The idea of kingship, which the ancient cultures understood, is necessary for us to own as well. It is a necessary part of the Christian imagination, not to be cast aside simply because literal kings form little or no part of our experience.

Eschatological questions have been on my mind lately, as it seems to me that we should all have an idea of where we are going. I have been fortunate to find some very lucid thinkers on these weighty topics. I have mentioned before the British theologian N.T. Wright, who has done such important work on the “kingdom of God” motif in Christianity. Wright identifies “the kingdom of God” as the principal idea of the New Testament, declaring that the basic narrative of scripture as a whole (what we call salvation history) can be described under the heading of “How God Became King.”

Eschatological questions have been on my mind lately, as it seems to me that we should all have an idea of where we are going. I have been fortunate to find some very lucid thinkers on these weighty topics. I have mentioned before the British theologian N.T. Wright, who has done such important work on the “kingdom of God” motif in Christianity. Wright identifies “the kingdom of God” as the principal idea of the New Testament, declaring that the basic narrative of scripture as a whole (what we call salvation history) can be described under the heading of “How God Became King.”

The Kingdom of God is a phrase that sums up what God is working in the world, the purpose for which Christ came and the consummation of God’s plans for the universe. Yet the idea has a lesser profile today. Where do we find it? We repeat the words in the prayer Jesus taught us: “thy kingdom come, on earth is it is in heaven.” The old familiar phrase “till kingdom come” is a remnant of the importance the idea of God’s kingdom once had in our imagination. And we find it throughout the liturgy. For example, in the Liturgy of the Hours for the current month I find this prayer:

“You make all things new, and command us to wait and watch for your kingdom, grant that the more we look forward to a new heaven and a new earth, the more we may seek to better this present world.”

In spite all these reminders, the kingdom of God remains a somewhat forgotten doctrine, even though it was one of the phrases most frequently on our Lord’s lips. “Heaven” remains more central to our pious rhetoric than the kingdom of God, and our idea of heaven tends to be quite flat. We even absentmindedly confuse the two concepts, saying “kingdom of heaven” but meaning by this a disembodied “afterlife,” not understanding that “kingdom of heaven” in Matthew’s Gospel is simply a reverent circumlocution for “kingdom of God.” All that reigns in this particular kingdom is confusion, caused by the considerable changes in language between the 1st and 21st centuries.

As Wright emphasizes again and again, the main goal of Christian life is not “to go to heaven when we die” but to build up God’s kingdom. He reminds us that we believe in a two-stage future life for the blessed: peaceful rest with God after death, followed by a New Creation in which “new heavens” and a “new earth” will come into being.

Christian writers ancient and modern have written about the reality of the kingdom of God. But “kingdom theology,” as it has been called, has met with resistance, in part because some people think they smell in it the liberal myth of progress. The idea that the kingdom of God is coming on earth is surely a secular utopian idea, the province of political radicals and revolutionaries, dictators and tyrants. Whereas we know that in reality Christianity is all about the “soul” and “heaven” and other “spiritual” matters.

Wright meets this objection head on. He acknowledges that “kingdom of God has been a flag of convenience under which all sorts of ships have sailed.” These include programs of social improvement or political revolution, aimed at bringing a utopia to earth. Nineteenth-century philosophies such as G. F. Hegel’s envisioned history as an inexorable unfolding of the divine spirit leading inexorably to a glorious goal for humanity.

But such philosophies are corruptions the original meaning of the kingdom of God. Wright states, “the fact that some people, and some movements, have misappropriated the kingdom theology of the gospels doesn’t mean that there isn’t a reality of which such ideas are a caricature.” And what is the difference between the original vision of the kingdom of God and the modern secular vision of progress? In a word, it is the difference that God makes. In the secular version of progress, God is basically incidental. Humanity can achieve perfection by itself, through its own resources of education, science, technology, and hard work; we do not need God’s grace or grace’s conduit, the Church.

In the Christian vision, by contrast, God is bringing his own kingdom about through man’s cooperation. It is a matter of relating to and loving God as our origin and final end. And the true kingdom of God is not a blind and inexorable process but a fully willed project that is an expression of a divine Personality.

Another reason we resist the idea of the kingdom of God is the very word “kingdom.” It is a hard concept for a modern democratic society to relate to. Also, it sounds political, and we are taught that what Jesus came to do was not “political” but “spiritual.” One of the points that Wright makes is that the categories “spiritual,” “religious,” “political,” etc. are to a large degree modern constructs that people in Christ’s time would simply not have understood. They saw reality as a unity where we see only fragmented parts. So while there is indeed a sense that Jesus was “not political” (in the narrower, modern sense of the term), the fact remains that his mission was to proclaim God’s universal reign. “Kingdom of God” (or “Kingdom of Heaven,” which means the same thing) is among the phrases most used by Jesus himself in the Gospels. The people that were scattered abroad and left to their own devices would now be brought under God’s sovereign rule, so that (in the words of St. Paul) God would be all in all. When Jesus told Pilate that his kingdom was “not of this world,” he meant that his kingdom does not operate according to the norms of fallen humanity: pride and the lust for power. Instead, his kingdom was one of self-giving love and service. To that extent, as Wright argues, while his kingdom was not of this world, it was emphatically for this world—this world with its complex mixture of spirit and matter, of sense and intellect. Nothing could be more wrong than to impose a Platonizing interpretation on Jesus’ words, in which our destiny is to fly away into a “purely spiritual” realm. Suffice it to say that the actual kingdom of God that Jesus preached is far richer than either the technological utopia envisioned by modernity or the “purely spiritual” heaven imagined by a Platonizing piety.

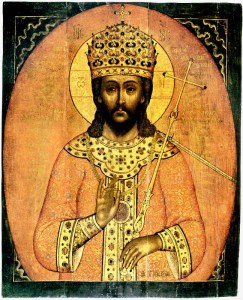

The idea of kingdom and the idea of a king go hand in hand. The image of Christ as king was vital for the early Christian community, who exalted Christ as the true King whose power overruled that of any earthly ruler, Caesar or otherwise. The kingship of Christ was one of the things that made the early Christians so troublesome to the empire and led to so much martyrdom in the first few centuries. By declaring Christ as king, the Christians were putting their lives on the line.

Christ is unapologetically a king and was seen as such from the first. But what kind of king is he? Not the prideful king who lords it over his subjects, but the good king who empties himself in service to his subjects, to save and rescue them. The point is not to counterpose the “material” and “spiritual” worlds, or the “political” and “religious,” but rather to recognize that reality must be looked at from the right point of view, centered in God.

And Jesus inaugurated his kingdom, not with victory or success as the world understands those terms, but through a Cross. When we gaze upon a crucifix, we see a sort of billboard advertising Disaster on the most monumental scale. The cross was the ultimate symbol of defeat, but Christ wrenched it into the ultimate symbol of self-giving love, proving himself the greatest king of all.

The idea of kingship, which the ancient cultures understood, is necessary for us to own as well. It is a necessary part of the Christian imagination, not to be cast aside simply because literal kings form little or no part of our experience. If it helps, we could think of Jesus and his apostles as a new president and his cabinet, or a new pope and his college of cardinals, putting in motion an astonishing new regime.

At the beginning of the Acts of the Apostles, St. Luke recapitulates Jesus’ Ascension. The apostles ask Jesus, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” Interestingly, Jesus does not correct them. He answers their question straightforwardly, and gives them further instruction: “It is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has fixed by his own authority. But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the end of the earth.” The disciples’ idea was not wrong; Jesus was in fact going to “restore the kingdom to Israel,” though not in the way they expected. Their idea needed to be redirected, widened, but at bottom it was correct; Jesus was a king, and he was going to establish a kingdom. We are at a place where language is no longer mere metaphor but becomes transcendent fulfillment. Jesus is a true king, and his kingdom is a true kingdom.

Sometimes the peoples of the ancient world enjoyed the presence of a king; other times, like the Israelites for a large part of their history, they lacked and longed for a king. Kingship was a central symbol of peoplehood and belonging, binding everyone together. The first Christian disciples saw in Jesus the fulfillment of all the Israelites’ longing for a king. The title “Messiah” or “anointed one” has definite kingly implications, such that Wright even goes so far as to translate Christ’s title as “King Jesus.”

The doctrine of the Kingdom of God answers a real human need. We all need to feel as if our lives are meaningful on a larger scale, that what we do had eternal significance. It is one of the reasons why people have been so ready to believe prophets promising coming kingdoms that are clearly not of God. But despite the many false kingdoms promised, the authentic kingdom remains, and it should be every bit as central to our belief as it was for Jesus. To those who look at the world and say, “Where is the evidence for the kingdom of God?”, the answer is that the kingdom is very gradually taking shape, just like the mustard seed in the parable. Despite the continued presence of evil and suffering, the birth of the Church has made a tremendous difference in the world, morally, politically, aesthetically, and in a hundred other ways. The kingdom does not come at once but grows slowly and steadily (but we should also be on the lookout for sudden, great manifestations of God’s power). This kingdom is built by God through the cooperation of human beings. It will include, ultimately, the elimination of sin and death and new life in resurrected and glorified bodies.

__________

The Imaginative Conservative applies the principle of appreciation to the discussion of culture and politics—we approach dialogue with magnanimity rather than with mere civility. Will you help us remain a refreshing oasis in the increasingly contentious arena of modern discourse? Please consider donating now.

The featured image is Царь царём (a 17th-century icon from Murom), by Aleksandr Kazantsev (1658–1717), and is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.