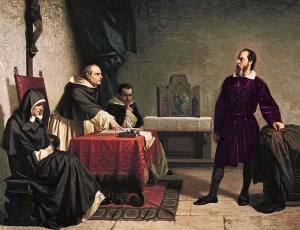

The affair of Galileo was not played out in the atmosphere of inquisitorial terror that some writers have imagined; one cannot even say that the high ecclesiastical authorities posed systematically as enemies of scientific progress.

How did the Church react in face of perils she could not ignore? The secular arm, whose aid she had the power to invoke, provided her with a formidable weapon of coercion and repression, and of this she made full use. The Inquisition, devised long ago to withstand the menace of intellectual revolt, took action wherever it continued to exist. It had already struck a number of resounding blows. Giordano Bruno, arrested at Venice and handed over to the papal authorities, was condemned as a heretic and burned on the Campo dei Fiori, where his statue stands today. Vanini too was put to death, his tongue torn out by the executioner. Campanella was more fortunate; he was merely obliged to leave Rome, and died peacefully in the Dominican house of Saint-Honoré at Paris. At the request of the religious authorities, Louis XIII began his reign by signing the decrees of 1617 against irreligion and blasphemy, as a result of which Théophile de Viau suffered imprisonment.

How did the Church react in face of perils she could not ignore? The secular arm, whose aid she had the power to invoke, provided her with a formidable weapon of coercion and repression, and of this she made full use. The Inquisition, devised long ago to withstand the menace of intellectual revolt, took action wherever it continued to exist. It had already struck a number of resounding blows. Giordano Bruno, arrested at Venice and handed over to the papal authorities, was condemned as a heretic and burned on the Campo dei Fiori, where his statue stands today. Vanini too was put to death, his tongue torn out by the executioner. Campanella was more fortunate; he was merely obliged to leave Rome, and died peacefully in the Dominican house of Saint-Honoré at Paris. At the request of the religious authorities, Louis XIII began his reign by signing the decrees of 1617 against irreligion and blasphemy, as a result of which Théophile de Viau suffered imprisonment.

There was thus a decided reaction to the perils with which irreligion was menacing the faith. But these coercive measures were not altogether effective. They were frustrated by the connivance which godlessness found for itself in the most varied circles, not least in high places; even during the Quattrocentro there had been popes who showed remarkable indulgence towards atheistic humanists. Furthermore the Holy Office, though capable of punishing open nonconformity, seems to have been less efficient when called upon to silence men whose scepticism lay beneath the surface of their writings. Rabelais, for instance, was able to publish his works with almost complete impunity, and Montaigne was requested to do no more than revise his own Essais. Finally, we may ask whether the steps taken by the Inquisition were well chosen, whether they invariably served the cause of truth and the interests of the Church.

This question is prompted by a famous episode which involved one of the most celebrated figures of the early seventeenth century—Galileo. The affair, as we know, has been tirelessly exploited against the Church; anti-clerical polemists have elected to charge her in this matter with obscurantism and ferocity. We are all familiar with the picture of a brilliant scientist imprisoned for his discoveries and stigmatizing his judges in the eyes of posterity with a few devastating words. That picture, however, is not altogether accurate. Galileo was born at Pisa in 1564. His scientific endowments were manifest from youth upwards, and in 1592 he obtained a chair in the University of Padua. Possessed of a lively mind, curious and keenly interested in the visible world about him, he devoted much of his time to studying the stars, with particular reference to the problem of their movement. At that time the accepted explanation was the Ptolemaic theory derived from Aristotle and propounded some fourteen centuries earlier. According to that theory the earth was at rest in the centre of the universe, and all else, stars and planets alike, revolved about it. The Bible was held to contain numerous passages which confirmed this view; not only the famous episode of Joshua halting the sun, but also several verses of the Psalms (103:5) and Ecclesiastes (1:4, 6), where the immobility of the earth and the mobility of the sun were expressly stated. During the fifteenth century, however, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa had advanced the contrary hypothesis, which had been taken up and developed by Canon Copernicus in the sixteenth: the sun does not revolve; the earth and all the planets do. But that was a mere hypothesis, put forward as such by its authors, which science could not as yet confirm by demonstration. In Germany it had been resolutely opposed by the Protestant leaders, Luther and Melanchthon; Pope Clement VII, on the other hand, had treated it more favourably, and none of his eleven successors had seen fit to contradict it.

This question is prompted by a famous episode which involved one of the most celebrated figures of the early seventeenth century—Galileo. The affair, as we know, has been tirelessly exploited against the Church; anti-clerical polemists have elected to charge her in this matter with obscurantism and ferocity. We are all familiar with the picture of a brilliant scientist imprisoned for his discoveries and stigmatizing his judges in the eyes of posterity with a few devastating words. That picture, however, is not altogether accurate. Galileo was born at Pisa in 1564. His scientific endowments were manifest from youth upwards, and in 1592 he obtained a chair in the University of Padua. Possessed of a lively mind, curious and keenly interested in the visible world about him, he devoted much of his time to studying the stars, with particular reference to the problem of their movement. At that time the accepted explanation was the Ptolemaic theory derived from Aristotle and propounded some fourteen centuries earlier. According to that theory the earth was at rest in the centre of the universe, and all else, stars and planets alike, revolved about it. The Bible was held to contain numerous passages which confirmed this view; not only the famous episode of Joshua halting the sun, but also several verses of the Psalms (103:5) and Ecclesiastes (1:4, 6), where the immobility of the earth and the mobility of the sun were expressly stated. During the fifteenth century, however, Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa had advanced the contrary hypothesis, which had been taken up and developed by Canon Copernicus in the sixteenth: the sun does not revolve; the earth and all the planets do. But that was a mere hypothesis, put forward as such by its authors, which science could not as yet confirm by demonstration. In Germany it had been resolutely opposed by the Protestant leaders, Luther and Melanchthon; Pope Clement VII, on the other hand, had treated it more favourably, and none of his eleven successors had seen fit to contradict it.

The young professor at Padua encountered the ideas of Copernicus and made them his own. The telescope had been invented in 1608 by the Dutch optician Lipperochy; Galileo constructed one which magnified surfaces nine hundred times and enabled him to observe the phases of the moon, the satellites of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn and many other striking phenomena of outer space. In 1610, in his Nuntius Sidereus (Messenger of the Stars), he informed the public of his astonishing discoveries. In 1611, while studying Jupiter, he believed himself to have hit upon scientific proof of the Copernican theory. He went to Rome and was welcomed with extraordinary marks of favour: Pope, prelates and princes, all were anxious to hear about the wonders of the heavens.

Nothing untoward would have happened if Galileo had confined himself to the field of science. But having been attacked by various adversaries and accused of denying the truths of Holy Scripture, he undertook, with the help of two tactless pupils, to enter the field of biblical exegesis and show that the new system was in perfect accord with the sacred text. His arguments were considered by Pope Paul V to be strongly infected with the principles of free judgment upheld by the Reformers. The Holy Office was alarmed and in 1616 condemned the two fundamental propositions of the system, that the sun is the centre of the world and the earth is in motion. Galileo, though not named, was required to abandon the condemned thesis, and he at once declared his unqualified readiness to submit to the judgment of authority. None of his writings was placed on the Index, and the Pope most generously declared that he himself would protect him against his detractors.

Years passed. Cardinal Barberini became Pope. He was a friend and warm admirer of the scientist, and had even dedicated to him a Latin ode. Galileo, haloed thus with glory and continuing his labours undisturbed, perhaps believed that the time had come to have the decisions of 1616 revoked. At all events, he was attacked by a Jesuit, Father Grassi, and replied with a polemical work: Il Saggiatore (The Essayist), which he dedicated to the Pope and to which Mgr. Riccardi, Master of the Sacred Palace, granted an imprimatur. Encouraged by success, he proceeded to write an enormous work entitled A Dialogue on the Two Greatest Systems of the World (1632), in which he formally declared the Copernican view to be the sole scientific and demonstrated theory. To this work Mgr. Riccardi was not prepared to grant his imprimatur unless it were preceded by a preface that would represent the system as a mere hypothesis. Galileo refused.

The affair was envenomed not only by the astronomer’s enemies, who denounced him to the Inquisition for having violated the undertaking he had given in 1616, but also by his friends and supporters. Campanella, for example, foolishly involved the Pope by informing all and sundry that “Simplicius” in the Dialogue, the ridiculous opponent of the Copernican theory, was in fact Urban VIII—which was quite untrue. The trial before the Holy Office (1633) dragged on for several months; during which time Galileo, instead of being detained in prison, was authorized to stay with a friend. Two charges were brought against him: (1) that he had expounded the condemned thesis, declaring it to be scientifically established, and (2) that he had adhered to it in foro interno. Despite a threat of torture, he resolutely denied the second charge, a denial which he still maintained when confronted with his work. Nevertheless he was “gravely suspect of heresy,” and on June 22 he received sentence in the Dominican Convent of the Minerva. His Dialogue was banned; he himself was ordered to read, kneeling, a precise formula of abjuration, to recite the seven penitential psalms each week for three years and to remain in prison for the remainder of his life. This last clause of the sentence, however, was interpreted in the most generous fashion, for until his death (1642) he was allowed to reside either in the palazzo of his friends the Piccolomini at Siena, or in his own villa at Florence, where, as he was fond of saying, he “offered willing sacrifice to Bacchus, without forgetting Venus and Ceres.” He lived as a good Christian, too, never seeking to rebel in public against the judgment that had overtaken him.

The affair of Galileo then was not played out in the atmosphere of inquisitorial terror that some writers have imagined; one cannot even say that the high ecclesiastical authorities posed systematically, a priori, as enemies of scientific progress. If Galileo (and this applies even more to many of his supporters) had not implied, or even expressly declared, that the new astronomy negated the biblical text, the second trial would have been avoided. It is, however, none the less true that the attitude taken by the Holy Office in this matter is open to criticism. It was doubtless impossible, in the climate of that age, for official theologians and exegetes to acknowledge any but the literal meaning of the sacred text, even in its smallest details. The Protestant churches, and the very Synagogue itself, had adopted exactly the same view. But the inquisitorial court, by taking its stand in the realm of scientific fact and presuming to forbid belief in the rotation of the earth, placed the Church in an untenable position and made her look absurd in scientific eyes, even though the doctrine of her infallibility was not in this instance at stake. We shall unfortunately discover the same opposition to scientific progress in the subsequent history of Christian apologetics. On the other hand, it does not seem that Galileo’s judges detected the most dangerous threat of his ideas. The whole of his defence was based ultimately upon a formula which can be expressed as follows: “The Bible says one thing; my eyes have seen something quite different.” He sought to draw a hard and fast line between the domain of faith and that of experience. But such a line was going to hallow the divorce between faith and science, revelation and reason. It was possible to condemn Galileo if he treated Holy Scripture with contempt. But it should also have been explained why the scheme of divine inspiration and that of scientific discovery did not coincide, and how theology was quite compatible with science. No such explanation, however, was forthcoming at that date.

This essay is taken from The Church of the Classical Age: The Era of Great Splintering, Volume 1.

Republished with gracious permission from Cluny Media.

Imaginative Conservative readers may use the code IMCON15 to receive 15% off any order of not-already discounted books from Cluny Media.

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is “Galileo facing the Roman Inquisition” (1857), by Cristiano Banti, and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.