responding, irritated: “I am not very sweet,” I protest.

“That’s true,” she smiles impishly, “and that is what makes these small moments even sweeter for me.”

She is always teasing, but somehow it never angers me. This would surprise my kinsmen. I have a terrible temper. I argued all the time with Ester, my first wife. Even as she lay dying the arguments did not abate; I hate myself for that. I should have been more understanding, more tolerant. But I never could control my anger in those days. I once nearly killed my eldest son, James, for talking back to me. But that was years ago now and it seems it was a different person who raised that mallet in fury when James berated me, calling me a traitor and a pig for betraying his mother’s memory by choosing to wed again. It is hard for a boy of 14 to watch his mother die, but it is far harder for that same boy at 16 to watch his father remarry. I should have used that mallet on myself. How dare I raise a hand to my beloved firstborn for defending his mother? And what a wonder and joy he has been, tending to his younger siblings after Mary and I fled Nazareth two years ago, and what a joy it will be to see him again if we ever make it back home to Galilee.

“Mary, we must leave this place.” She looks at me with a face lovelier than the stars and smiles a smile that outshines the sun. Such drivel, I know, I am no poet, I am not good with words. The townspeople look at me and laugh when they see how I dote on my wife. They think it funny–even pathetic–how this old man endlessly compliments and caters to his wife, lavishing endearments and affection on her. When I tell her how beautiful she is, how she easily rivals the sun and stars, she laughs at me and it almost–almost–makes me feel foolish to talk like some second-rate psalmist. But I never really feel foolish though my words are those of any lovesick fool, and I cannot get angry when Mary laughs at me; her laughter is too pure, too loving, too playful. “Mary, really, we must go now.” She looks at me more closely now, her smile weakens, she knows how tired I am and she knows I am truly worried.

“Are we returning to Nazareth, Joseph?” she asks.

“Not yet, Mary. Not yet. I don’t think it would be safe there either.”

“Not safe? Are we in danger here? she asks, but there is more sorrow than fear in her voice. She is sad because she knows how I yearn to return to Nazareth to see my other children again.

I mutter that we are in danger everywhere, but especially in the realm of that madman Herod. “We must go, go far away, perhaps into the Sinai and wander there for a while like our ancestors did long ago.”

“But you are so tired, my darling. And the little boy is finally settling down and enjoying life here.”

“He is not settling down!” I say a little too sharply, and immediately regret my harsh tone. More softly I continue, “You heard his screams through the night. He senses something wicked coming; he barely speaks, but I see the fear in his eyes. We must go. We cannot delay even a day.”

“What! You mean to leave today? Just pick up our things and go like criminals running from the law?”

“We are criminals, Mary!” The urgency in my voice startles her, but she needs to understand. “We are criminals,” I repeat. “Our son is a crime. Somehow, he is a threat to the King and the King is sending soldiers to do away with the boy.” She looks at me like I’m mad, but we both know the truth: it is the King who is mad; this world that is mad. “Can you imagine,” I ask, “a mighty king afraid of this little boy? What a godforsaken world we live in.” But the bitterness of my words only strengthens Mary’s confidence in God and love. “This world is far from godforsaken, Joseph,” she sternly answers and looks fondly across the room where Yesu is still deep in sleep. She smiles and there is something about her smile that is both reassuring and troubling. But I don’t ask her what is wrong. There is no time for idle chatter. We need to get out of Bethlehem quickly!

Within an hour we are on our way. The donkey is loaded with all our belongings and it is still unburdened. We have very little clothing, a single pot to cook meals, two earthenware bowls, and some bread and salted fish that we had purchased the day before. We also take a few carpenter tools; a means to ensure our livelihood and perhaps a means to defend us from bandits. We walk until the sun is high in the sky and then we stop to rest. Yesu has been on my shoulders nearly the entire time. He is a quiet child, but sometimes his words are more unnerving than his silence. “Father,” he asks, “where us go? I so tired, Father.” How can I explain how strange his words sound to me? He struggles to form full sentences, but he formally calls me “father” like a much bigger boy! Such an odd juxtaposition. I have been around children all my life; I have many other children of my own. But none ever called me father until they were much older and even then, only rarely. He seems too young for such formal words; he certainly is too young for the danger he is in.

After a brief rest we continue our exodus from Israel toward the land of the Egyptians. I laugh to myself as we trudge along as it occurs to me how my famous namesake so many centuries earlier did just the same under oddly similar circumstances: the threat of death; the jealousy of others. But this is different. The Patriarch Joseph was at the center of that story; I am barely a footnote in this one.

My mind wanders as we wander along the barren trail through the desert. How did I get here? How so late in life did I find love that only a young man is strong enough to bear? For years I tended alone to my sons and daughters as my first wife’s illness worsened. As I watched my children grow, I also watched Mary grow. As I watched Ester die, I watched Mary blossom. That guilt still haunts me. I loved Ester deeply, but ours was never a happy union, never a true bond of joy. So for years, each day as Mary walked past my small shop where we lived and where I once made wooden chests and short-legged tables, I watched her. Just seeing her soothed me; I never intended to marry her; I was content to just enjoy her presence in the village. Once, seeing her as she made her way to the market, I was so distracted I severed to the bone the fourth finger of my left hand. That finger now aches whenever it rains or a cold wind blows or I think too much of how much I love her. The pain is a constant reminder of my love and my lust and my mortality.

It has not even been two years since we fled Nazareth, and now here we are fleeing again. Yes, we fled Nazareth; we did not leave to register for the census and pay taxes; that happened years later. But it is a useful myth. So much more palatable than the hard truth: we fled Nazareth because my wife was with child and we had not been married long enough to hide from the gossips and the mathematicians. When Mary first told me about the pregnancy I was stunned: how could such a chaste, honest woman be with child? But when she explained to me her strange encounter with the angel it made perfect sense to me. I know, I know, most men would have scoffed and gotten angry–men with far better tempers than mine would have gone mad with jealousy and righteous fury, but not me. And that was, to me, more of a miracle than her being with child. How can I explain, even to myself, how easily and unequivocally I accepted her explanation? How easily and unequivocally I trust her.

In Bethlehem I thought we could start anew and live life far from the prying eyes of friends and the sweet venom of relatives who would grin and shake their heads at the foolish old man who could not count months. The mockery I could bear. For Mary I would happily bear anything. But I could not bear what they would think of her. I could not tolerate their eyes judging her–and I could never risk people calling for her to be stoned. Bethlehem seemed safer. But not anymore.

We walked on for many days, more than a full cycle of the moon, but less than the 40 days or years we Jews like to attribute to almost every journey or travail. We made our way slowly into the Egyptian desert, stopping along the way to beg food or to offer my services as a carpenter or merely as a common laborer. One day I looked up and saw in the near distance, looming high above the horizon, that sacred mountain that Moses once climbed. I stopped in reverent wonder, but Yesu tugged at my arm and pointed to the mountain peak, “There, Father, there.” I looked at him confused; he could not mean for us to climb that mountain. Admittedly, it did not seem like it would be too difficult; I could see several goat paths that appeared easily enough to follow with only a little effort. But why do so?

“Yesu, my darling boy, we must make our way to a village and find food and work.”

“Father, please, there,” pointing again to the summit of the mountain that now seemed to be bending low to lift us up.

“Yesu, I’m sorry, we just don’t…” Mary interrupted: “Husband, I know you are tired. Rest here where these palm trees give shade. I will bring our son up the mountain.”

“No Mama. Father and me go mountain. Both us.”

I stared at Yesu and wondered why I must go with him, but his mere asking was enough to restore my strength. Turning to Mary I conceded: “If he must go, then I must go with him.” And that was that. It would be dark before we descended and he would need my protection; that must be why he chose me to go rather than his mother.

When I looked down, Yesu had already taken hold of my hand. He smiled up at me and said again, “There, Father, there.”

The walk up was harder for me and easier for my son than I would have guessed. The path was sometimes hard to find and it often skirted along high precipices. I worried that the little boy would trip, but he was sure-footed and confident. By the time we reached the summit the sun was near setting. Yesu let go of my hand. He stood absolutely still and gazed all around until his eyes settled upon a spot where a large rock formation jutted out of the ground and cast an odd shadow as the sun was disappearing. The shadow vaguely reminded me of two planks of wood crossed and upright. We carpenters are so unimaginative. Yesu became silent; I was not even sure he was breathing. He just kept staring at that shadow until the darkness washed it away and then looked up at me with that loving look that always melted my heart. He took my hand again and said, “We go, Father. We go home.”

“Home?” I asked bewildered.

“Home, Father. Safe now. We go home, please.”

The climb down was not as dangerous as I feared for the moon was nearly full and it bathed the mountainside with enough light to ensure a safe descent, but it took several hours and we walked in complete silence. I was lost in my thoughts about where exactly “home” might be and hardly noticed that Yesu was gripping my hand harder than I thought possible. He started to tremble and I grabbed him up in my arms and hugged him tight. He clung to me with all his child-strength as he wept and I smothered his head with kisses. I started to weep too and did not know why. Yesu held me tighter. My tears ebbed, but my body shook with love and fear and fury. The last hour down the mountain I walked with him stuck to my chest like an infant clinging to his mother’s breast. He wept and wept. What had he experienced on the summit that scared him so?

As we completed our descent, Mary ran to us with bread and kisses to nourish our bodies and hearts. We accepted both hungrily. Yesu could hardly restrain himself when he saw his mother, “Mama, mama, my mama!” and his joy was boundless. I smiled happily on seeing her too, but she saw the sorrow in my eyes. I can never hide how I feel from her. “What is it, Joseph? The climb was too great a strain? No? Then what is troubling you?” I shook my head and said it was nothing, nothing to discuss. Mary, despite her gentle manner, could be tenacious and she sought to interrogate me further, but Yesu saved me from a dark confession. “Mama,” he interrupted, “we go home! Father says we can.” I did not, of course, say we could, but saw no reason to contradict the dear little boy. It was only much later that I realized he had been referring to his other father. That is how it would always be: the three of them bound together like three braided strands of hair: my son, his mother, and God. And me hovering near, but always apart.

Reaching Nazareth

It took us many months to wend our way slowly back to Bethlehem, but long before we got there, we heard news from passers-by that mad king Herod had died a horribly suitable death and now his sons were all too busy fighting each other to threaten the common people. We stayed in Bethlehem only a few days and then Mary agreed it was time to return to Nazareth and rejoin our kinsmen and my children. Along the way we passed a small contingent of Roman legionaries. The commander noticed my carpentry tools and asked in surprisingly fluent Aramaic if I would like some quick cash to make some items they needed. The prospect of work and enough money to feed my son and wife made me utter a thousand prayers of thanksgiving. Such good luck! Such an unexpected gift from God! I eagerly agreed and the Roman brought me to a fenced-in corral where about a dozen unfed and severely beaten men sat, bleeding and moaning.

“What is this? I asked in horror.

“This,” the Roman smirked, “is your work. These men rebelled against Kin, Archelaus; they will now get what they earned.”

“By torturing and killing them?”

“What else?” he laughed. “They will all be crucified. We will make an example of them.”

This is what had happened. At Passover that year, after Herod died, thousands of devout Jews poured into Jerusalem to pray at the temple. Fearful that the rabble might get out of hand, Archeleus sent soldiers to monitor and control the crowd, but the presence of the soldiers had the opposite effect–inciting the crowd to violence and precipitating many deaths, including a large number of Archeleus’s soldiers. Then at Pentecost, a mere 50 days later, a still larger crowd gathered at the temple, but this time the authorities were better prepared–a Roman legion had been summoned to Jerusalem. The presence of the legionaries predictably provoked the crowd and the Romans reacted firmly when the rabble rashly started throwing stones at them. On the first Pentecost God gave us the 10 Commandments; on this Pentecost the Romans gave us a different kind of lesson: more than two thousand were captured and crucified.

“You Jews will learn soon enough to bend to our will and obey our law… and respect our ally.” The Roman looked at me and must have seen the disdain in my eyes. “It is all the same to me, Carpenter. If you don’t make the crosses, someone else will. You would be wise to take the work and the money.”

“Wise? Having wisdom and being pragmatic are not always the same thing,” I answered angrily.

“And what is wisdom?” he smirked.

I looked at him in silence for a moment. What an odd question. Only a Roman would be dismissive of something as sacred as wisdom. He might as well have asked What is truth? but I was wary of mocking him and held my tongue. Instead I replied cautiously, “In our sacred scriptures it says that fear of God is the beginning of wisdom.”

The abruptness of his response was typically Roman: “What the hell does that mean? It makes no sense. What an absurd notion. Courage is what makes all other virtue possible, we Romans like to say. Fear is something to face… and kill.”

“You are speaking of a different sort of fear. Have you never feared to anger someone? Have you never feared to hurt someone you love? You, a Roman centurion, have you never feared failing in your duty? Have you never been overwhelmed with how small and unimportant you are compared to the vast world around us?”

“I am a Roman,” he answered, adding without even a hint of irony: “No Roman is unimportant.”

“So you have never looked up at the stars and felt small? You have never looked within yourself and worried you are not who or what you should be? These are all fears, like the fear of God, which bring us nearer to wisdom and humility.”

“And somehow refusing to work and make money is wisdom?”

“Perhaps fearing God means that it is unwise to always be practical and pragmatic. That doing what makes sense in this world is not always wise and is not always what God expects of us.”

“So,” the Roman laughed, “we should do whatever our priests tell us and if we starve to death or lose all we have, then that is just fine?”

“I doubt the priests have any better understanding of what God wants than you and I. But we strive to do what is good and right and… and to avoid the great temptation to always be practical.”

“Ha! What a mess this world would be!”

“Ha, what a mess this world always is!” I hesitated and then went on, “I am not saying we can ignore the world or wage war against it. I am only saying that there are limits to compromise; that there are limits to how far we should go to accommodate this world… or we risk losing who we really are.”

“And who are we?” But I detected in his tone a subtle change. He was no longer sneering; he was genuinely earnest to know what I thought. This itself was bizarre. A Roman asking the opinion of a Jew, and a mere itinerant carpenter at that! But I saw no harm in indulging him. “Who are we? That,” I smiled, “is clear: we are children of God. All of us. And while I must live in this world and sometimes do things I would rather not do, making crosses to crush the bodies of my fellow men is not one of them.” He looked at me and that now familiar sneer crept back onto his face. I could see this discussion was useless, so I started to walk away. He grabbed at me and took hold of my left hand forcefully. The old wound came alive and I pulled away sharply. The Roman was surprised to realize that he had hurt me and took my left hand in his again, but more carefully, almost gently. As he examined my hand, he started to talk with a hint of kindness in his voice: “I noticed you have a young wife and very young son.”

I felt my face burning. How dare he mention my family! Was he trying to threaten them? “Yes, what of it?” I asked defiantly and yanked to pull my hand from his grasp, but to no avail.

“I meant no disrespect, old man. It was an innocent question.”

“Was it? They have nothing to do with this. Leave them out of it.” My voice was threatening, but he didn’t react in kind.

“They have everything to do with this. Here you are ready to wage war against the legions of Rome because I merely asked you about your family and yet you give up a chance to feed your family and clothe them and make their lives easier?”

He had a point. I had risked my life and theirs with a response most Romans would deem insolent. What a fool: still unable to control my temper after all these years. But how could I explain my refusal to build those crosses to a Roman who believes pragmatism a Godly virtue? I looked toward the corralled men already beaten into submission. “My wife and child are everything to me,” I explained in almost a whisper. “And these men will die whether I hammer the crosses together or not. But to make those crosses makes me as guilty as you in killing them.”

His laugh was a roar. He let go my hand and whacked me heartily on the back: “There is no guilt. These are criminals. They deserve death.”

“Perhaps you are right about that too. But when I look at them, all I see are broken, frightened men who are as much God’s children as you and I.”

Without a hint of ridicule he answered: “You’re a fool.” And just as matter-of-factly he added: “But perhaps it is true that the gods protect fools who refuse to protect themselves–and who refuse a chance to make money. Not many Romans or Jews would give up a chance to make money. We always find excuses to do whatever we want to do.”

“Yes, we all justify things that have no justification,” I agreed, sighing.

He again took hold of my left hand and he was now carefully pressing at different places to find the injury. When he pressed on the fourth finger the sharp jolt of pain made me wince. For some reason this made him laugh again.

He must have understood the shock and confusion on my face because he quickly apologized. “I’m sorry. But I should have guessed! Of course it would be the “vena amoris” that inflicts pain on one such as you.”

“I have no idea what you are talking about, sir, it is just an old knife wound from many years ago.”

“There is a vein,” he explained, “that runs from the fourth finger of the left hand all the way to the heart. We call it the vena amoris and it is why we Romans sometimes wear rings on that finger–to show our love and devotion to someone.”

“Ah, I see. And my loves, my devotions, will always cause me pain?”

“Well,” he answered slowly, now weighing his words carefully, “perhaps it means that your feelings are so deep and so certain that you always ache with love.”

I smiled at that and he reciprocated in kind. He then grabbed hold of my right forearm as Romans do and bade me farewell, thanking me for almost restoring his faith in the goodness of men. If only he knew how far from good I really am.

Days passed and as we neared Nazareth I was overwhelmed with dread and anticipation. Nearly three years had now passed. How would James and my other children treat my new wife? How would they act toward my little Yesu? He was so sensitive and joyful–and yet had such a temper like his father! But I was foolish to be apprehensive. The countryside was calm since the Romans quelled the rebellion and so too my family had calmed down and readily accepted Mary and Yesu into the fold.

As we entered the town two of my younger daughters saw me and started screaming loudly, “Papa, Papa! Papa has returned.” Soon we were surrounded by family and friends, including my first-born and first-loved James. “Little brother,” James smiled, patting Yesu on the top of his head gently, “I have been waiting so long to meet you.” Yesu smiled up at James and pulled him down to his level. He stared at James intently for just a moment and then kissed him with an exuberance that caused James to lose his balance and fall to the ground. Everyone laughed and my other children joined in, surrounding Yesu and taking turns hugging and kissing him. Mary caught my eye and smiled. Does heaven really hold a greater joy than having the woman you love smile at you?

The homecoming celebration lasted deep into the night, but I had gone to sleep much earlier, my aging bones unable to keep pace with the festivities. By the time Mary joins me it is almost dawn. She slips under the wool blanket and places her left arm across my chest and squeezes me tight enough to awaken me. “Keep that up, Mary, and you will kill your old husband. I can hardly breathe!” In response she squeezes me even harder and laughs quietly, whispering that I am not as frail as I pretend to be. She then entwines her left leg over my left hip to ensure I cannot escape and we both fall into a deep slumber.

Seeking Yesu

The years passed too quickly, as they always do when you are old and happy. I had now lived far longer than I had ever expected. “Perhaps you would prefer to be young again? Young and unhappy and confused, and experience life as a never-ending series of mishaps and disappointments?” Mary teased one day. “Then the days would truly slow down,” she laughed, her eyes widening in mock horror. She was right, of course, to mock my lamentations. I have a good life, but the days do tumble by at a dizzying rate and my Yesu is now nearing his 12th year.

And our world too is changing. Less than a decade ago the Romans were steadfast defenders of Archeleus, our “legitimate king,” and now they have deposed him. Archeleus, once worth crucifying 2000 of the rabble, is now just rubble to be tossed away. These Romans! No longer just our protectors; now they rule us with little pretense or regard for our sovereignty. They now protect us from ourselves. Archeleus’s soldiers have been commandeered and are now commanded by the Romans. Yet, we are a burden to Rome, and they expect payment for their services. Subjugating us has been costly and molding us into a proper Roman client state will be even more costly, so they had ordered a census so they could tax us more efficiently.

But I have other matters to tend to. We are traveling to Jerusalem to present Yesu at the Temple. We are proud of our son; he has grown into a fine young man. He is loving and attentive to both his parents. His affection for us is boundless and his devotion to his mother rivals his love of sacred scripture.

Getting to Jerusalem should only take three days, but I am well past 70 years. By the second day my whole body is aching. I find it harder and harder to breathe and my left arm frequently tingles and then numbs. But still we move on. On the evening of the third day Mary notices me rubbing my left arm and takes hold of my left hand with both of hers. I wince, but smile at her. She urges me to rest. “Come, husband, lie down for a while and rest. It has been a long day of travel.”

“No, Mary, first I must unpack the donkey and prepare a fire for our evening meal.”

“Nonsense, Joseph. Yesu will tend to the unpacking and he can also help me prepare the meal. You need to rest.” She sees the reluctance in my eyes and adds with a grin that is both charming and threatening: “Now!”

“As you wish. For a few minutes only.”

“Fine. Just lie down for a few minutes,” she repeats, rolling her eyes like a spoiled, petulant child of a tax collector.

Many hours later I groggily awoke as Mary quietly joins me under the covers. Instinctively, she reaches for my hand, entwining her fingers with mine, gently kissing each of my fingers in turn and then presses my hand tenderly against her chest as I fall back into a deep, dreamless sleep.

The next morning was bright, and the sun shimmering on the desert sand offered us the illusion of a pool of cool, refreshing water in the near distance, just out of reach. Those desert mirages are a constant reminder to me of how life often is: what we want most always just out of reach, no matter how far we travel, no matter how hard we work, no matter how much we pray. My secret sin intrudes again, searing my thoughts and muddling my mind. It becomes one with the mirage. I am left parched and lost in my foolish yearnings.

In the early afternoon of the fourth day, the landscape starts to change, with more cultivated fields and seemingly endless palm groves. I look up and I see the city of God now shining above us. Jerusalem! My heart aches with joy at seeing again the sacred city. So many years since I was last here; I am grateful to God for the chance for one last visit.

A pilgrimage to Jerusalem is always a joy for any traveler, even those lacking in faith and devotion find delight in its beauty and majesty–or at least its earthy pleasures. There is a constant throb of music and merchants, and the exotic smell of spices overwhelms the senses, even as the pungent odor of dung and filth vie for attention. Jerusalem is full of holiness and sin, but it is still Jerusalem, our sacred city. And for us this visit is particularly joyous because our son will stand before the priests and he will read from sacred text to the assembled crowd.

The sun fiercely bore down on us and made the winding path leading up to the walled city glisten like a silvery snake. Excited and euphoric, I pick up the pace and Mary and Yesu struggle to keep up. They laugh at the speed of my ascent up the rocky path and call for me to slow down. I look back in the shimmering sunshine and in surprise find them thirty silvery paces behind me. They see the look of surprise on my face and their laughter increases. There laughter is so loud it seems to fill the vast emptiness of the desert. And it fills the vast expanse of my heart to the brim with joy and love for these two gifts from God. How can I be so grateful and so unsatisfied at the same time? I shake my head at my own pettiness and mad desires.

Mary seems worried. When she finally catches up with me, she caresses my cheek with the palm of her hand, she kisses my other cheek gently, and then sternly admonishes me: “Slow down, Joseph! You are not young anymore!” Yesu enters the fray: “But Mama, I doubt if Father was ever young.” I reach out a hand to smack him, but he easily evades my feigned fury and then grabs my hand and holds it tight. “Mama is right. You must not exhaust yourself, Father. We will get to Jerusalem long before sundown without hurrying.” His smile both soothes and aches my weary soul. Not letting go of my hand, Yesu and I walk together more slowly toward the walled city’s narrow gate.

The next day in Jerusalem matched the last: a cool, bright morning married to a warm, even brighter noon. We walked slowly toward the Temple while the air was still cool, but as we neared it Yesu changed. Only someone who knew him well would notice the change: he was walking more upright, with more confidence, but also there was a certain tension in the muscles of his jaw. I didn’t know why and when I turned to Mary she shrugged her shoulders: she too had noticed the change but could not discern why. As we approached the first steps, Yesu stopped, a brief glimmer of anger in his eyes. He turned to me: “Father, what is this?” Confused, I hesitated; he of course knew this was the temple. Before I could state the obvious, he added: “These tents? All these merchants? What are they doing so near the Lord’s house?” I knew the correct answer: “Yesu, they serve a practical purpose. No pagan coins, especially ones with human images, should enter holy ground. Those coins are exchanged for other currency, while these other merchants over here are selling animals for making the ritual sacrifice. It would be onerous for each pilgrim to bring along his own animal to sacrifice”

“Too often men argue that being practical gives them license to offend God’s Will.”

Had I not used that very argument once long ago with a Roman centurion, I thought to myself. But I answered instead: “But, Yesu, the people need to make their sacrifices and this makes it so much easier for them.”

“I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings,” he answered softly, quoting the prophet Hosea. “Merchants should not make profit off the needs and prayers of the poor. Will they never tire of taking advantage of the humble and weak?”

Mary interjected that it was time to enter the temple and present Yesu to the priests. Our festive mood had been ruined by Yesu’s anger, but he sensed our unease and warmly embraced us both, placing his arms over our shoulders. “Come, Mama, come Father, let us rejoice in this day and this chance to enter our Father’s house,” he smiled. All anger seemed to have vanished and he was again the same little, adorable boy we had been raising for the last 12 years.

When he read from scripture he spoke with such confidence and such passion that many of the priests paid close attention, although others continued napping. After he finished, one priest, named Nicodemus, approached him in private conversation. After a few minutes two others joined them. What, I wondered, could he be saying that could possibly interest these learned men? For a brief moment I worried he would raise his concern about the moneylenders and merchants, but the smiles on the priestly faces assuaged that fear. They all seemed delighted, mesmerized, with my son’s words and his smile.

Mary saw that I was weary and approached the small group of men. She pulled Yesu aside, informing him that we would go rest and that he should join us with the other pilgrims before noon. The return trip to Nazareth could not be delayed. We found my younger brother Jacob ascending the temple steps as we left and asked him to keep an eye on Yesu. He assured us he would bring our son back safely to the caravan.

But that is not what happened. Mary had awakened me from my nap just as the caravan was starting to slowly move across the countryside. Still groggy I helped Mary gather our few items, packed everything onto the donkey, and off we went. It was not until much later that I asked about Yesu. Mary laughed at my worry and assured me Yesu was with his cousins and Uncle Jacob. But when another three hours passed, I went to find my brother who said he had not seen Yesu since the Temple. “But where is he? We left him at the Temple with you. With you! Jacob, where is he?” My hands, seemingly with a will of their own, had grabbed Jacob’s tunic and I was shaking him violently. He angrily knocked away my hands and pushed me away. I started to fall, and blindly lurched to grab hold of him again. Jacob moved quickly and I stumbled downward, scraping my knees on the rocky ground.

Ashamed and angry, Jacob tried to explain, “I tried to get him to leave with me, but he was deep in discussion with the priests. He told me he could find his own way back to the caravan. He is 12 years old, Joseph. He could easily find his way back alone from the Temple.”

“Apparently not!” Frightened and exasperated I couldn’t stop myself, “Damn you, damn you, Jacob!”

“This is not my fault,” he growled through his teeth.

“No, Jacob, it is my fault… for relying on you.” I brushed off the gravel stuck to my bleeding knees and rushed off.

“Where is my son?” I screamed to no one, and it was more a plea than a question. “Where is he?” I repeated again to God and now it was more an accusation than a prayer. My voice was loud and the empty desert carried it far along the caravan. My body started to tremble and a dark dread grabbed at my throat. Jacob was running after me, apologizing and blathering some nonsense about Yesu now being a man, but I could not hear him clearly as my mind reeled with phantom fears. He took hold of my shoulder and I turned toward him with fists clenched, but Mary grabbed my arm as I raised it to strike Jacob. “Husband, please. Stop. We must focus on finding Yesu. We must head back to Jerusalem quickly.” Her voice was enough, as always, to calm me. She apologized to Jacob with her eyes and hurriedly led me away.

The moon had not yet risen when we reached the city, and it was shrouded in a stark blackness that suited my mood. As we approached the Temple we saw torches lit inside and vaguely saw the same small group of priests huddled around in a tight circle. I prayed Yesu was still among them, but I doubted it. I could not dawdle any longer. I ran as fast as I could, racing up the temple steps before Mary could stop me; my legs started to wobble and my heart pounded erratically. My lungs felt like they would burst but I needed to find my boy. I knew he would be long gone from the Temple and these damn fool priests would not even recall him being there, but still I raced forward.

Yet there he was. Still sitting among the priests, speaking reverently, calmly, with a confidence and authority that would have angered the high priest, Annas. But Annas was not one of those surrounding my son and it was my anger, not that of that fool Annas, that they would need to contend with. “Yeshu’a!” I screamed and I heard a fury in my voice that I had thought no longer possible. “Where have you been? How could you just leave us?” The priests were stunned and all looked at me as if I were a madman. Indeed, I was. I had lost all control and I approached the small group like an animal ready to render them a bloody mass of flesh and broken bone.

Yesu was at my side. I don’t know how he moved so quickly, but he already had hold of my left hand, gently pressing it. I reflexively winced, but I felt little pain for the first time since the injury 15 years ago. “My Father, I am sorry. I should have realized you would be worried. Please forgive me.” My anger melted and I found myself asking him to forgive my outburst. He just smiled and hugged me and said there was nothing to forgive. Then he whispered in my ear: “Really, father, don’t be ashamed. I have grown used to having two mothers fret over me.” His laughter was contagious and I found myself laughing as I gently boxed his ears for his effrontery. Nicodemus had gotten up and walked over to us, apologizing for detaining Yesu and explaining what a gifted, extraordinary young man he was. There is no other way to describe it than to say Nicodemus was smitten, enthralled, even entranced by my son. I thanked him, but curtly added that we needed to get back to the caravan quickly or we would have to make the entire trip back to Nazareth alone.

Mary was waiting outside the temple for us and shook her head in exasperation at Yesu: “Why have you done this? Your father and I have been searching for you in great anxiety.” But Yesu could see that her anxiety was all for me and not for him at all. She was worried that I could not endure the strain. “Mama,” he gently answered, “I must attend to my father’s affairs. You must understand this.” She smiled and nodded her head, but was that not sorrow I saw in her eyes? Why would attending to God’s affairs trouble her so? Is she just sad like any mother would be seeing her son grow up and grow away? That would be so unlike Mary.

Nazareth Again

The journey home was uneventful, but each day proved harder for me to endure. By the time we reached Nazareth I could barely move. Mary and Yesu placed me in the back room on a bed that I had fashioned long ago with little 6-year old Yesu assisting me. The bed was not so well made, but the memory still burned bright and made the bed more comfortable than it really was. A month passed and I got no better; I knew I was nearing death. Mary was worried and kept pampering me in ways that I would not allow if I had had any strength to stop her.

“My sweet darling, what more can I do to comfort you?” she asked. But the only comfort I needed was to come to terms with God, yet even in my weakness and pain I stubbornly kept hold of my grudge and anger. I felt lost and Mary sensed it.

“Joseph, what is it? What troubles you so?”

“Nothing. Nothing that I can speak of.” And I turned so my back was to her. She touched my shoulder gently and turned me back to face her. “Dearest love, please tell me. Perhaps I can help.”

“Mary, I am too ashamed.”

“Too ashamed to tell me? Nonsense, you know I love you beyond all reckoning. You stood beside me when Nazareth turned against me; you have sheltered and protected me and our son at great cost. I love you, my husband. Please tell me.”

“I… I am so lost, Mary. So confused. So angry. I trust in God, I am his servant, but….”

“But what, husband?”

I could feel the anger swelling in my chest, boiling my blood. My face flushed with fury: “But I resent Him! I am jealous of Him! My voice was a seething growl of pain and guilt: “I want what only He can have! Damn it. Damn me!”

Mary did not react in horror. She was not repelled at all by my outburst. She took hold of my hands, as she often did, and kissed them each in turn. “My husband, my Joseph, I’m so sorry. You must realize that I am your devoted—and obedient—wife. I would do whatever you wish. We spoke about that many times when we first married and you adamantly refused. It was you, not me, Joseph. I would have celebrated and relished having more children. Children that we would make together. That would have been a great joy to me. I never refused you this. Please do not be angry with God. You need only have taken what was yours to take. You know I would have freely given whatever you asked.”

I was now even more ashamed. I began to stutter and speak in half sentences. “Mary, I…. Mary, I’m so sorry. Mary, I chose… Mary, you misunderstand me. You, you are so incredibly sweet, my wife.

“I misunderstand?” she interrupted.

“Yes, Mary, you misunderstand. As you say, we spoke many times long ago about this. I know you would never deny me anything, nor has God. Before our marriage I dreamt of having many children with you, but once you conceived Yeshu’a something changed inside me. I tried to explain this to you years ago, but I don’t think there are words to satisfy either of us. I am overwhelmed by your beauty, but that urge you speak about is gone forever. It was for me like the forbidden fruit in the Garden. I cannot explain it, but it is gone and has been since Yesu’s birth.”

“Truly? All these years I have felt a little confused, a little guilty.”

“No, Mary, not your fault; not God’s fault even. Perhaps I just am too old.”

“Ha! And all this time I thought I made you feel young again!” she teased.

Her smile was so radiant I could have kissed her if I could have lifted my head. She must have understood my desire and bent down and smothered my face in kisses. We both smiled and our eyes, as so often, found some deep place in each other that no one else ever entered.

“You don’t make me feel young, Mary. And I never forget that I am old.”

“Well, that is a little disappointing,” she laughed. “Must you always be so blunt?”

“Let me be blunter: You don’t make me young; but you do make me happy. And that is a far greater miracle.”

She smiled again and then turned sad: “I am yours entirely. God brought us together. He is the real reason for your happiness. How can you resent Him? How can you be angry with Him?” She was not going to leave me alone. Even on my death bed she would be unrelenting. Most people who know Mary are so ensnared by her kindness that this less pleasant aspect of her personality remains hidden. She brings joy to all those who know her, but this serves to hide what an obstinate donkey she can sometimes be! Meek and mild maybe, but also a cantankerous camel when her mind is made up!

“Joseph, please, you must…” There was a hard pounding of footsteps outside the house and then the slamming of the door. It was Yesu, arriving out of breath and full of fear. He had gone to the market for some items his mother had asked for my broth: garlic, onions, rosemary branches and some other herbs. He almost always went willingly, but today he had delayed so long it was almost dark before he left the house for the market. He was uneasy when he left; he was now frantic as he returned.

“Father, father,” he almost screamed, between gasps of air. Frantic, confused, he seemed so much the little boy I carried down Sinai so long ago: “I’m sorry I took so long to get home. The market was closing up and it took time to find the things Mama needed. How are you, father?” And I could see the worry in his eyes.

“I am fine, my son. I am just old and in need of rest.”

“Your father is getting worse — and he has not made peace with God,” Mary interjected. The words were uncharacteristically blunt, but the voice was soft and loving, as always. Yesu looked confused, and turned first to Mary then to me and then back again to Mary.

“I don’t understand, my father is the best of men, the kindest and the most loving. How could he not be at peace with God?” Yesu then turned to me again and just stared silently. For all his keen intuition and sensitivity to others, he could not comprehend my great sin. His love for me blinded him to the depths of my madness.”

“Yesu, do not trouble yourself about this. I need you now to care for your mother since I can no longer do so.”

“No, Father, it is not time to leave us.”

“It is, my boy. It is.” And tears welled in my eyes as I saw the tears cascade down his cheeks.

“Why are you angry with God?” That certainty that arrives with adolescence was nowhere to be seen now and that aura of infallibility that Yesu had been cultivating since he was a toddler washed away with his tears. He was in pain and his confusion about his father served only to sharpen his pain. I needed to try to console him.

“I am not exactly angry with God, Yesu. I, I envy Him.” I must have sounded insane, for the look on Yesu’s face was one of complete confusion.

“I do not understand.” Looking toward Mary he added: “Mama, what is father talking about?”

“There, you see? Again, again, always the same!” and the indignation in my voice seemed like it was not mine; could not possibly be mine. “She is your Mama, the center of your life. But that is not my place. No, that place is only shared with your mother and God … and I am reminded of that every day. I know, I know, being jealous of God is madness, but I begrudge him his relationship with you, with my son, my son. You are mine!” My body, racked with pain, still ached for that love I could never have. The three of them were the real family. I was just a necessary — pragmatic, as the Romans would put it –- appendage. I knew I was being selfish, and in my pain I struggled to control myself. “You are a good son, the best of sons, but I know I am not within the nearest circle of your heart. Mary is your Mama; I am merely your father,” and the look on his face surprised me. “It is true,” I argued defensively, “don’t try to deny it. You always call me Father and your Mother you always call Mama. It is a small thing, a silly little thing, but it has great meaning.”

Yesu’s face changed from one of deep sorrow to almost merriment. The smile on his face was so radiant I felt at once irritated and at ease. “Oh Papa, you foolish old man. Does a name really mean that much to you that you would harbor resentment of God? Father is merely a sign of respect. A sign of my obedience and a proof of my devotion to you,” he soothed. “That is the reason I call you father. The formality is not meant to create distance. There is no distance between our hearts.”

I shook my head weakly. “Yesu, it is not just the name. I am not that foolish and petty. But the name is an indication of a deeper truth that I must accept. That truth is that I don’t fit. There is no room for me in this family. I’m just a surrogate for your real father. It is the three of you who move this story along. My part could be discarded and all would be as it is anyway. No one will remember me and I don’t care at all. I don’t need to be remembered; I don’t care to be honored. I don’t give a damn about any of that. But you. You are my boy, my son, my one true joy. And yet you aren’t. Another stands ahead of me in line, hovers above me, and embraces you with His infinite Love.”

Yesu just looked at me and stroked my brow with his hand: “I love you so much! How could you think ever that you were not at the very center of my life? You taught me the greatest of truths before I even learned to speak. When the villagers turned their backs on my mother, you stood beside her. When they mocked you as a gullible old man, you did not waver. When they laughed at you, you ignored them and prayed for them. Such a humiliation; even your own children berated you and insulted you. No one would have condemned you if you had refused to marry my mother; no one would have judged you cruel if you had rejected us. But you didn’t. Has there ever been a greater expression of love and trust in the entire history of the world? Father, you showed me that mercy always triumphs over justice and law. Papa, you chose to offer love and mercy rather than choosing to be the victim of a cosmic joke.”

“Yet, Yesu, you are not of my blood. That makes some difference.”

“It makes no difference,” and I could barely detect in his voice that deep, frightening anger that rarely shows itself in him. “As a little boy I knew so much and understood so little. You guided me every step of my journey until now,” and that same wise old child-smile filled the room.

He was crying again. So was I. “No, Father, I am not of your blood, but it never mattered. I am of your heart; you are of mine.” I felt like a foolish old man who had nursed a meaningless grudge for all the years. But perhaps that is the way it is with many men. We construct fictions, petty hatreds, and even pettier desires that take control of our lives and enslave us. So it has been since the Fall: a collective madness that isolates us from love and fellowship. The room was darkening although it was only midday. My eyesight was fading and my breath was fitful and shallow. I could feel Yesu place his arms around my worn body; his arms so strong and young and full of love. A tear fell onto my face and I smiled and sought to soothe my darling son but no words came. He grabbed my hands tightly. The old pain in the left hand was gone now; his fingers entwined with mine and the last thing I recall is feeling his body shake with grief.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

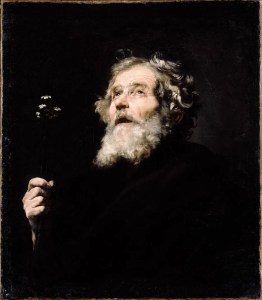

The featured image is “Saint Joseph” (1635), by Jusepe de Ribera:and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.