Tomasi di Lampedusa’s “The Leopard” provides invaluable insight into 19th-century Italian history while creating a compelling story, allowing readers to relive an unfamiliar age of revolution and a fading nobility.

Time under quarantine has been an excuse to revisit a personal favorite book and to explore its history, controversy, and literary value. I can think of few books that would be as fitting for TIC’s readership as Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard. The book is a treasure, so much so, that I want to dedicate this essay to introduce readers to the story and reintroduce it to readers who have already read it by discussing its most compelling themes and lingering questions about time, modernity, and history.

Time under quarantine has been an excuse to revisit a personal favorite book and to explore its history, controversy, and literary value. I can think of few books that would be as fitting for TIC’s readership as Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard. The book is a treasure, so much so, that I want to dedicate this essay to introduce readers to the story and reintroduce it to readers who have already read it by discussing its most compelling themes and lingering questions about time, modernity, and history.

I. The Pre-Modern, Modern Man

Published in 1958, The Leopard is up there with some of the best early modern books, such as Henry Adams’ Mont Saint Michel and Chartres and The Education of Henry Adams, that describe in a very tangible, historical manner the uneasy internal shift of the 20th-century man who was forced out of an old world and into a new one. Tomasi di Lampedusa understood the spiritual, social, and political effects of this change on the old-fashioned Western man, perhaps even more than Henry Adams. While Adams was an American patrician, Tomasi di Lampedusa was an actual prince. In fact, he was the last prince of his native Sicily. The title of his novel in the original Italian, Il Gatopardo, is named after the family crest, the serval (“the leopard” was an intentional mistranslation).

Comparing Henry Adams’s treatment of modernity with Tomasi di Lampedusa’s is a helpful way to distinguish how different cultures felt this change. Adams was an American who spent many years in Europe and loved Western Civilization. His historical tales focus primarily on his exploration of these physical ruins of a bygone age, such as cathedrals, religious icons, and monasteries. Tomasi di Lampedusa was no tourist, however: He was born and bred surrounded by the types of art that inspired Adams, but instead of inspiring him, the great works of European art and mythology that he had in his own home for his leisure only reassured him that material vestiges hardly matter when the idea behind them is rejected. For what had been lost in European society after the 20th century, Adams felt sympathy; by living through the change, Tomasi di Lampedusa felt benumbed.

His novel, instead, focuses on his family’s experience of social and political change while living inside their palace, willingly confined within the old world and struggling to identify how to proceed within the new. As the main character in the novel, “the leopard” himself, Don Fabrizio Corbera, says, “Kings who personify an idea should not, cannot, fall below a certain level for generations; if they do… the idea suffers too.” The idea suffered indeed, and there was an intellectual shift that caused a distortion in our understanding of progress, which I would describe in the following way:

Cambiare tutto perché niente cambi.

To change everything because nothing changes. Tomasi di Lampedusa lived during a time when everything was being changed (by Italian revolutionaries) because nothing was changing socially, politically, and intellectually (according to the revolutionaries’ criteria). The absurdity of the revolutionary mindset, then, is precisely this desire to change radically what is not changing, never pausing to ponder if it is necessary or salutary. The novel itself is a conversation about the nature of change, but we can glean from Tomasi di Lampedusa’s writings that he believed that there is such a thing as good change and bad change; that there is necessary and unnecessary change; and, most peculiarly, that sometimes necessary change can be bad (for some). Our inability to come to terms with the nature of change is the unsettling problem in The Leopard: Was Don Fabrizio’s fate truly a natural course of history and progress? Nevertheless, the desire for vast and rapid change was the world mindset into which the great-grandson of the fictional Don Fabrizio was born, for he was not all that fictional: Tomasi di Lampedusa modelled the character after his great-grandfather, Don Giulio Fabrizio Tomasi, the first prince of Lampedusa. Lampedusa was a part of Sicily that belonged to the Tomasi family before they sold it to the kingdom of Naples in the 1840s.

This meaningful biographical information placed Tomasi di Lampedusa in a unique position and granted him a perspective that not anyone can access. He was one of the last aristocrats who experienced the push of the modern world while culturally remaining a part of the old. He had no choice, after all; his title, lacking any political role, carried with it an internal burden: meaningless importance.

How might it have felt to know that he lived among ruins in a changing world, and that these ruins were his family, home, faith, and way of life? There is nothing that he could do but watch these ruins deteriorate. He could wait for nature to run its course and slowly remove what had become obsolete, or he could bury it right away, preventing a prolonged decay through amputation.

I believe he took a middle route by letting nature run its course long enough to understand what was happening and he finally finished the job by writing his novel, burying himself in a sense. The Leopard was the only book he wrote in his lifetime, and it was rejected by two prominent Italian publishers when he first submitted it for publication. The book was not published until after his death, but it quickly became a best-seller and continues to be praised as one of the greatest historical novels ever written.

II. The Leopard’s Historical Message

I’m told that the book remains mandatory reading in various classic literature classes in Italy; hopefully it will continue to be taught. Tomasi di Lampedusa writes with elegant prose—the product of being a learned and well-read aristocrat—and a frank emotion that is anything but nostalgic. Beyond its literary value, the book provides invaluable insight into 19th-century Italian history while creating a compelling story and allowing us to relive an unfamiliar age, even Henry Adams couldn’t achieve this same form of prose in his historical books.

The plot unravels in Sicily during the period of Risorgimento (resurgence), which resulted in Italian unification in 1861. The first pages open soon after King Ferdinand II’s death, when the Bourbon State (Naples and Sicily) was ending. More specifically, the story takes place during the same time that Giuseppe Garibaldi was sweeping through the country with his voluntary army called “the Thousand.” Garibaldi is considered a “father” of modern Italy for his revolutionary efforts (his efforts awarded him good company, earning praise from comrades Che Guevara and Friedrich Engels).

Tomasi di Lampedusa lets us know from the outset that we are partaking in a momentous period in history. He dates the first chapter “May, 1860.” This was also the year that Garibaldi and his men arrived in Sicily with the intention of starting a revolution in the Bourbon State. Sicily was a strategic location, and conquering it would be a decisive moment for the Risorgimento: The unification movement originated in the north, if it could gain traction in the south, so Garibaldi thought, then it would surely be easy to take the movement all the way to Rome. Combined, King Ferdinand’s death and Garibaldi’s success were significant: It was the first time since the Roman Empire that Italy became a unified state.

The achievement of a “unified” Italy might sound like a triumphant achievement, but it was triumphant in a similar way that the French Revolution was triumphant in bringing France together. Italy certainly had less bloodshed in its civil war and revolution, and it was perhaps more democratic since it gathered support throughout the country, but Italy’s unification also came with the end of Italy’s nobility. This might not sound like much of a tradeoff, not yet, until we consider two questions about revolutionary history that we do not ask enough (or at all): Was the revolt against nobility only a revolt against a ruling social class? Or were they the momentary victims of the time, representing something deeper that ignites our human desire towards rebellion? The second question stems logically from the first: What is this “something” that human nature seeks to achieve through revolution? And is our modern, liberal world immune to these, our defiant caprices?

III. The Perennial Fight for Power

The novel’s protagonist, Don Fabrizio Corbera, Prince of Salina, is the embodiment of the response to both questions. After all, he is also the main target of criticism within the novel. A review of Tomasi di Lampedusa’s book in The Guardian compares the Prince of Salina with Machiavelli’s prince. The author of the article writes,

The art of politics is an Italian invention – politics as a self-conscious way of acting and thinking. A modern awareness that human affairs are not transparent, but devious, complex and unpredictable, dates from the Italian Renaissance with its mixture of ruthlessness, ambition, fantasy, failure and self-knowledge given voice by the first modern political thinker, Niccolò Machiavelli.

He then writes a couple of lines down,

Lampedusa’s irresistible creation, the Prince of Salina, a physical giant of a man who unconsciously bends cutlery and crushes ornaments when he is in a dark mood, is a Prince as seductive as Machiavelli’s . . . The Leopard’s dictum that “everything must change so that everything can stay the same” has become an ironic historical maxim quoted again and again to describe Sicily, Italy, the nature of history and the resourceful ways of power.

It would have never approached my mind to compare Don Fabrizio with Machiavelli’s Prince. They couldn’t be starker opposites. Machiavelli’s prince is astute, ambitious, power-hungry. The Prince of Salina on the other hand does not believe that he can trick anyone: He knows he and his family will perish, and accepts this fate idly. He approves of the revolution in Italy, and even turns down the opportunity to have a seat in the new national Senate, for he knows that there is no future for his class and would, therefore, have no constituents.

Yet that is not how some readers interpret him. Even within his existential crisis, the Prince of Salina manages to walk away from a fight he knows is not his to win, but even this action is considered unconsciously cunning. It is almost as though Machiavelli managed to create a long-lasting stereotype of the princely figure that tainted his reputation throughout later years.

Chapter XXIV of The Prince explains that a “new prince,” as opposed to a hereditary one, will win the loyalty of his man more by action than by any obligation to “ancient blood,” for men are more attracted “by the present than the past.” Machiavelli removes the import of tradition and inheritance for the prince, which is why he is able to transform his persona from one who represents “an idea” as Don Fabrizio believes, to one who “appears” to have the qualities of such an idea: A prince must appear “merciful, faithful, humane, religious, upright, and to be so, but with a mind so framed” that he should be able to “know how to change to the opposite.”[1]

We must remember that Machiavelli writes for who the prince should be, not who he is. So, who is the fictional character? The Prince of Salina who represents Tomasi di Lampedusa’s knowledge of his great-grandfather, or Machiavelli’s ideal leader? It is important to make this distinction because it introduces us to the topic of power, the true motive for revolution.

We want to believe that revolutionaries seized power from tyrannical, affluent despots, rather than to admit that the truth about human nature is that we always seek power for ourselves and justify it by heroic, noble means. The critic of The Leopard who compares Don Fabrizio to Machiavelli’s Prince demonstrates as much. But his interpretation of the book is incorrect, and it demonstrates a poor reading of the story that is textually false, implying that the critic either did not read it closely enough or that he read into it what he’s been led to believe about princes and kings.

I want to point out an important, factual error that clouds the rest of the book: It is not the Leopard’s dictum that everything must change so that everything can stay the same. This famous line is actually uttered by the Prince of Salina’s nephew, Tancredi. Tancredi represents the progressive aristocrat in the novel. He sides with the revolutionaries and believes that his house must adopt these new progressive ideas in order to survive. His statement is but one character’s affirmation of the conflict between the past and the present, and it is but one young, ambitious man’s interpretation of his social predicament. The Prince of Salina is much older than Tancredi and sympathizes with his optimism but adopts a different approach.

Don Fabrizio concurs that there is no use in resisting the revolution. He agrees to marry Tancredi, to a noueau-riche lady, Angelica, instead of his own daughter, Concetta. But he does not do this out of any Machiavellian, personal interest. It is Tancredi who wishes to marry Angelica for both her beauty and money, and he persuades his uncle that it would behoove the Salina family to marry into the bourgeois class in order to bring money into the penniless noble family. Machiavelli’s prince, then, is Tancredi. Angelica is the personification of the modern world, which lures Tancredi and even attracts Don Fabrizio from time to time with her charm.

Tancredi wishes to make his story about survival and adaptation, but Don Fabrizio knows it will not be so easy. After all, Tancredi had to enter a universe of “extinct vices, forgotten virtues, and, above all, perennial desire” in order to achieve what he wanted. Here, we can draw inspiration from Machiavelli’s concept of fortuna. We owe half of our actions to our free will, but the other half belong to Fortune.[2] Tancredi decided to seize fortune in order to enter into the new world, while Don Fabrizio’s daughter, Concetta, protested against it and was left with nothing by the end of the novel.

The novel ends with a sense of disquiet and unknowing about which course of action was the correct one. The family dog, Bendico, who was with them from the beginning, dies. Rather than bury him, the family has him stuffed. But, after Don Fabrizio’s death, Concetta cannot bear the sight of the dog. Her unrequited love, Tancredi, has married Angelica and she will now make her debut into a new Italian upper-class society. Concetta is left alone to face a strange world, where her values and past are of little importance. While servants clean the empty palace, she sees her old dog one last time:

As the carcass was dragged off, the glass eyes stared at her with the humble reproach of things that are thrown away, that are being annulled. A few minutes later what remained of Bendico was flung into a corner of the courtyard visited every day by the dustman. During the flight down from the window his form recomposed itself for an instant; in the air one could have seen dancing a quadruped with long whiskers, and its right foreleg seemed to be raised in imprecation. Then all found peace in a heap of livid dust.

These are the last lines of the novel. For a second the dog seems to become the symbol of the family crest, reminding Concetta of that dignified leopard her family once represented, but he then goes back to his current form: Dust. The Leopard is a story about the decline and decay of a noble family and their way of life that can speak to many of us common men who see the dangers of revolutions but, more importantly, understand their inevitability. We can be Tancredi and reject our inheritance for the sake of survival, or we can be Concetta and remain convinced of our righteousness until the world leaves us behind. This is a choice for the youth. When we are old, we may become the Prince of Salina, who must watch it all happen silently and let others make the choice.

What Tomasi di Lampedusa seemed to understand is that oblivion is of our own making: It is the consequence of our tireless desire for power and our never-ending quest to achieve it. History is not a fight with fortune where the losers and their way of life are cruelly cast aside. Wisdom, and peace, comes from knowing when it is our time to hand over the torch. It might not be a hopeful message, but a sobering one. Perhaps Don Fabrizio, and Tomasi di Lampedusa by extension, knew that Machiavelli would have encouraged them to survive. Yet, they did the exact opposite, and in so doing proved to be better judges of history than Machiavelli, for Machiavelli’s understanding of fortune and history turned princes into politicians; Tomasi di Lampedusa, at least, chose to preserve kings as the personification of an idea.

Don Fabrizio said it best himself. During a conversation with Don Fabrizio, a government representative of the new Italy is seeing the social problems in Sicily: Sick children, jobless men, “squalid meals,” and “trembling dogs” in search of food. Disgusted, he declares, “This state of things won’t last; our lively new modern administration will change it all.” The Prince’s internal response is indicative of his knowledge of history and human nature:

All this shouldn’t last; but it will, always; the human ‘always,’ of course, a century, two centuries . . . and after that it will be different, but worse. We were the Leopards, the Lions; those who’ll take our place will be little jackals, hyenas; and the whole lot of us, Leopards, jackals, and sheep, we’ll all go on thinking ourselves the salt of the earth.

This essay was first published here in May 2020.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

Works Cited:

Machiavelli, Niccolo, W.K. Marriot (trans). The Prince.

Tomasi di Lampedusa, Giuseppe. The Leopard. New York: Pantheon Books, 1987.

Notes:

[1] The Prince, Chapter XVIII.

[2] The Prince, Chapter XXV.

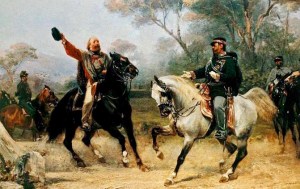

The featured image is Meeting with Victor Emmanuel in Teano (c. 1870) by Sebastiano de Albertis (1828-1897) and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.