Between the potency and the existence… falls the Shadow. These words of T. S. Eliot always come to mind whenever I find myself reading works in translation. The sad fact is that the pure potency of the original work in its original language is lost in its translation to another tongue. And yet, for those of us who are not blessed to be polyglots, the translation is the only way of reading the work. It’s a choice between reading an enshadowed version or remaining completely in the dark. Faced with such a choice, I have chosen to spend much of my time in the shadows in recent weeks.

Between the potency and the existence… falls the Shadow. These words of T. S. Eliot always come to mind whenever I find myself reading works in translation. The sad fact is that the pure potency of the original work in its original language is lost in its translation to another tongue. And yet, for those of us who are not blessed to be polyglots, the translation is the only way of reading the work. It’s a choice between reading an enshadowed version or remaining completely in the dark. Faced with such a choice, I have chosen to spend much of my time in the shadows in recent weeks.

I’ve just finished reading three classic works, recently published in new translations, as well as revisiting an old translation of an obscure work which should be more widely known.

Pan Tadeusz is widely considered to be Poland’s national epic, akin analogously to other national epics, such as The Iliad, The Aeneid, Beowulf, the Poema de Mio Cid, the Chanson de Roland, The Mabinogion or the Orkneyinga Saga. The difference is that this particular epic was not written until the nineteenth century, placing it firmly in the realm of Romanticism, far removed from its classical and mediaeval forebears. Considering its theme of the beleaguered Polish nobility, labouring under the Russian yoke in 1811 and 1812, on the brink of Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion, it invites parallels with Tolstoy’s War and Peace, though its perspective is decidedly Polish and anti-Russian. This new translation by Christopher Adam Zakrzewski (Cherry Orchard Books 2024) renders the poem into prose but is poetic enough to carry a sense of the original’s romantic thrust and passion.

Mr. Zakrzewski is also responsible for the translation of another Polish classic, The Fair Folk and Little Orphan Mary, subtitled “a tale about gnomes”, by Maria Konopnicka, also published by Cherry Orchard Books (2024). Unlike Pan Tadeusz, this classic fairy story has never previously been translated into English. Considering that Konopnicka has been likened to Hans Chrisian Andersen, and that her “tale about gnomes” has been compared with The Wind in the Willows and Alice in Wonderland, Cherry Orchard Books and Mr. Zakrzewski have rendered a great service to the culture of Christendom by making it available in English.

Moving from a couple of classics of Polish literature to a classic of modern French literature, I’ve very much enjoyed Michael Tobin’s new translation of Georges Bernanos’ Diary of a Country Priest (Ignatius Press 2025). Importantly, Tobin’s translation rectifies the significant sins of omission in the only other English translation, which was made by Pamela Morris in 1937, shortly after the novel’s first publication in France. For reasons of her own, probably connected to a prim English prudishness, Morris had failed to translate whole pages of the original work.

The final work in translation that I’ve just finished reading, more than forty years after I had first read it, is History in My Time by Otto Strasser. Translated from the German by Douglas Reed and published by Jonathan Cape in 1941, it surveys German and central European history from the events that led to the First World War until Hitler’s coming to power in 1933. Strasser’s perspective is fascinating, rooted in his personal experiences as a German officer in World War One and his subsequent involvement in radical German politics, first as an ally of Hitler and then as a vociferous opponent. His description of the psychological impact on the exhausted German army of the arrival of the first waves of fresh and well-equipped American troops to the Front in the final months of the First World War are particularly powerful. Equally fascinating is Strasser’s first-hand account in the book’s lengthy introduction of his own efforts to escape from the conquering Nazis following the German invasion of France in the early months of World War Two. Had he been arrested, he would have faced certain death as a well-known and outspoken critic of Hitler who had founded an underground resistance movement against the Fuhrer within the Nazi Party itself.

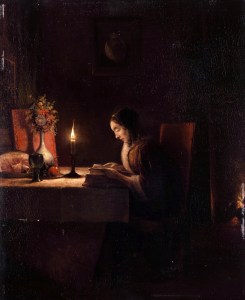

As I think back on the enjoyment and enlightenment that I’ve received in reading these four translated works, I find myself wishing to stand Eliot’s epigram on its head. It’s not enough to say that a translation is a mere shadow of the original work. Although it does not shine as brightly, it has a light of its own that brings a gleaming to the gloaming; it is a glimmering candle that brings a previously unreadable book to light and therefore to life. Between the potency of the unseen thing in the dark and the existence of the translation falls the shadow caused by the enkindled light.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Reading by Candlelight” (by 1870), attributed to Petrus van Schendel, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.