I JUST did something depressing and read the entire text of Starmer’s speech to the workforce at Jaguar Land Rover last week. (I do these things so you don’t have to, but it you’re feeling masochistic follow this link.) Aside from the ghastly English, the dull prose and the revelation that the Toolmaker’s Son’s father has now been promoted to an engineer (he actually owned the toolmaking company; inconvenient facts don’t matter to an ex-lawyer like Two-Tier), the speech comprised soundbites and an unlikely claim that his was a government of industrial renewal. There was no indication of how his government would deliver that renewal.

Words are cheap

That’s a shame but unsurprising. Neither he nor the cabal of Marxists that comprise his cabinet understand engineering or economics. His trip to (Tata owned) JLR was in response to the American 25 per cent car import tariff and was a platform for him and Rachel Reeves to demonstrate their care for British industry to the press. JLR’s CEO had already been in Downing Street demanding support for JLR, its 9,000 jobs and the 200,000 jobs JLR supports in its supply chain. That last figure is a bit hookey, both in its calculation and the definition of ‘support’, but of course it is a big number that our numerically challenged PM and Chancellor can grasp. Hence the visit.

One of the jobs of a CEO is to raise money as cheaply as possible and to influence the political climate in the company’s favour, so chapeau to Adrian Mardell for beating his competitors to grab the PM’s ear. One of the duties of a Prime Minister (in his capacity as First Lord of the Treasury) is to spend taxpayers’ money wisely. Like all Prime Ministers since John Major, Two-Tier doesn’t have any government funds as the Second Lord of the Treasury (Rachel from customer service) is trashing the economy, helped by mad Ed, the lord of misrule in the Department for Energy Security and net zero.

Two-Tier therefore didn’t promise JLR cash – yet. Instead he promised to back them (and the rest of the remnants of British industry) ‘to the hilt’. Then he simply announced some shuffling of the deckchairs on the Titanic that is his government’s policy; the electric vehicle (EV) targets will be adjusted in the hope that no fines will have to be levied.

Electric vehicles aren’t loved

The EV target is intended to force manufacturers to sell more EVs. The idea was introduced by Boris Johnson who, drunk with the power of imprisoning the entire nation, decided that the customer was not to be allowed the freedom to buy what he or she wants. Presumably he (or his wife, or Dilyn the dog) thought that the Behavioural Insights Team (the Downing Street propaganda unit introduced by David Cameron) could persuade British car buyers like you to want EVs. It hasn’t worked out that way; Britons like EVs no more than they like heat pumps.

Before the American tariffs the target for EV sales in 2025 was 28 per cent but the actual sales were under 20 per cent, meaning that car manufacturers are in line for £6billion of probably unaffordable fines. Or rather they would have been (at £15,000 per car sold) but for some nifty policy footwork and some creative accounting.

While the fleet operators were keen on EVs to meet their DEI targets, consumers are less impressed. Worse (for the target), many of the lefties who believe in net zero are falling out of love with Tesla since Elon Musk became part of the Trump administration. Now, in a redefinition that would impress Stakhanovites, hybrids have been reclassified as battery vehicles for another five years. On the other side of the equation, to hit the targets the manufacturers’ other option is to reduce petrol and diesel car production – which might explain the JLR decision to suspend sales to America. (Only 8 per cent of new car sales in the US are electric, so that’s effectively reducing JLR petrol and diesel sales by 24 per cent).

However tinkering with the targets is missing the point. EVs are far from universally loved. As well as range concerns, the depreciation costs, the challenges of installing home chargers and the belief that EVs spontaneously combust (they might not) mean 80 per cent of people don’t want them. So desperate is the government to increase EV take-up that they’re considering reintroducing EV purchase subsidies. If that happens, you and your grandchildren will pay through the ever-increasing national debt.

It’s not just car manufacturers

The problems of British industry reach far beyond what’s left of the car industry. Making stuff in the UK is becoming increasingly expensive due to soaring land prices, increasing capital costs, extortionate energy costs and increasing labour costs. The latter two are a direct result of this government’s benighted policies and could be altered with a stroke of a pen.

The Cabinet are belatedly becoming aware of the ruinous costs of net zero. (Brazen plug: they should have read my book – Richard Tice did). Unfortunately they also believe in internationalism, the Climate Change Act and global warming so it won’t abandon net zero. Mad Ed, the man who can’t eat a bacon sandwich, also holds great sway in the Labour Party – which is remarkable giving his leading them to electoral annihilation in 2015. Marxism runs deep on the Labour left and Ed is Marxist royalty. Vince Dale, one of Labour’s biggest donors, made his £100million fortune out of green energy. His voice is listened to by the Miliband satraps.

Reversing the increases to employers’ National Insurance would cost the Treasury £25billion a year, which would increase the UK’s deficit to about £175million a year. That might or might not give the ONS the vapours and upset the bond markets, increasing the government’s borrowing costs, so Two-Tier probably can’t do that either.

Reducing the cost of commercial capital is more of a long-term project and government is not directly involved. The one thing that it could do is reduce the taxation of corporate profits. That would (in theory) increase the net return on investment in a UK company which should trickle through to lower capital costs for the same risk. Of course, President Trump’s rewriting of the rules of international trade (which may or may not be permanent) has increased risk until the financial and corporate worlds get used to the new normal.

The other helpful thing that Two-Tier could do would be to end the war on non-doms (many of whom make private capital investments in private UK companies). They’re fleeing the UK at record rates, taking their capital with them. Whether they will continue to invest in UK companies from overseas is an open question. Investing in companies is a route to getting a visa but so is buying bonds, which are frangible and have a liquid market, along with a government that is set on selling ever-increasing amounts of them until it can balance its budget.

There is almost nothing the government can do to reduce land prices. Even if it could, a fall in the value of land would cause further financial chaos.

So the government’s support for industry is reduced to its usual stock in trade: photo opportunities and soundbites. That’s no basis for any effective policy, let alone one to build the economic growth that this country desperately needs to escape the toxic legacy of 25 years of misrule.

This is Reform’s opportunity. It’s the only party to have renounced net zero. It’s the only party to have realised that certain industries are fundamental to creating and maintaining wealth in the UK. That doesn’t make it easy. Axing net zero would immediately reduce electricity costs and (if it relaxed industrial emission requirements) make the production of primary steel in the UK possible. Reform is also the first party to have called for the nationalisation of British Steel Scunthorpe.

Following the closure of the blast furnace at (foreign-owned) Port Talbot, the last ones, at Chinese-owned Scunthorpe, are under threat – presumably Jingye Group finds it cheaper to make steel in China and ship it here. It’s possible that Jingye purchased British Steel simply to shut down a competitor, keeping its customers and distribution while deleting its expensive manufacturing. Remember, companies (rightly) exist to make a profit, not throw shareholders’ money at maintaining complex (expensive) capital equipment that can’t deliver product at the global price.

That means that unless the emissions legislation eases and the energy price falls, no commercial company will buy the Scunthorpe works. While the economic purist would argue that letting the industry die in Britain is what Adam Smith would have advocated as it’s less efficient than in other countries, that comes with supply chain insecurity and the loss of skills. Once a workforce are laid off they get other jobs. BAE systems found this out when the Royal Navy had a break in its submarine construction programme. In their words, they forgot how to build submarines. The net result was delays and massive cost overruns on the construction of HMS Astute. (BAE have now recovered their institutional memory and their submarine construction capability is expanding. You paid for it).

The loss of institutional knowledge extends down the supply chain too; reversing the closure of an entire industry is non-trivial. Preventing that closure can only be achieved by nationalisation, as Reform advocated last week and Parliament is considering today.

Nationalisation is no panacea

Of course there are two problems with nationalisation. Firstly the government has no money, so the national debt will increase. Secondly no one in the government understands how to run a business, let alone a steel manufacturer. That means that at best losses will continue at the current level, putting the taxpayer on the hook indefinitely – or at least until it ditches net zero. Don’t hold your breath.

However at least keeping the industry going preserves the workforce and supply chain until a more enlightened government changes energy policy, recognises the importance of strategic industries and develops an economic model that can make British steel-making profitable. That might include tariffs on imported steel. That enlightened government could then return the works to the private sector to recoup at least some of the taxpayer’s costs while retaining a golden share precluding foreign ownership. None of that is straightforward, and it is entirely contingent upon third parties in the private sector, which the Labour Party don’t understand – particularly in their current form. Overall nationalisation is a lesser evil than losing a key national capability; it keeps the capability alive while the taxpayer and voter try to work out what sort of country they want to live in.

The further problem is how to build capital markets that can provide UK-domiciled capital to invest in the privatisation of the nationalised British Steel. Without them, as the nationalised industries of the 1960s and 1970s (including British Steel) discovered the hard way, investment capital will always be competing with the NHS, welfare, defence and the rest of the compelling cases that the government machine presents to the Treasury in each spending round. Voters are understandably more concerned about hospital beds than blast furnaces, which is why nationalised industries always end up under-capitalised (and therefore inefficient). That doesn’t matter to the Marxists; it should matter to Reform.

That leads inexorably to the challenge of whether it is possible to wean the capital markets off their inherent short-termism. As all investing is risky, making a profit in the short term is often a better strategy than sticking in for the long term, especially for investors whose bonus (and thus their family’s quality of life) is driven by annual results. A week in politics is a long time and a year in the City is almost eternity. For a capital-intensive industry, investment payback inside a decade is close to a miracle. That makes it a hard sell to the capital markets, which means that capital is expensive.

So it’s not just globalisation that isn’t working. The whole structure of Western free market capitalism has gone awry. President Trump’s tariffs are an inevitable consequence of that. Economists might be right when they argue that isolationism and autarky aren’t the answer, but if the status quo is unacceptable, perpetuating it is lunacy. Creating a new economic model is a political imperative for libertarian Western free market capitalists, not least because it’s probably the only way to avoid civil unrest. Market turbulence is a small price to pay.

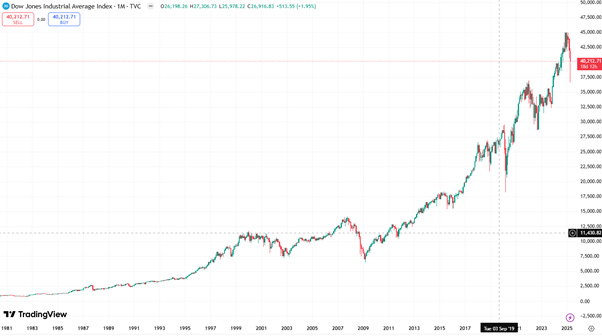

And yes, the recent hiatus is simply turbulence, as the 30-year chart of the Dow Jones Index shows (courtesy of Trading View).

The Dow’s current level is the same as it was in February 2025, which was an all-time high. It’s only one measure and possibly not the most important one, but the tariffs have not caused a financial meltdown. Some in the financial services have complained about soaring US Treasury Bond Yields. The chart below from Trading Economics shows some context:

The hedge fund and private equity industries got used to cheap money. That was a delusion, largely funded by the taxpayer who underwrote the magic money tree of quantitative easing. If the price of recreating an economy that works for everyone is the demise of the self-aggrandising hedgies and private equity players, so be it. They didn’t really exist until the late 1990s; the Thatcher and Regan booms were delivered without them. I suspect the UK would be a better place without them. They are whining – but out of self interest (which is what they do best).

Brace for turbulence but don’t panic.

This article appeared in Views From My Cab on April 12, 2025, and is republished by kind permission.