Which print journals are still worth reading? Herein you will find my favorite ones, in alphabetical order.

The scholar and researcher Stanley Kurtz once opined that one can really be a great reader in only one of three categories: books; journals and newspapers; or the internet. I’m not sure if it’s true, though it probably is. It may well be that Mr. Kurtz’s notion of being a great reader is itself dependent on another distinction said to originate with the ancient Greek poet Archilochus and riffed on by the twentieth-century philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin in a famous essay.

The scholar and researcher Stanley Kurtz once opined that one can really be a great reader in only one of three categories: books; journals and newspapers; or the internet. I’m not sure if it’s true, though it probably is. It may well be that Mr. Kurtz’s notion of being a great reader is itself dependent on another distinction said to originate with the ancient Greek poet Archilochus and riffed on by the twentieth-century philosopher Sir Isaiah Berlin in a famous essay.

Archilochus said, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Sir Isaiah’s essay, The Hedgehog and the Fox, lined up famous thinkers according to whether they developed one big idea or whether they thought understanding the world was simply too complicated to be gotten without sampling from many ideas and experiences. On the hedgehog side, Sir Isaiah placed Plato, Pascal, and Proust, among others. The fox side included Aristotle, Erasmus, and Goethe. I said he was riffing because Sir Isaiah later told people that the essay was an intellectual game that people took a bit too seriously.

However seriously the essay was intended, the fox/hedgehog distinction does seem to capture a real division among thinkers—and by extension to the way that may people think about how and what to read. While I don’t know exactly what Mr. Kurtz had in mind by his comment, my contention is that hedgehoggish people are more likely to think that one category of reading (among Kurtz’s options: books, journals/newspapers, internet) promotes deep understanding and thus allows one to get at reality better than the others. They treat these categories not as genres but more as windows into certain conversations.

One meets such people all the time. They often have some theory about why one must be a great reader in their category to be a true intellectual. The modernists, with whom I have some real sympathy, will tell you how the internet has now supplanted all other forms of intellectual product because one can find the most up-to-date information possible from the hive mind and the stores of data and wisdom available—or something like this. The traditionalists, with whom I also have a fair bit of sympathy, think that only by the reading of books can one attain true understanding because books confront one with larger narratives and arguments that must be dealt with. They will scoff at the internet and even the journals and papers, quoting Charles Peguy’s line that “Homer is new this morning, and perhaps nothing is as old as today’s newspaper.”

As I am a fox, I have always responded to friends in either modernist or traditionalist camps on this issue with a certain amount of “Yes, yes…up to a point.” Reading books is indeed essential to developing the capacity for deep thought, seeing through shallow thinking, and sheer immersive enjoyment. Yet I find that both thoughtful long-form essays that have been edited in journals or newspapers, as well as the hive mind of the internet and its vast treasures, are both categories one needs to know if one is to become a successful thinker and understand certain aspects of life.

Some serious books aren’t worth the time reading. So, too, a tweet is quite often worth a thousand pages of Kant. And a good essay is, in my view and in a blatant rip-off of John Keats, a joy forever.

Perhaps it is simply a generational matter: as a Gen-Xer, I am still somewhat stuck in that twentieth century, which, following on the nineteenth, conceives of a journal or magazine as the perfect vehicle for intellectual life. I still have Irving Kristol’s lines running through my head: “If you have a good idea, start a magazine.” All generational determinism aside, I do think that print journals provide the kind of extended reflection that keeps one’s ability to think in longer forms alive while still paying attention to the world of the internet and to books, the making of which, Qoheleth tells us, will never end.

Though I may be, as my children say, “addicted to Twitter,” bundled and stapled paper journals still arrive at my house, and I still find it relaxing to dive into them. They often point me to Kurtz’s other categories—corners of the internet I would not find otherwise, as well as older volumes I might never discover. Finally, they serve the extra purposes of being a drink coaster when I cannot find one and something to swat flies and bugs when the swatter is not nearby.

Which ones are worth it? Herein you will find my favorite print journals in alphabetical order.

Claremont Review of Books. Usually with about four to eight essays and another fifteen to twenty book reviews of various lengths, this approximately one-hundred-page quarterly is filled with a great deal of political philosophy, political analysis, and cultural evaluation. Most (but not all) of the writers have some sympathy for the Claremont school of thought; all are thoughtful writers interested in keeping alive and renovating the American experiment. My favorite regular features are editor Charles Kesler’s brief introductory essay on our political state of the union; Christopher Caldwell’s rich journalistic coverage of different countries and world figures; and William Voegeli’s fact-and-statistics-rich analyses of domestic politics.

European Conservative. Edited by A. M. Fantini, this journal serves as a venue for a variety of different types of conservative thought in the modern world. In addition to new essays covering contemporary political developments, it is truly conservative in content, running essays about classic literature and art and often reprinting essays or interviews with greats such as Roger Scruton or Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn. It also is a beautiful journal, filled with art and photographs of great art. Beautiful on the coffee table, it is fun to read for its quirkiness.

First Things. The first thick intellectual journal to capture me, this monthly’s future was uncertain for a few years after Fr. Richard John Neuhaus, its founder, died. Its current editor, R. R. Reno, seems to have now gotten the journal to a very good mix of theology, public affairs, and culture. While often seen as a Catholic journal, it is ecumenical and provides rich and interesting content from serious Protestant regulars such as Carl Trueman and Orthodox such as Paul Kingsnorth. Poetry editor Micah Mattix continues to publish remarkable poetry, often on religious themes.

The Lamp. Like The European Conservative, this is a fairly new quarterly (five years old) edited by Matthew Walther. Distinctively Catholic, it publishes important non-Catholic authors such as Peter Hitchens and Joseph Epstein and provides an eclectic mix of essays from a variety of different viewpoints befitting its subtitle: A Catholic Journal of Literature, Science, the Fine Arts, etc. Foreswearing the usual same-old, same-old articles on the Catholic Literary Revival, it is interested in articles on Catholic novels and any kind of interesting literature, as well as ordinary activities. It includes regular features of Catholic convert accounts, investigations into the fascinating parts of local ecclesiastical history, and light essays. The editor often has an essay of substance, such as his recent evaluation of what the American Catholic parish should be. The winner of an annual Christmas ghost story contest is published—and it is usually pretty good.

The New Criterion. Founded by Hilton Kramer, this monthly has long been edited by Roger Kimball. Many issues have sections dedicated to the arts, poetry, fiction, or various fine arts. Each issue begins with Kimball’s own sparkling introduction, taking in the politico-cultural scene, introducing any special sections, and occasionally saying good-bye to departed friends of the journal. Regular features include columns on happenings in the theater and music worlds, as well as James Bowman’s always amusing dissection of the increasingly insane journalistic landscape. The longer pieces by writers such as Victor Davis Hanson, Daniel J. Mahoney, Heather MacDonald, and others are the epitome of serious intellectual writing without pedantry. Poetry editor Adam Kirsch’s curation of new poems and translations of old is consistently high in quality.

The Spectator World. One thing I did not know about this British magazine until recently is that The Spectator is the oldest surviving magazine in the world—having been first published 1828. Its history includes many greats such as Evelyn Waugh, John Betjeman, and Kingsley Amis, as well as many political figures (think Boris Johnson) who have used editorship of it as a stepstool to Conservative Party leadership. I started subscribing to it about five or six years ago because I kept seeing amusing and informative articles on the internet and noticed they were running a deal on the World edition of the classic. Unlike many column-heavy magazines, I find The Spectator has assembled a very good selection of writers from the mother country as well as here in the States. Roger Kimball and Daniel McCarthy write fascinating political columns. The “Life” section includes great columns by Billy McMorris (“Dad Life”), Bill Kaufmann (“American Life”), and Chilton Williamson (“Prejudices”). Regular writers include D. J. Taylor on English literature, Damian Thompson on religion and music, and Lionel Shriver on whatever she feels like writing about. A great blend of serious articles and light amusement, it’s the only glossy magazine on this list of favorites.

Do you still partake in this category of reading? If so, what do you like to find in your mailbox? Though I try not to flood our house with print, I’m always a sucker for a good publication.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

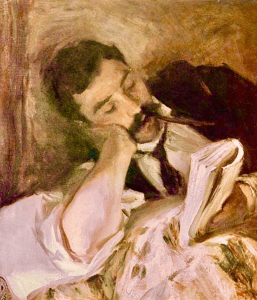

The featured image is “Man Reading” by John Singer Sargent, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.