In the drama of the two brothers and the loving Father the heart of the Gospel is laid open before us. Human freedom and divine love are here. Human sinfulness in two of its more dramatic forms—dissipation and contemptuous pride—are on view. We are warned about the reality of sin and brought face to face with divine mercy.

Today’s Gospel is a magnificent example of storytelling. Luke calls it a parable and it is, but it is longer and more detailed than most of Jesus’ parables. Most are simple comparisons: the Kingdom of God is like a mustard seed, or a shepherd who lost one sheep. They are beautiful and powerful. But this story of the prodigal son, the welcoming father, and the elder brother draws us in with scenes covering a considerable length of time. It draws us in like a good novel or a good movie, yet it is less than five hundred words long. It has captured the imagination of Western civilization, especially in art but also giving us the cliché of the prodigal son and the common image of slaughtering the fatted calf.

Today’s Gospel is a magnificent example of storytelling. Luke calls it a parable and it is, but it is longer and more detailed than most of Jesus’ parables. Most are simple comparisons: the Kingdom of God is like a mustard seed, or a shepherd who lost one sheep. They are beautiful and powerful. But this story of the prodigal son, the welcoming father, and the elder brother draws us in with scenes covering a considerable length of time. It draws us in like a good novel or a good movie, yet it is less than five hundred words long. It has captured the imagination of Western civilization, especially in art but also giving us the cliché of the prodigal son and the common image of slaughtering the fatted calf.

Considered in utterly human terms, Jesus is a great storyteller. We know him therefore not just as Master and Savior but as Teacher. And never is he more teacher than in this story, designed to respond to some people who, like the elder brother who resents his father’s love for his prodigal younger brother, disapprove of the company he keeps.

So, in the first instance the story reminds us of God’s particular love for the fallen, the strayed, and the lost. It’s not that he loves those of us who tack nearer to the straight and narrow any less, but the sick have need of a physician, not the healthy. And so, Jesus spends a lot of time with those on the margins of society. We must do no less.

It’s important to remember the setting, the context of the story. While it is told to explain why he keeps such bad company, we also need to look with care at each of the three characters in the drama—the two brothers and the father.

The traditional name of the story is of course the Parable of the Prodigal Son, and he is indeed the protagonist. His actions set off the drama. And his actions are sad and reprehensible. He wants his share of the estate now. Many of us have adult children and others of us are adult children with surviving parents, but we all know what this means. To want his share of the estate now is in effect to wish the old man dead. Then as now it was a violation of decency, respect, and custom. Note also that it is a violation of the Fourth Commandment, which minimally requires children to look after their parents in their old age—not to wish to be rid of them. The relevance to the assisted suicide movement is obvious, but dramatically, the account informs us at the beginning that the younger brother is a nasty piece of work.

And so off he goes, squandering his inheritance in a “life of dissipation”—details omitted. He has sought, as so many of our contemporaries have sought, to escape limits, to fulfill his every desire, and to be free of the consequences of his behavior. He misunderstands the meaning of humanity and maturity as the right to do whatever he wants to—and like so many in our culture, walks right into slavery. And into the pigpen. Jesus has cleverly described the ultimate degradation for a Jew.

Then there is the father, and while it is obvious that he represents God, just as the prodigal represents humanity in the depths of sin and revolt against God, we need to reflect on what Jesus says about the father in order to benefit from the portrayal.

The father gives the son a long leash. He actually indulges the son’s selfish and wicked request. Here’s the money. God himself is similarly extravagant. He has poured his blessings upon us—including those limits we know as his law and which are there for our good. And he gives us a long leash, so that we might love and serve him freely rather than by constraint. That’s what the prodigal will learn in the end.

The long leash is not a matter of indifference on God’s part or on the part of the father in the drama. It too is a sign of love, an opportunity for dignity, an opportunity to respond in freedom to the love that moves all things. God gives us the freedom to say yes or no, to serve or to rebel, so that we might respond to him in a fully human manner.

Like the father in the story, he gives us a long leash but never gives up. So, when the prodigal drags himself home hoping to be nothing more than a servant, the father is waiting and watching. That is why some call it the Parable of the Waiting Father. There are few points that Jesus reiterates more often than the readiness of God to receive and forgive. And there is no more direct reminder of God’s mercy than the account of the father and the prodigal.

Like the father in the story, he gives us a long leash but never gives up. So, when the prodigal drags himself home hoping to be nothing more than a servant, the father is waiting and watching. That is why some call it the Parable of the Waiting Father. There are few points that Jesus reiterates more often than the readiness of God to receive and forgive. And there is no more direct reminder of God’s mercy than the account of the father and the prodigal.

And then there is the elder brother, whose role in the drama is the one that is most likely to accuse and trouble us. There probably are not many prodigals among us. To be sure, the Church through its history has welcomed many from lives of unbelief, self-destruction, and dissipation. You may know some, and you’ve all heard of the conversion of St. Augustine. But most of us have avoided the path of the prodigal son for most of our lives—out of fidelity, out of good examples set by out parents and others, or even out of fear.

We have most in common with the elder brother, not the welcoming father, though at times we have the opportunity to welcome those who have come to the faith or returned to the fold. Like most priests, I have had some such experiences in the confessional.

But truth to tell, we are mostly in the position of the elder brother—we stayed home, stayed close, and did the right thing. That’s not bad! It is by far the better idea—so long as we do not fall into the elder brother’s trap of resenting the prodigal and his father’s exuberant response to his return. The elder brother has forgotten what his father tells him so lovingly:

My son, you are here with me always; everything I have is yours. But now we must celebrate and rejoice, because your brother was dead and has come to life again; he was lost and has been found.

The elder brother had a good deal. We who have served long and hard have not been cheated by the prodigals or by the less devout and faltering. We have had a good deal: everything that belongs to the father is ours.

In the drama of the two brothers and the loving Father the heart of the Gospel is laid open before us. Human freedom and divine love are here. Human sinfulness in two of its more dramatic forms—dissipation and contemptuous pride—are on view. We are warned about the reality of sin and brought face to face with divine mercy.

The father watches and waits. He watches and waits for a fuller response from us. He is eager to forgive our sins, great or small. Lent’s call to the Sacrament of Confession is one part of the call to step deeper into God’s love and into the profound truths about God and the world set before us in this ancient piece of Jewish storytelling, less than five hundred words long. And we are reminded that the Son of God took the role of the prodigal, going into a far country to bring us back to the waiting and welcoming Father.

__________

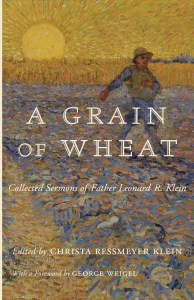

This essay is taken from A Grain of Wheat.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “The Return of the Prodigal Son” (1862), by James Tissot, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.